Co-AUTHOR: JOHN HARALAMBOS LEWIS

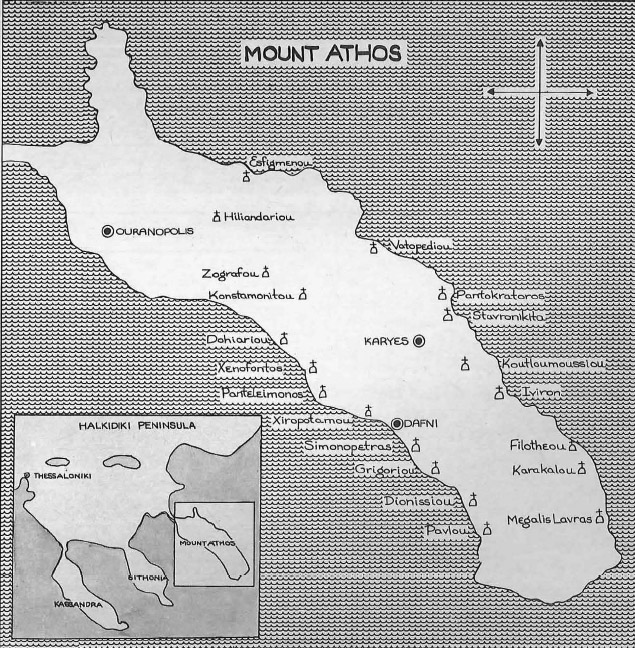

From Thessaloniki, a four hour bus trip through mountain villages and grove after grove of chestnut, walnut, and pine, brought us to Ouranopolis, the last secular outpost on the perimeter of the Holy Territory. Here we boarded the boat for Daphni, the only port town on Mount Athos. Rising like a steep pyramid on the easternmost prong of the Halkidiki peninsula, forty miles in length, its width varying from four to seven miles, the Holy Mountain reaches out like a talon into the Aegean Sea which is rarely out of sight from its lushly-wooded slopes. At a height of more than six thousand feet, its summit is visible from the slopes of Mount Olympus in the west, and from the coast of Turkey in the east.

In ancient times. Mount Athos was considered sacred to Zeus. That in 492 B.C. a Persian fleet on one of many expeditions against Greece was destroyed trying to round the cape, may well have been regarded by the ancients as divine justice administered by the Olympian god. A decade later, when King Xerxes led yet another Persian force against the Greeks, he took the precaution of building a canal (traces of it can still be seen) through the peninsula. In early Christian times, religious hermits sought seclusion in its remote, wooded forests, and monastic settlements soon followed. By the sixteenth century there were forty monasteries and Athos was a major centre of the Orthodox faith. One of the most beautiful sites in this area of the world, its monasteries richly endowed and with revenues from vast domains in Asia Minor, Russia, and the Balkans, Athos flourished as a centre of religion, learning, and art. The churches and refectories were covered with priceless frescoes and icons, the libraries over-flowed with unique manuscripts, the treasuries with religious relics from all over Christendom.

Athos remained the spiritual centre of Orthodoxy even after the capture of Thessaloniki in 1430 and the fall of Constantinople in 1453. Indeed, during the centuries of the Turkish presence in Greece, it flourished and retained its autonomy. Since 1926, Mount Athos has been part of Greece, but retains autonomy over administrative matters. Its constitution dates from 1783. Spiritually under the Patriarchate of Constantinople, it is governed by a Synod or Holy Council made up of twenty monks, each elected from one of the existing monasteries, and a representative of the Greek Ministry of Foreign Affairs.

To visit the Holy Mountain, one requires a special permit. For several days in Athens we had been obliged to run back and forth between various offices and the Ministry of Foreign Affairs to secure the necessary documents. (Later, the Abbots of many monasteries would express concern about the daily crowds of tourists that did not allow the monks to devote enough time to God, and often made them feel like “animals in a zoo”.)

