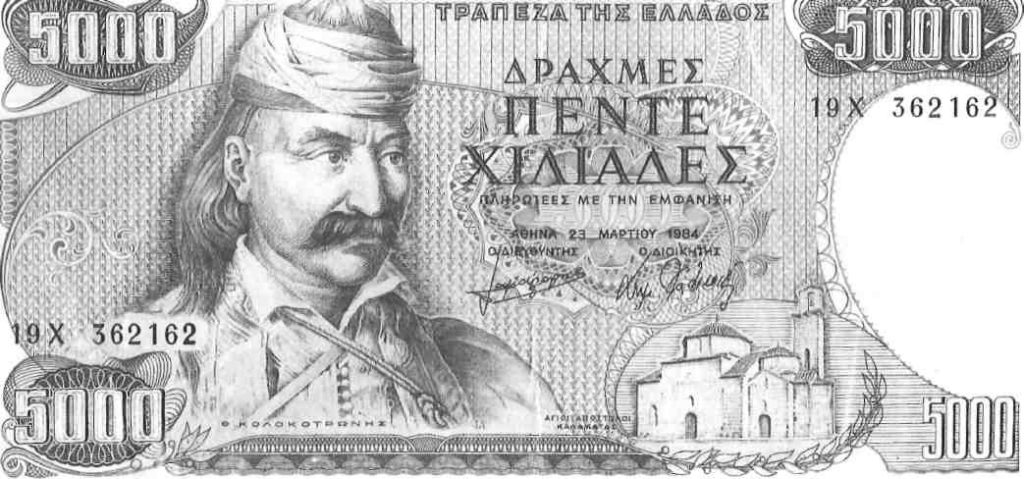

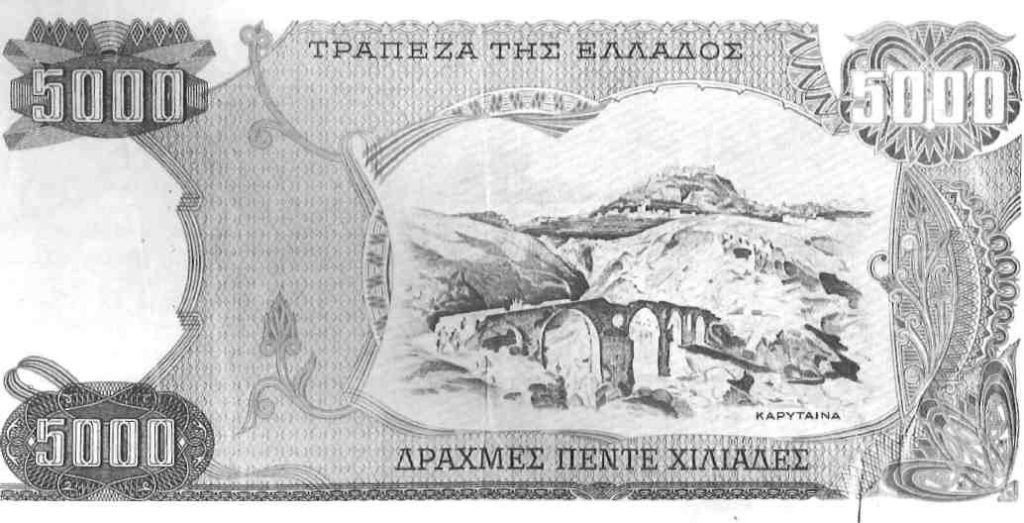

On the face of the 5000-drachma note blue-tinged Theodore Kolokotronis, War of Independence hero mustachioed and tur-baned, gazes out proudly over the country’s largest cash transactions. On the back of the bill the town of Karytaina with the Prankish castle of Karytaina looms over the medieval bridge which still spans river Alpheios. The engraving seems to be taken from an old print. Colloquially, the banknote throughout Greece is called a ‘Kolokotronis’ in honor of the Old Man of the Morea whose life was so involved with Karytaina and the area around it.

The likeness of the engraving to its appearance today when approached from Megalopolis is striking, and its geographical similarity to El Greco’s adopted town in Castilla has earned it the paratsoukli “The Toledo of Greece”.

