THERE is a fresh wind blowing at the Benaki Museum. This became evident in December with the opening of an exhibition on “Traditional Methods of Cultivation”. An exhibition that presents folk art as it finds expression in the tools and the paraphernalia of daily life is not unusual, but it was novel for Greece. There were none of the usual glass cases with objects unimaginatively placed next to each other. Instead one walked through an intricately-lit sequence of rooms, where agricultural tools were displayed on the walls or on the floor, grouped together according to their purpose. Photographic blow-ups made up the background, showing Greek peasants harvesting, threshing, and spinning. To even further enhance the display, traditional folk songs and instrumental music were played softly in the background. In June, another major exhibition on “Ancient Greek Art” opened: the N.P. Goulandris Collection of Cycladic and Protohistoric Art, which has attracted world-wide attention.

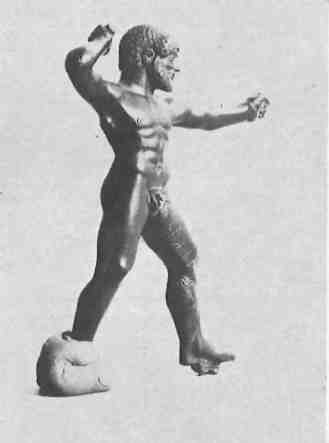

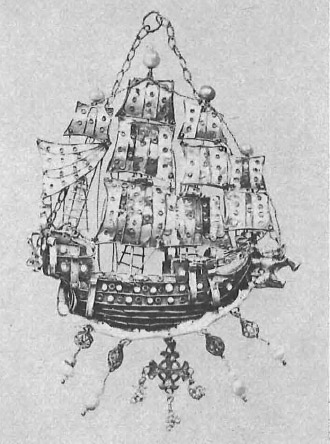

It was in 1931 that Antonios Benaki transformed his family home into a museum to house his vast and superb private collection of art, handicrafts, embroideries, swords, oriental faiences, jewelry, and ivories. Although this varied collection remains the nucleus of the Benaki Museum, it was early augmented by purchases and donations from other private collections and foundations. Among them were those of Antonios’s brother, Alexandros, and his sisters, Alexandra Choremi, Argini Salvagou, and Penelope Delta, as well as Mrs. Delta’s daughter, Virginia Zanas. Mrs. Choremi’s contribution included, in particular, vases and silver jewelry. Mrs. Salvagou, who lived in Alexandria, presented her fabulous collection of Persian jewelry. Friends added their contributions as well: George Eumorphopoulos donated Chinese pottery, and Diamanos Kyriazis, a fine collection of embroideries, pottery, drawings and water-colours. The Exchange of Populations Foundation donated religious treasures brought to Greece by refugees from Asia Minor in the 1920s, and the Eleftherios Venizelos Foundation added the great statesman’s files and memorabilia.

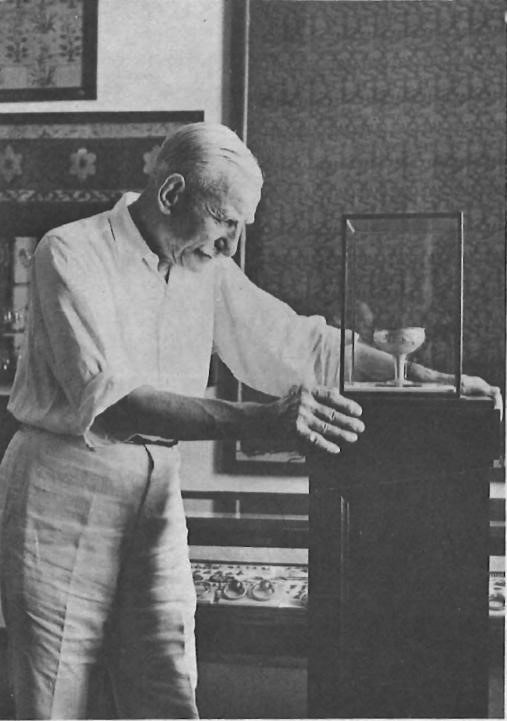

Despite the diversity of the collection, the emphasis of the Museum’s exhibits has always been to illustrate the wide variety of Greek art and handicrafts, from the Byzantine and post-Byzantine period, and to demonstrate the interaction with other cultures in this area of the world. Antonios Benaki, who remained active in the daily running of the Museum’s affairs until his death in 1955, could not have foreseen the major changes the Museum is now undergoing, but he would have approved.