Most visitors to Athos spend only a brief time there, some just a few hours, often arriving by yacht to tour one of the monastic settlements near the shores. There are few roads, and transportation is by foot, mule, donkey, horse, or the small boats that ply the seas around the peninsula, picking up or depositing monks or visitors at the various monasteries along the route. There is no electricity, although one or two monasteries have their own generators. Visitors are guests of the monks, sharing their frugal meals. With few exceptions, our meals consisted of lentils, bread, and wine, since it was a period of fasting. But then, periods of fasting are virtually continuous on the Holy Mountain.

In the eleventh century, the Byzantine Emperor, Constantine IX, decreed that “any woman, eunuch, beardless person, female animal, or child”, was forbidden on Athos. Female domestic animals and beardless men are permit-ted today, but females of the human species continue to be forbidden, despite occasional attempts by some to enter the area disguised as men and half-hearted efforts by figures such as Melina Mercouri to alter the regulation. For the moment, the closest view of the Holy Mountain permitted to women is from the sea — at a distance of two hundred metres from the shore.

At Daphni, Stelios and his bus — the bus of Athos as far as we could discern — were waiting. An hour later we were in Karyes, the capital, located in the centre of the peninsula, and the Territory’s only town other than Daphni. We presented our documents and a modest fee to the elderly clerk of the Holy Community. Tall and stately, he was clothed in the black cassock adorned with the Byzantine Eagle, worn by all the lay officials. After examining our documents and taking our passports, he issued us residence permits. We had officially entered the Holy Territory.

Karyes is a small dilapidated village, its major feature the fourth century church where the Holy Synod meets. There are two inns; a few restaurants; a plethora of shops, run by monks, which carry religious items, maps, canteens, and postcards; four grocery stores; a hospital; a post office; a tourist police station; and a communications centre with a single, ancient, hand cranked telephone. To modernize the telephone system would mean bringing in electricity, it was pointed out, and that might lead in time to the introduction of other electrical paraphernalia such as radios and television which would interfere with the contemplative life. We ate our first meal of lentils, and supplied ourselves with tinned goods, fruit, and a few essentials for the days when we would be hiking.