The Kolokotronis clan, klephts of high standing, lived among the Arcadian highlands about Karytaina and made the castle their headquarters during the Revolutionary War, but, it was built over half a millennium earlier by a soldier of fortune from Champagne who had joined the Fourth Crusade.

Hugues de Bruyeres chose the ancient site of Brenthe to defend the defile of the Alpheios as it descended from the mountains into the valley that leads out to the Ionian Sea. The Alpheios river valley was crucial to the princely domain of Achaia ruled over by the Villehardouins, serving as a link connecting their capital of Andravida in the northwest with the eastern parts of the Morea.

Hugues married the daughter of his liege, Prince Geoffrey I de Villehar-douin, and their son, Geoffrey de Bruyeres, married in turn the daughter of Guy de la Roche, later Duke of Athens. Despite these favorable alliances, de Bruyeres was the loser in a quarrel in which he sided with his father-in-law against his uncle William, who had inherited the principality. As punishment for breaking his oath of allegiance to his sovereign, Geoffrey lost the right of original conquest, meaning he could not pass on his baronial fief to an heir of his house, but rather, only to an heir of his loins. This spelt the end of his family’s hold on Karytaina since Geoffrey de Bruyeres could not father a child.

After the death of his widow and Prince William, this key mountain for-tress was held entirely by the latter’s daughter, and the Franks lost the castle for good, when, in 1320, it was sold to the Greek emperor Andronikos Π Palaiologos.

Like most inland Frankish castles of the Morea, Karytaina largely vanishes from history for the next 400 years struggled over by Slavs, Albanians, Venetians, Turks, as well as Greek armatoli and klephts. After all these centuries of silence, it is interesting to first hear of Karytaina from the autobiography of Kolokotronis in terms of his having been an armatolos there.

The armatoli were armed Christians employed by the Turkish government to guard communication routes. Recognizing they could never control the Greeks of the mountains from Macedonia to the Peloponnese, the Turks had established the armatoli in 1534.

A century later, however, fearful of the strength which the armatoli had achieved, the Turks abolished the corps, tore down their forts and sta-tions, and put Turkish officials in their place. The armatoli were furious. They banded together and ‘stole’ back what was theirs, both historically and under the Turks. This is when these warriors of the hills first received the name ‘klephts’. Although the armatoli were reinstated, the klephts remained, now called ‘the wild-klephts’ who reject ev-erything to do with the Turks. Many, however, through subsequent centuries saw the advantage of being both armatoli as well as klephts. Theodore Kolokotronis, shrewdly, became one of these.

During the first days of the Revolution of 1821, many battles were fought in the area of Karytaina. In his autobiography, Kolokotronis wrote in his klephtic way, “Karytaina, from the commencement of the siege until the fall of Tripolitsa, gave out from the flocks of those who were well-to-do in the district, 48,000 animals.” Throughout his story, Karytaina and the people of Karytaina are shown to have played a large role in the liberation of Greece.

From November of 1826 through the winter months of 1827 the Old Fort’, as it was referred to in the early 19th century, was rebuilt under the direction of Kolokotronis’ son, Gennaios. It became a bulwark of strength in the Peloponnese and was one of the main reasons why Ibrahim Pasha’s monstrous exploits of killing and enslavement and his infamous attempt to destroy all vegetation in the Morea didn’t succeed in extinguishing the Greeks’ hope to create an autonomous state.

While the castle was being rebuilt, Kolokotronis writes, “they found some helmets that belonged to the Crusaders.” This interesting detail arouses curiosity why this old warrior found it worth mentioning it in his life’s story. Perhaps, as a gallant klepht of the mountains, he felt an affinity with the legendary Frankish knight with whom the spirit of the klepht was imbued. Or, maybe, a metal helmet fitted and shaped for a 13th-century Frankish head made the western conquerors more real than their silent stone battlements. Then again, the discovery must have appealed to his love of the warrior’s headgear, for although he wears a turbaned cap in the Hanfstaengl print on the bank note, he obviously preferred the horsehair pummel of the ancient helmet which he wears in his equestrian statue in front of the Old Parliament.