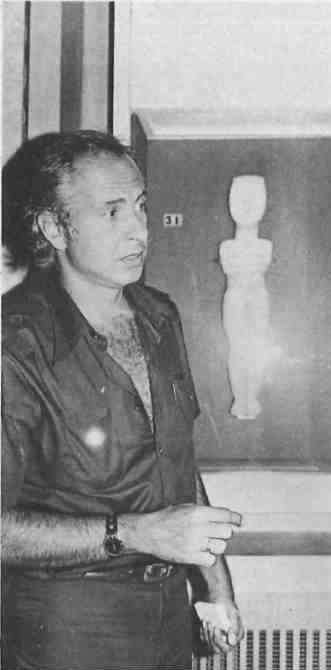

“A museum for the sole purpose of displaying a private collection, valuable as it may be, might have been a wonderful and appropriate institution in the Thirties. Today it is not sufficient,” says Dr. Angelos Delivorrias, the Museum’s director, sitting in his musty, spartan office. Today’s concept of a successful museum is to supplement the existing nucleus with exchanges from private collections and from other institutions, to demonstrate the evolution of style during certain periods, the influence of developments in art in other countries, and the interactions that occurred.

“We are trying to fill gaps in the collections, partly by rediscovering our own treasures in storage, but also by borrowing from others and extensively lending material to major exhibitions,” he continued. Among recent exhibitions abroad which included loans from the Benaki were “Late Antique and Early Christian Art” at the New York Metropolitan Museum of Art, “Four Hundred Years of Modern Greek Art” held in Belgium, and “Art of the Eastern Church” shown in Kloster Herzogenburg in Austria, which included thirty major pieces on loan from the Benaki collection. The 1976 Benaki show of “Byzantine Icons of Cyprus” was loaned by Cyprus.

“These cultural exchanges with other countries, either by assembling or participating in special exhibits, are of extreme importance in today’s world,” says Dr. Delivorrias, who was appointed to his post in 1973. “Today people travel a great deal more. Young people in particular are exposed to other cultures to such a degree that they want to learn more about them and understand better, beyond seeing individual pieces displayed in glass cases.”

A thorough reorganization of the Museum was begun by Antonios Benaki before his death. Experts in each field were brought in to document each section of the Museum’s collection. The result was the publication of catalogues on Byzantine manuscripts, the Chinese collection, and Ancient and Islamic glass. In 1948 and 1950 the Museum published To Lefkoma, two large folios of Greek folk costumes with paintings executed by the portrait artist Nicholas Sperling. Antonios Benaki also commissioned a more erudite work on Greek folk costumes which was compiled by Angheliki Hadjimichalis. The first of three large, profusely-illustrated volumes based on her manuscript is due to appear within a few months.

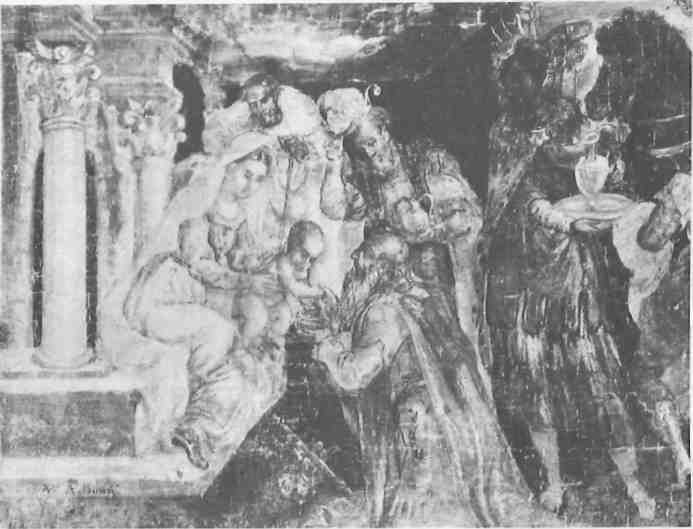

“In many instances we are rediscovering what we have.” Dr. Delivorrias said. “Some interpretations have to be reviewed in the light of newer studies and occasionally we make discoveries in our own storerooms.” Beneath a layer of gold on an icon undergoing restoration at the Museum’s restoration department, which is manned by two full-time specialists “and many volunteers”, a seventeenth-century icon was revealed. On the reverse side was an icon from the Palaeologian period (1384-1460) and underneath that, yet another earlier work.