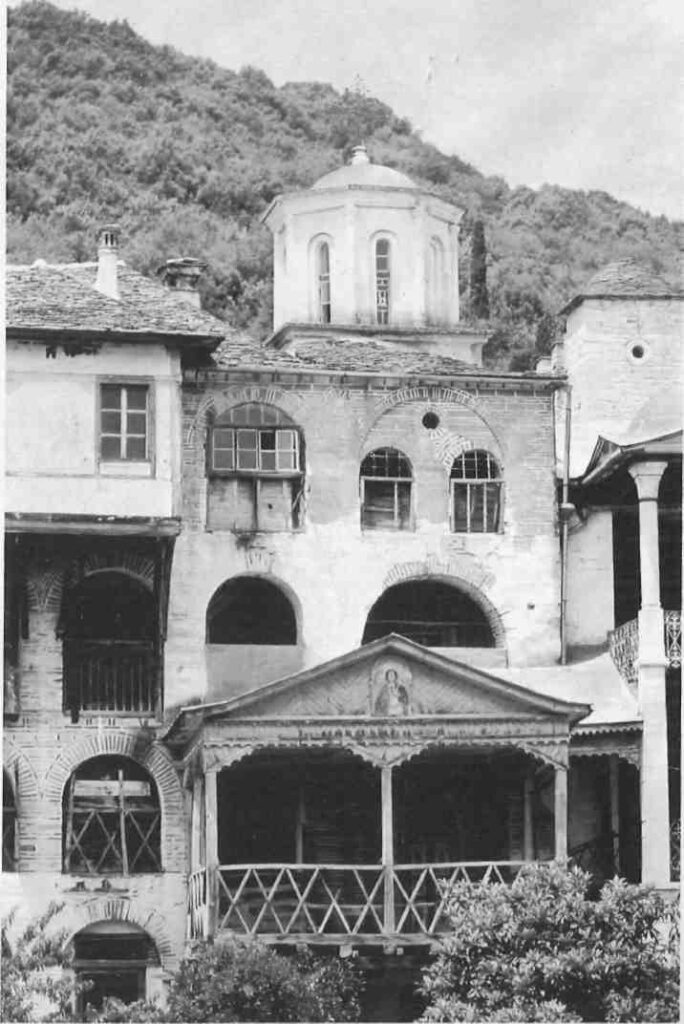

Today there are twenty monasteries on Mount Athos, ranging from modest settlements to immense, formidable fortresses that once accommodated hundreds of monks. Each monastery consists of a complex of buildings with several chapels and churches. Located by the sea, Iviron, the tenth century monastery noted for its unusual treasures, and the fifteenth century Stavronikita, are easily accessible by bus and usually receive more guests than they can accommodate. After a brief visit at Stavronikita, we began the long hike to Pantokratoros, further along the coast. En route, we met Farther Timotheos, a parish priest on pilgrimage to Mount Athos. A wealth of information, he was to accompany us for several days. An hour later, we emerged from the woods and saw Pantokratoros towering before us so close to the shore that it seemed to rise out of the sea. We were greeted by the Abbot and presented with the traditional welcome at all monasteries: loukoumi (Turkish delight) and tsipouro, a harsh, ouzo-like liquor, and led to the refectory where we joined a group of German tourists. The meal over, we were shown to a spartan, medieval room furnished with a table and six beds. Father Timotheos went off to services. Exhausted after our day’s travelling, we decided to go for a swim before beginning our tour, and made our way down to the shore.

Upon our return, an elderly monk stood eyeing us grimly as we approached. “May we visit the famous icon of the Panagia Gerontissa?” we asked. “No,” came the terse reply. “She left when she saw that you went swimming before visiting her.” We had yet to tune in to the monks’ sensibilities. It was some time before he relented and led us through the feeble light of the chapel, and into the Catholicon, the main church. Patiently and reverently he lit the candles one by one, each casting a new shadow, gradually illuminating the century-old frescoes that covered every inch of wall space, every niche, and the entire dome. To the left of the prie-dieu we saw the Virgin Mary standing life-size before us. Byzantine icons generally represent figures from the waist up but the Panagia Gerontissa (“The Abbotess”) is shown in full, her figure dazzling with finely worked silver and gold and precious stones which overlay the icon’s surface. The monk recounted the many feats and miracles attributed to her, among the most recent in 1950 when the monastery caught fire: the monks, he said, had carried the icon out of the church chanting the liturgy and as the Virgin advanced, the fire withdrew.

We awoke early the next morning to take the boat to Vatopediou Monastery. Boat-landing areas on Athos are often small ports, with now-abandoned living quarters and storage areas or “customs houses”, and turreted watch towers. It is not unusual to see logs piled high on the jetties since some of the monasteries deal in timber, a major source of income. The caique pulled in and we took our place beside several monks clutching plastic shopping bags containing the few items they would need on their journey. As the caique passed close to shore, tiny cells (skites) built into the cliffs came into view.

