VOTIVE offerings, found throughout the world and in all periods of history, are presented for a variety of reasons: the granting of a wish, the cure of an illness, the safe birth of a child, or for divine intercession in personal affairs or a catastrophe such as an automobile accident, a shipwreck or an earthquake. In return, an offering — a tama— is made to express — before or after the fact — thankfulness and devotion. As in other faiths, the offering in the Greek Orthodox tradition may take a non-material form: to repeat a prayer a certain number of times, to give up favourite pastimes, to abstain from sexual relations for a short period — or even forever. It may involve a promise to a particular church or shrine. (The Assumption of the Virgin Mary on August 15 is the occasion for thousands to pilgrimage to the Church of the Panagia Evangelistria on the island of Tinos, which houses a miraculous icon of the Virgin Mary; many of them will be fulfilling vows or seeking the aid of the Virgin Mary.)

Material offerings in the Greek Orthodox religion range from simple candles and vessels of olive oil, to valuable icons, rare works of art, and entire churches. There is, for example, the story about a caique which sprang a leak while at sea. The captain prayed to Agia Ekaterini, the patron of his church, asking for her intervention and promising to present a gold replica of his boat to the church in return for their safe passage. According to legend, the Saint responded favourably and a fish miraculously appeared and became caught in the hole, thus plugging the leak. The ship made it safely home, and the captain kept his promise.