After the Revolution, Kolokotronis offered Otto, the new king, his fortress of Karytaina. “I said in my address,” he wrote regarding his offer, “that I had built the fort to be useful in any necessities of my country, but now, as I require it no longer, I wished him to accept it… I received a gracious answer that he would keep my building… As far as I could, I had always done my duty to my country, and not only myself, but all my family… I now saw my country free. I saw that which I, my father, my grandfather, my whole race, as well as all the Greeks, had so long desired.”

Perched on the side of the mountain, the red-roofed town of Karytaina falls in the afternoon shadow of its castle-topped summit. Below, the Alpheios follows its deep, narrow bed around the sentinel mountain. Prickly pears line the road snaking up to the main square from where all castle-searching adventurers must leave their cars. Shod in comfortable, thick-soled shoes they proceed to enjoy the wonders of Karytaina on foot.

As we follow the signs directing the way up through picturesquely dilapidated old buildings to Frourion above, the quiet of the medieval setting which covers the hill settles on the climber with a sense of timelessness and peace.

An obelisk along the path commemorates the men who fought for the castle on March 27, 1821, just six days after the official raising of the flag that declared the beginning of the War of Independence.

A few metres farther on, a bust of Theodore Kolokotronis surveys much of the land he fought so hard to free. Continuing straight on, beyond the sign directing the way left to the castle, we come at what had been Kolokotronis’ home.

Bits and pieces of stones precariously lie on one another, w.eeds grow out of what was once the floor, and a rusty, weatherbeaten sign that may have been Kolokotronis’ own doorplate is all that remains.

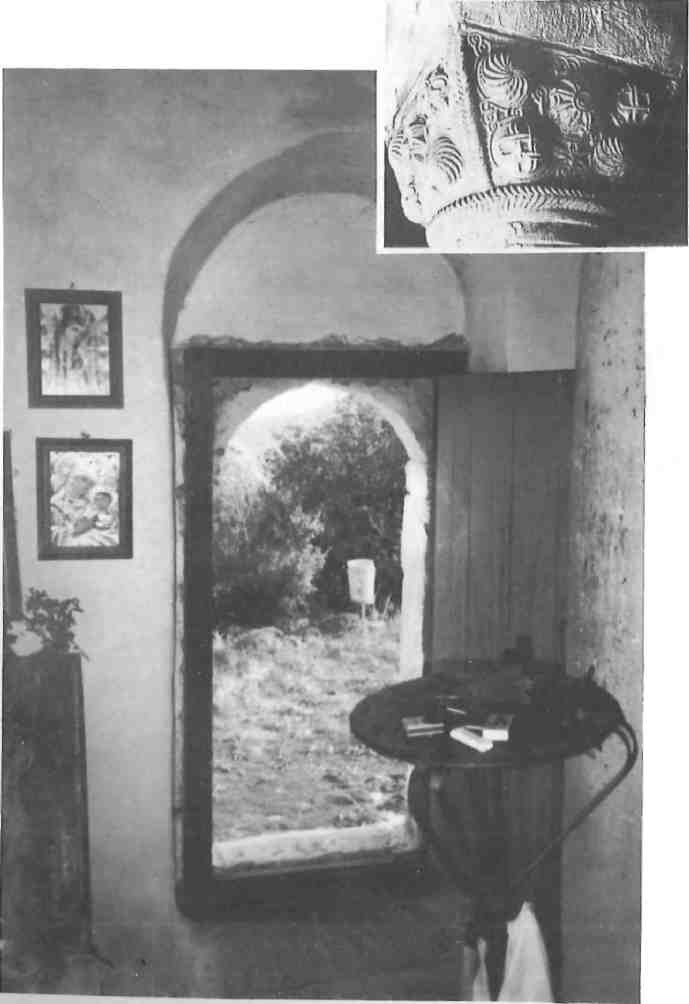

But across from it, the little stone church of Panagia tou Kastrou dating from the Turkish period is well worth investigating. The simplicity of its design and its careful upkeep tells of a much-loved place of devotion. Most likely, it was a favorite spot of Kolokotronis, for he strongly believed that it was in keeping with God’s will to liberate the country which had been amongst the first to worship ‘the Unknown God’.