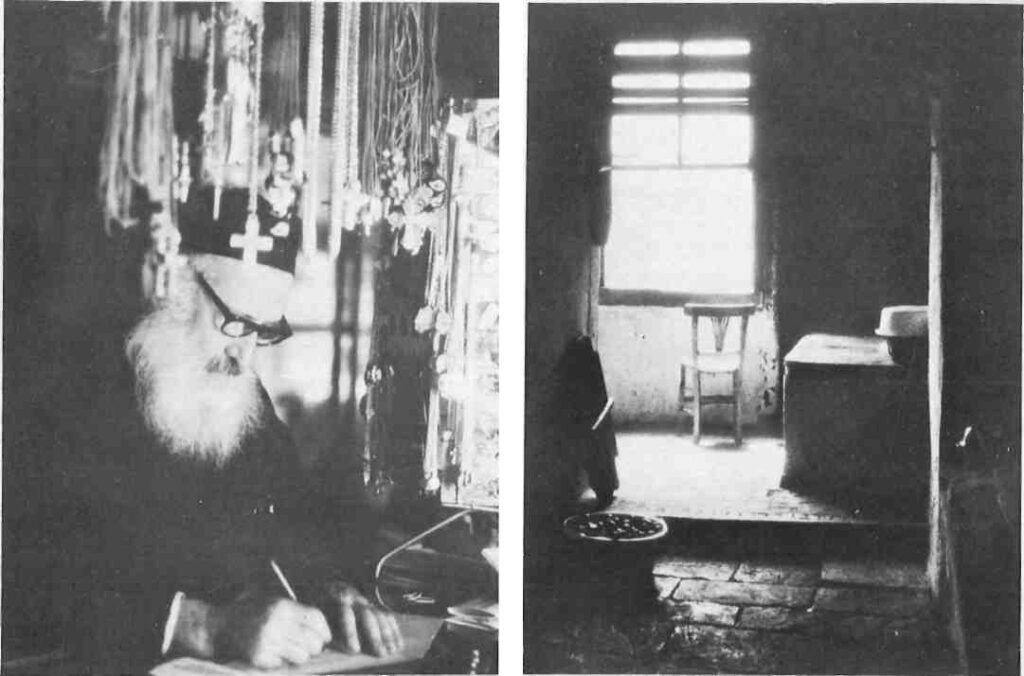

There are countless such skites throughout Athos, the retreats of the most ascetic monks, or anchorites. Most are now deserted, and the monastic life concentrated in the two existing types of monastery: idiorrhythmic, andcoenobitic. In the first, the monks live separately, usually preparing their own meals and eating alone in their cells which are often actual rooms or small apartments. At the coenobitic monasteries, the monks live a communal life, taking turns at the day-to-day tasks and eating together in the refectory. Although the number of monks on Athos dropped to less than two thousand in 1971, it is now said to be increasing.

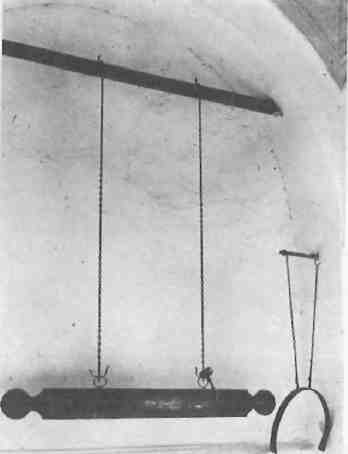

The time, on Mount Athos, is Byzantine — approximately three hours ahead of local Standard Time. The day thus begins in what is the middle of the night — around four o’clock in the rest of Greece — and comes to an end at sunset, when the monasteries close their gates, signaled by the beating of the simandron, a long piece of wood struck by a mallet. It is also used to call the monks to meals and to communal prayers. “You must be careful,” Father Timotheos warned us, “not to interfere with the monk’s schedules.”