Today the Benaki has a staff of approximately forty. Assistant to Dr. Delivorrias is Dr. Lila Maragou, Head of the Greek and Roman Art Section of the Museum, a specialist in ivories, and a full a professor at Ioannina University. Dr. Delivorrias and Dr. Maragou, both of whom earned their doctoral degrees at Tuebingen University in Germany, were recipients of the prestigious Humboldt Scholarship, which has been called “the Rolls Royce of scholarships”. Named after the eighteenth-century German naturalist and statesman, the scholarship is granted by the Alexander V. Humboldt Society, in cooperation with the German Government, to outstanding scholars from abroad for further studies in their fields. On the average, two hundred scholarships are given annually; since 1954 an unusually high number, one hundred and seventy, have been won by Greeks.

Mrs. Helen Philon heads the Islamic Section of the Museum. The substantial photographic archive, which is under the direction of Emilia Geroulanos, consists of some thirty-five thousand photographs. The main objective of these archives is to document all aspects of the Byzantine and post-Byzantine periods, from art and architecture to manuscripts and handicrafts. Many of these are not located in Greece. The Museum was recently assured of assistance from the Cultural Committee of the Council of Europe to further this aim and to develop the archives into a major centre for the study of Byzan-tinology and the post-Byzantine period.

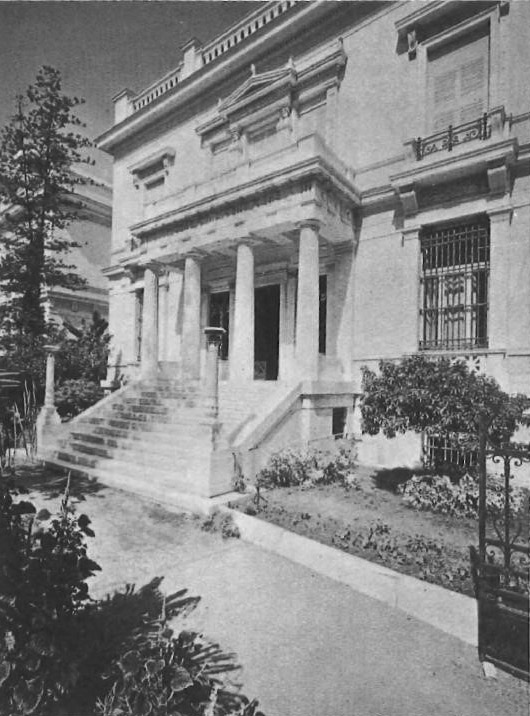

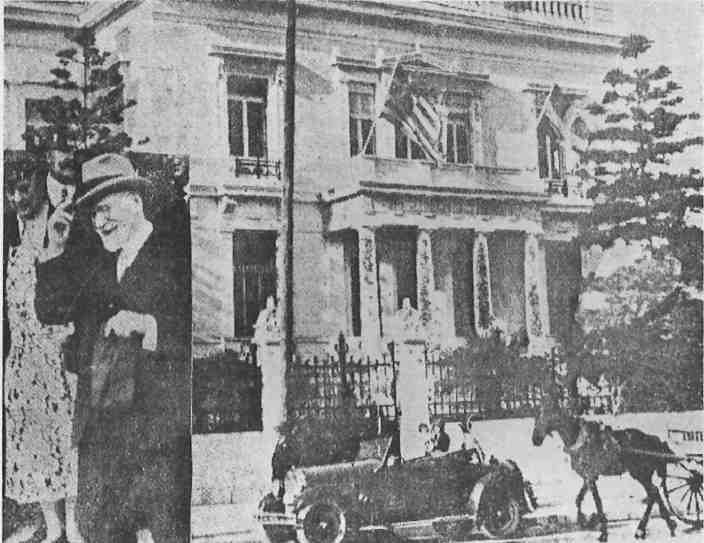

Benaki Museum on April 22, 1931.

