Pilion: Where the Centaurs Roamed

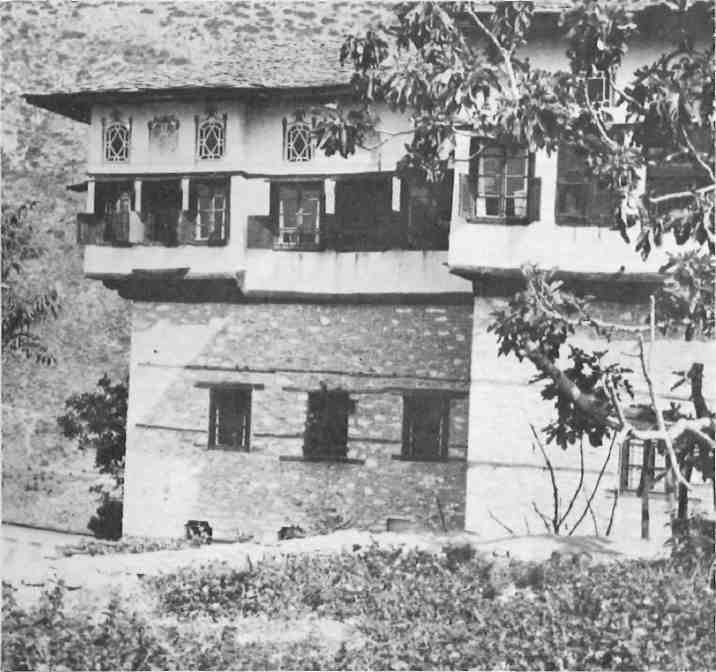

Covering most of the peninsula of Thessalian Magnesia, which juts out from the eastern coast of mainland Greece about half-way between Athens and Thessaloniki, is the Pilion area, dotted with villages strung out along the beaches.