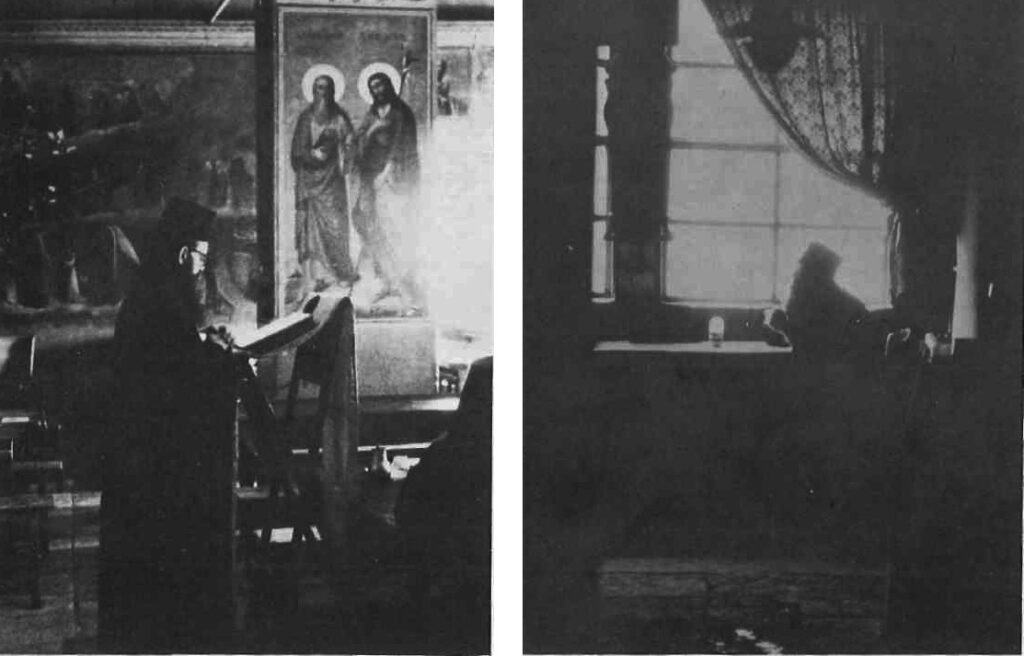

The monks begin their devotions with matins at four a.m., followed by mass from seven to nine. In the communal monasteries, they then breakfast in the dining hall after which they have “free time” to perform chores, with services at regular intervals throughout the day. Evening prayer is at four or five in the afternoon, followed by dinner, vespers, and vigils. By then, it may be going on midnight according to their time, and many retire to bed.

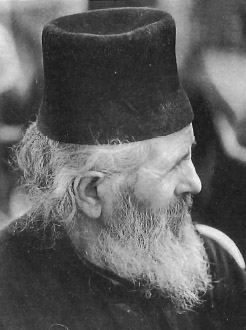

At Vatopediou, a vast monastery spread out over gently-sloping hills, and with beautifully-landscaped grounds, a young monk was assigned the task of guide. There is little resemblance in appearance between monks of the Western tradition and Orthodox monks, who wear a black habit not very different from that worn by Orthodox priests on ordinary occasions. Their hair is long, flowing freely or, more often, gathered up in a tiny bun, and beards are compulsory. Had our guide not chosen the Holy Orders, he might well have joined a track team. Seemingly incapable of a normal pace, he dashed about clutching his robe, and later was seen bustling about his chores. (As we panted behind, Father Timotheos noted that on the Holy Mountain it takes four hours to cover ten kilometres on foot, three hours by donkey, and two hours following a monk.) Although the monastery dates from the seventeenth century, it is the most modernized on the Mountain, its appearance sometimes likened by guide books to a country club. Of the many scholarly centres which once existed in Medieval times, that of Vatopediou was among the most renowned. The carefully-guarded library, the most outstanding on Athos, contains eight thousand volumes.

We had planned to set off before noon, but the monastery’s Abbot insisted we share their meal. We reached a compromise, agreeing to wait until the bread was out of the ovens, and he could see us off properly laden with freshly-baked bread, olives, cucumbers, and his blessings. We found the narrow, rocky footpath and began the hike north along zigzag paths, down steep hills, and across ravines, through snake- infested dim and silent forests, and swarms of insects. There were times when it seemed like a remote jungle. Arriving at monasteries, we were often greeted with mild astonishment by the fathers who told us that the trails we had taken had lot been used in years.

All of the monasteries on Mount Athos are Greek, except for Hiliandariou, which is Serbian, Panteleimonos, which is Russian, and Zografou, which is Bulgarian. Founded in 1197, Hiliandariou means “one thousand men” and it was built to house more than that number, although today there are only a score of monks. Situated in a well-irrigated, heavily-wooded vale, it is equipped with an electrical generator and farm machinery — gifts, according to the monks, from Marshal Tito. We spent the night here. Throughout the day, silently and incessantly, the monks repeat to themselves their Spiritual Prayer: “Lord Jesus Christ, Son of God, have mercy on me the sinner.” “I work all day with those words on my mind,” said a ninety-year-old Father selling komboskinia, long, knotted-silk cords, similar to rosary beads. “They are the first words on my lips in the morning and the last at night.” Continuing, he spoke of his convictions, tears coming to his eyes whenever he uttered the word Panagia — the Virgin Mary. One of our group absentmindedly began eating an apple from his backpack. Suddenly the monk became agitated and began lecturing us on the evils of gluttony, but in a few moments his voice subsided, his eyes closed, and he began to weep, expressing his fears for the salvation of mankind. Remorsefully, we took our leave and began the two hour climb that would bring us to Zografou.