In the Museum’s library, Kalliope Tsakona, the head librarian, has begun the gargantuan task of recataloguing some eighty thousand volumes, a labour expected to take another two years. With a heavy emphasis on the history of the period of the 1821 Greek War of Independence, and on folk art, the collection includes rare and in some cases unique manuscripts and books such as a dictionary printed in Venice in 1499, Inkunabulo Archetypo, or a 163 8 edition of the Bible printed in Geneva. Cataloguing is being coordinated with that of the Gennadius Library.

The Museum is organized as a private foundation and members of the Benaki family sit on the Governing Board of the Committee. Some of the running expenses are met by the Government but much of the income is derived from foundations and bequests made to the Museum, such as the large landholdings at Skinia Beach in Marathon, given to the Museum by Antonios’s second son, Konstantinos. (Antonios Benaki had two sons, Emmanuel, who was President of the Museum until his death in 1977, and Konstantinos, whose daughter, Mrs. Irini Kalligas, is Secretary of the Board of Trustees.). The ancestral home of the Benaki family, in Kalamata, is also a museum which the Archeological Services use to display finds excavated in the area. One floor is reserved for use by the Benaki Museum.

Emmanuel Benaki acquired great wealth as a cotton grower in Egypt and donated generously to many philanthropic institutions in Greece, such as hospitals, libraries, research foundations, and museums. Among his bequests were the Benakion Botanical Research Institute in Kifissia, and the Benakios Library in Athens. When Emmanuel moved his family back to Greece in the 1920s, he bought the turn-of-the-century mansion on Koubari Street as their residence. It was his oldest son Antonios who conceived the idea of the Museum and who spent several years and a considerable fortune to make the necessary alterations. In 1931, the Benaki museum opened to the public.

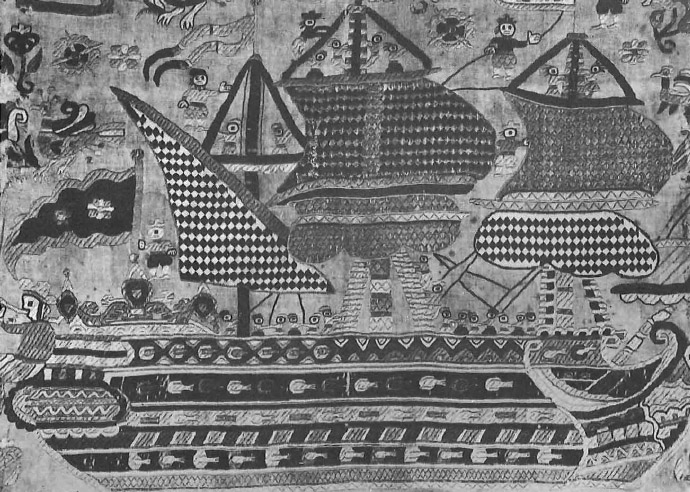

Today a priority is the reorganization of the existing material to demonstrate the historical development and continuity of culture in Greece as well as their interrelation with those of other societies: the documentation of not only the artistic legacy of the post-Byzantine period, but, for example, the daily, largely-agrarian life as it was led by the majority of the Greek people in the centuries after the fall of the Byzantine Empire in 1453.

A major obstacle is the lack of space. “The Museum is bursting at its seams,” Dr. Delivorrias says. There are plans to add a two-storey wing in the back of the Museum, where storage sheds are located at the moment. Hopefully this addition will begin soon, as it will double the existing space and also provide facilities for lecturing and research. The St. Dekozis-Vouros Foundation, a private foundation begun by the current President of the Board of Trustees, Lambros Eftaxias, has pledged funds for this extension and the Minister of Culture has given his wholehearted support.

The stress on Greece’s ancient inheritance led to the neglect of Byzantine and post-Byzantine studies. “Interest in medieval and modern Greece did not surface until the Thirties,” Dr. Delivorrias notes. The study of post-Byzantine art, he believes, is only now coming into its own. The next twenty years will show an increased interest in that period. “When this interest matures, the Benaki will be ready”.