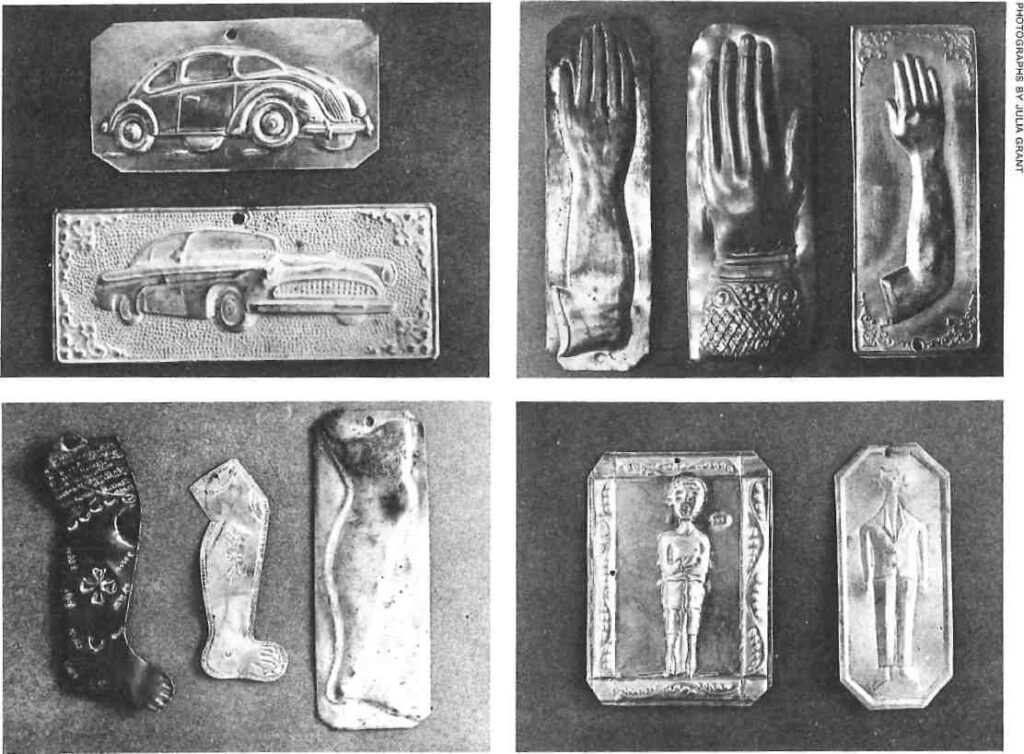

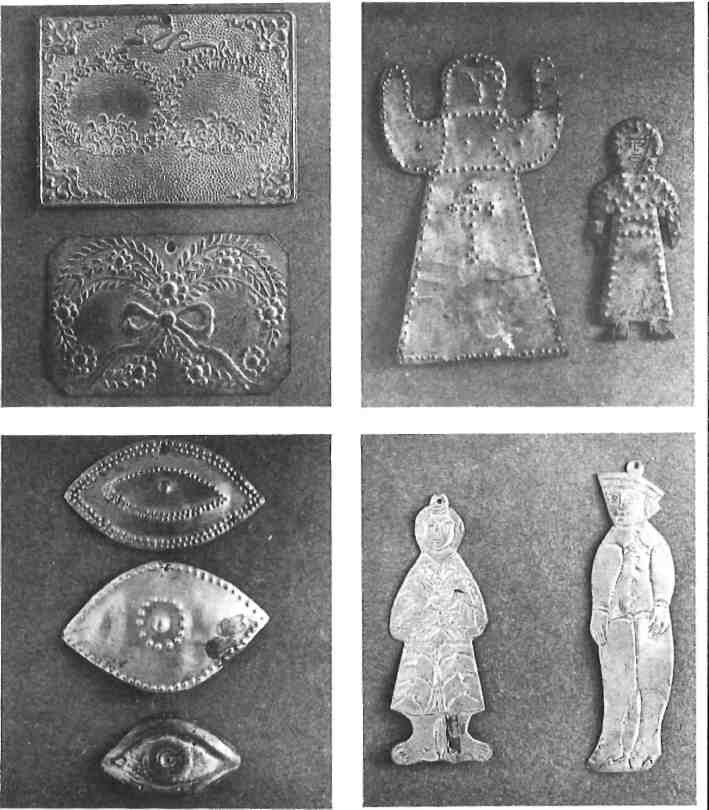

Anyone who has visited Greek Orthodox churches here or abroad will have seen one of the most popular types of tamata, the small metal plaques that are attached by ribbons to the iconostasis or tucked in the frames of icons. These tamata are pictorial representations of the favours asked for and can depict anything from babies, soldiers, boats, and cars, to various parts of the body in need of healing.

In Greece, the tradition of such votive offerings is an unbroken one, and can be traced back more than thirty-five hundred years. Archaeological excavations have yielded abundant evidence of such tamata from as early as the Bronze Age. The Ancient Medicine exhibit at the National Archaeological Museum displays examples in marble or terracotta, approximately twenty-five hundred years old, which were found in temples dedicated to Asclepius, the god of healing. By the fifth century A.D. the practice had been adapted to the Christian religion.

Although no longer made in marble or clay, the designs of these modern tamata are very similar to their ancient predecessors and those dedicated to Asclepius look little different from those dedicated to St. George or St. Nicholas. Just as the ancient Greeks believed that the gods were pleased by the receipt of votive offerings, so many Christians believe that similar dedications carry weight with the saints who may intercede on one’s behalf, strict theological interpretation not withstanding.

These tamata become the property of the church where they are dedicated. In the past, some were made of silver or gold and were ultimately melted down to be made into goblets or candelabra, wrought into covers or shields (many of which are still seen in churches today) for painted icons, or sold for their bullion value. Tamata could thus be an important source of income for a church and, indeed, in places such as the island of Tinos, contribute significantly to the economic welfare of the community whose members not only cater for the material needs of the pilgrims but to their demands for various votive offerings and religious souvenirs. Each year the Tinos Church auctions off the surplus tamata, allowing a donor to buy back a gift if it is an exceptional piece which the donor may wish to keep.

The presentation of such tamata may carry overtones of ecclesiastical commercialism, but they are nonetheless an outlet for spiritual expression that cannot be readily dismissed. These vows represent a contractual link, a significant relationship between the mortal and the divine. It is an arrangement that provides the believer with a feeling of security and an assurance that one’s individual lot will be looked after within the larger scheme of the universe.

Up until recently, all of these tamata were handmade by the donor or a local monk. They were rarely the work of a professional which accounts for the similarity and uniformity of design. People copied other tamata they had seen and admired, a practice that was not frowned upon. Copies were never exact, however, and the countless variations have thus produced a unique chronicle of Greek physiognomy and society. Tamata also reflect the changing times. The advance of medical science and popular knowledge about human anatomy, for example, have produced tamata of increasing anatomical accuracy. The Balkan Wars introduced new subjects (guns and swords) and today cars (to avert accidents) and diplomas (for divine intervention during exam periods) have appeared.

Interest in these plaque tamata as a folk art is very recent. They have been used or adapted in the works of such contemporary artists as Archelaos, Kavalieratos and Fassianos. Indeed, Alekos Fassianos has been collecting tamata for more than fifteen years.

Ironically many of the oldest and most beautiful tamata that exist today survived only because their maker was too poor to afford silver or gold and used plain ungalvanized zinc. Thus they escaped being melted down.

Custom-made tamata can still be ordered at religious shops or jewelry stores, but most of those available today are machine-made and chrome plated. These tamata hardly qualify as art, but can be charming because of their designs and their subject. From a purely practical standpoint, tamata make unusual gifts. Except for the old ones, which are now considered antiques, or those made of gold or silver, they are generally inexpensive. Although statistics indicate that the present generation is less devout than their ancestors, the custom of making such votive offerings is still widespread. They are thus likely to continue the spiritual, historical, and artistic link that has survived since ancient times.