The young Bulgarian monk who was our guide at Zografou did not speak Greek but greeted us with, “Pele? Mohammed AH? Dal” and ran through the roster of most of the world’s major athletes and the entire Bulgarian National Soccer Team. Some of the younger monks had not been on the Holy Mountain long enough to rid themselves of worldly sentiments, Father Timotheos commented. Having shown us around the monastery founded in the tenth century by Slavic noblemen, the monk led us to the tomb of Saint Simeon and showed us the grapevine which is said to have miraculously sprouted from the grave. Its fruit is believed to produce fertility, and visitors to Athos often take it home to their wives.

The veneration of objects in any way connected with saints or, indeed, parts of their bodies, is a tradition accepted in both the Orthodox and Catholic religions. St. John Chrysostom referred frequently to relics of martyrs as a source of divine favour. St. Thomas Aquinas counseled that saints’ relics were “temples and organs of the Holy Spirit dwelling and operating in them… hence God himself fittingly honours such relics by working miracles at their presence”. Ecclesiastical guide books to Athos usually enumerate each monastery’s relics and some of the lists are quite substantial. They include what are purported to be various parts of Saint John the Baptist (a finger at Zografou, an arm and part of his brain at Dionissiou), the Virgin Mary’s girdle (at Vatopediou), the left hand of Mary Magdalene (at Simonopetras), to name a few. At Grigoriou, we were shown the tiny, gold-encased skull of Saint Kyriakos, the youngest Christian martyr. Often the relics are said by believers to give off a sweet odour — a sign of saintliness — or to be warm to the touch. The miraculous icon of Saint George at Zografou (which means “the painter”) is believed to have been self-executed, manifesting itself on an empty panel. Today it has a blemish — said to be the piece of a finger which adhered to the icon when it was touched by a sceptical bishop.

Father Timotheos decided to remain at Zografou. Cutting our way west to the coastline, we set off for Dohiariou, where we were met by Father Pahomios who chided us somewhat harshly for taking photographs. A gentle, kind man, he later apologized and explained the reason for his concern. Monasteries cannot easily turn away Greek Orthodox males who proclaim their intention to become monks and occasionally criminals will seek refuge on the Holy Mountain. At the moment, there was one on the premises. Although the police were expected, Father Pahomios was fearful that our cameras would alarm the unwelcome guest. We assured Father Pahomios that we would not venture near the criminal’s quarters.

Another reason for his anxiety was the expected visit on the following day of a large contingent of military officers. Father Pahomios had already begun preparations, and food was simmering in immense copper pots set on top of a wood stove. The next morning we helped him slice the bread, and set places for sixty officers. When they arrived, Father Pahomios was in attendance, greeting them with dignity and selling tourist items, while we served the tsipouro and loukoumia. Some of the officers made their way into the kitchen for a quick first serving. In the midst of this confusion a group of tourists arrived, and Father Pahomios anxiously divided his attentions between both groups as the tourists began to bicker over their purchases, noisily pushing and shoving. When we took our leave some hours later, we felt somewhat depressed, but Father Pahomios thanked us for our help. It lifted our spirits a little.

At the “Russian monastery” of Panteleimonos we were met by a Serbian monk who had recently transferred from the Monastery of Hiliandariou (“a sign of instability of character”, Father Timotheos had told us, even though monks are free to move from one monastery to another), and the disconcertingly affectionate monk who insisted we join him in his quarters for confession. Our conversation was interrupted by loud screams from one of our group who began wildly slapping at his arm. The monk calmly plucked an insidious insect which was delivering a painful bite to our friend’s arm, and demonstrated how to deal with the pests, a constant source of annoyance, flourishing as they do in the lushness of Mount Athos. Holding it by the lower part of its body, the monk snapped off its head and threw its dismembered body to the ground.