The capitals on the chapel’s two columns are decorated with five bosses on each side in three different motifs. They date from the 11th century and are reused from an unknown church of earlier construction. The Museum in Izmir, curiously, houses the only other comparable type.

Retracing our steps a short distance, we turn at the sign directing the way to the castle and climb the rest of the path to the arched entrance situated in the east curtain. Mood-evoking, three stone corbels in the roof of the portal have us easily envisioning how missiles must have been showered down from the machi-colations above upon assailants storming the gate below, and we are thankful to be 20th-century tourists. The long-vaulted passageway leading into the courtyard of the castle rises sharply. Through the wooden frame that now adds support to the old walls, dark chambers can be seen.

The ruins of the castle are intermingled with weeds, bushes and a few small trees that are scattered around the triangular keep. To the left, the sun-bleached baronial hall still boasts some of its walls and four royally arched windows, and to the right, a broken tower stretches up. A good part of the rampart still exists with stairs that climb the side of the walls.

Arched, vaulted cisterns built beneath the central hall are impressive. However, the beauty of this watch tower castle is not to be found in its few scattering remains, but rather, in the location that man, from the ancient days of Brenthe, through the medieval days of the Franks, to the revolutionary ones of Kolokotronis, down to the recent days of World War II Germans, found so strategically placed that they all claimed its summit as the key to controlling the region.

The view is panoramic. The plain of Megalopolis is spread out like a fine woolen blanket to the boundaries of the mountains of Messinia and Lakonia, and the shaved mountains of Arkadia and Ellas’, arrayed a bit like chessmen on a board, stand to the back and sides of the fortress.

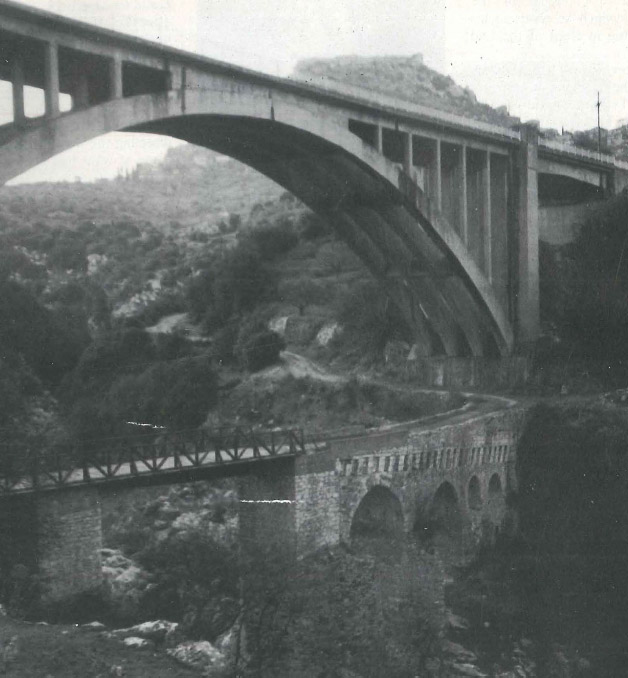

Perfectly aligned in the sight of the arched gate leading out of the castle is the Frankish bridge. Renovated in 1439 and used until recently by vehicles, it sits, useful still to the sheep and goats of Karytaina, directly under the modern concrete span constructed above it.

It is a postcard view of perfection looking onto fairyland. Even the smoke from DEH’s Megalopolis electricity plant that floats up from behind the hills seems to be the breath of a fire-eating dragon. The dragon must, of course, be fought and tamed by nothing else but a knight in shining armor. In fact, this land was anything but a fairyland during most of its history. It was too wealthy and strategically located to be left in peace by those greedy for gain and thus it suffered.

Today, it comes closer to being a land of magical charm than ever before. As the church in the square below rings out its .call to Sunday mass, we retrace our footsteps down the historic hill where thistles sing in the wind. We are glad to have experienced Karytaina – to have been one to walk the heights together with those of other times.