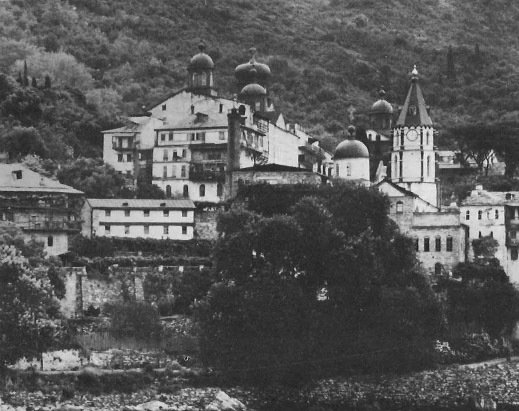

Panteleimonos, founded in 1169, is a huge monastery with a mixed history. Over the centuries, it received many monks from Russia, and its first Russian abbot, elected in 1875 at the request of the Patriarchate, was Archimandrite Makarios. At one time it was inhabited by more than two thousand monks. As with most monasteries on Athos, it was regularly ravaged by fire. In 1812, it was reconstructed in an elaborate Russian style, with gold crosses atop its many towers and gilded domes which gleam in the sunlight. Even today the monastery seems to carry echoes of the old Tsarist Empire. Bells peal at regular intervals throughout Mount Athos, but the bell-ringing at dusk on Panteleimonos is an astonishing sound and sight. In addition to the multiple small bells, there is a single huge one. From a distance, we watched in awe as one of the monks stepped under its immense girth. With only his feet visible to us, he began to ring it, the sound carrying, surely, for miles around.

The monks at Panteleimonos speak only Russian, but while exploring the monastery we met the Reverend Father Korzeniowski, a Russian Orthodox priest from England on pilgrimage to the Holy Mountain, who acted as our interpreter. Early the next morning we attended services at the Catholicon. Majestic and radiant in gold-embroidered vestments, Father Korzeniowski emerged from the altar to give us absolution. The service began. We sat alone in the immense and beautiful church, with row upon row of empty pews that in the past held thousands of monks, and reverberated with the magnificent choral singing for which the monastery was renowned in the Christian world. The fragrance of incense and the sheer beauty invited mystical images, bringing to mind the words of “Gentle Father Iosif” in The Brothers Karamazov: “…that is the belief in Athos, a great place, where the Orthodox doctrine has been preserved from of old, unbroken and in its great purity.”

Suddenly the church began to tremble. A distant rumble grew closer and closer as a horde of perhaps fifty tourists rushed into the church and pushed their way up to the altar, chattering among themselves. The chatter grew in volume with their exclamations of surprise that jean-clad, disheveled “tourists” were taking communion. Clearly we didn’t fit their image of pilgrims to the Holy Mountain.

We joined the monks at dinner for the last time at Grigoriou where we took our place at the refectory’s long rows of tables. The Abbot began a lengthy prayer of gratitude, then rang a bell for the meal to begin. It was Saturday night, the Sabbath, when the meals are somewhat more elaborate — in this case, a pasta prepared with squid — even during the strictest fasting. He rang the bell again for the wine to be poured and, finally, to indicate that the meal was at an end. During the intervals between bells, one of the brothers stood at the head of the room before a lectern, chanting from the Scriptures.

At Grigoriou and Simonopetras, where we spent our last night, the monks were noticeably younger and more erudite. Many speak several languages and have attended universities here and abroad. We sat up late into the night talking to a young monk who discussed philosophy and theology — Greek-born, he has a Ph.D. from an American university — and the next day made our way to Daphni.

On the boat to Ouranopolis, we began to think of the comforts awaiting us, of warm baths, soft beds, and rich meals. Then we remembered the; ancient, wrinkled father at Hiliandariou and his tears of concern for mankind. We knew that one day we would return to the Holy Mountain.