Concern with the environment is no longer novel, but fifteen years ago it was. It was then that Angelos and Niki Goulandris became concerned about the fate of Greece’s rich flora and decided to do something about its preservation. The natural sciences had long been neglected in Greece. With few exceptions, zoology began and ended in the fourth century B.C. with Aristotle. In botany, the researches of Theophrastos, a pupil and collaborator of Aristotle, led to important contributions. In the second century A.D. Dioscorides identified six hundred plants and his system of plant classification and his book, Materia medica, remained the authoritative sources in both the East and the West for centuries. But a Dark Age lay between their contributions and the eighteenth century when naturalists from abroad, most of them travellers from England, resumed such studies.

When the Goulandris Natural History Museum in Kifissia opened to the public in 1974, few realized that ten years had been devoted to its preparation. The interval was a significant one and typifies the spirit that pervades the institution: a concept of perfection and a desire to do things right is apparent. The exhibitions may seem small in scale if compared to those of other, more-famous natural history museums, but great attention has been given to their quality.

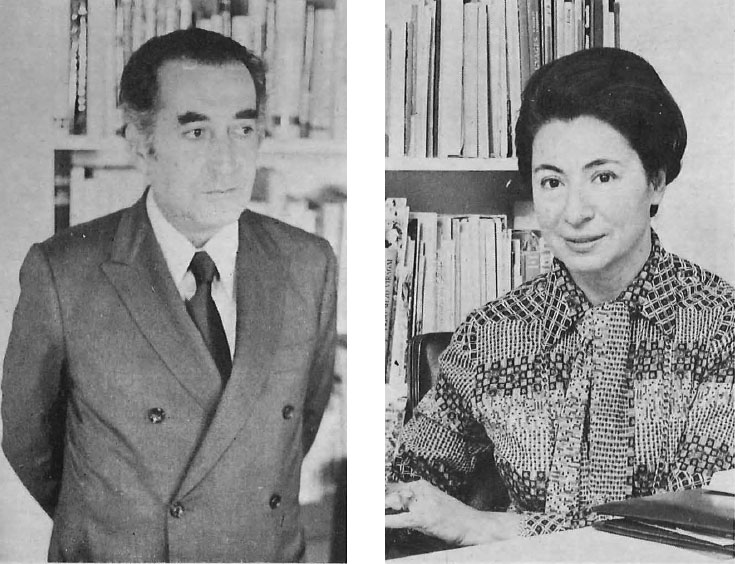

How does one begin to establish a museum? In the case of the Goulandrises, it was a private endeavour. Angelos and Niki Goulandris, both of whom studied political science, have always maintained many varied interests in the arts and sciences. (Niki Goulandris is an artist with a particular interest in flower painting, a challenging and highly intricate art in which she has won international acclaim. “This is the best thing I can do in life,” she says, showing me an exquisite watercolour of a crocus. It was in 1964 that Angelos Goulandris, concerned about the environment and wishing to foster a reverence for the gifts of nature, first conceived the idea of a museum of natural history which did not then exist in Greece. The university owned collections, but they were not open to the public. “The next ten years were the best,” says Niki Goulandris during a conversation in her book-lined office behind the Museum building. “We only collected.”

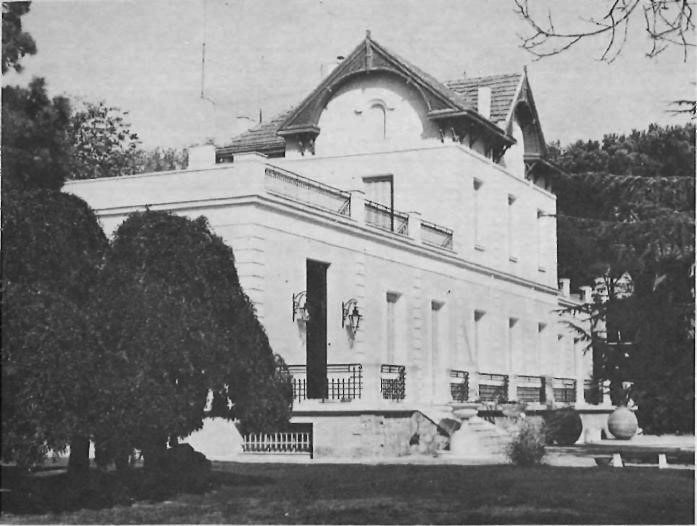

The Goulandrises assembled a small staff of scientists, advisers, collectors, and a designer, most of whom still work with them today. Greek and foreign botanists and naturalists were invited to participate in the preparation and extension of the collections. Complete private collections were acquired, either purchased by or donated to the Museum. Soon the work expanded into marine zoology, ornithology, entomology, palaeontology, and mineralogy. The search was begun for a large building, one that could house the collections and provide sufficient exhibition space. The former residence of the Retsina family on Levidou Street in Kifissia was bought in 1964, and after extensive restoration and remodelling of the handsome, spacious neo-classical building, it was opened to the public in 1974. The Museum’s aims are twofold: to provide a research centre for scientists specializing in the natural resources of Greece and the Mediterranean area, and to disseminate information.

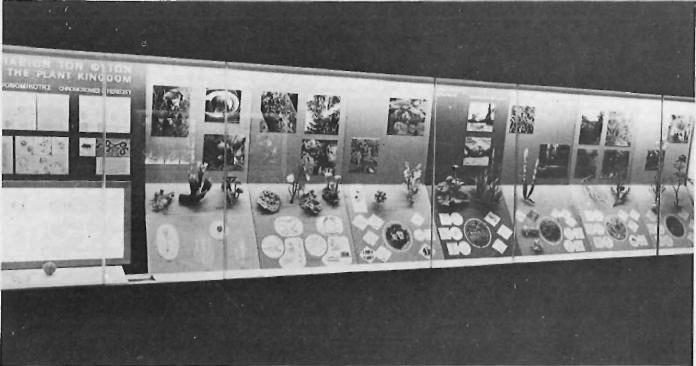

Most mornings the Museum’s grounds are dotted with blue-smocked school children and one is not surprised to learn that in 1977, out of more than twenty-six thousand visitors, almost twenty thousand were school children, The educational aims of the Museum are well illustrated by the first exhibit the visitor comes upon, the Botany Gallery. Panels on one wall of the long room illustrate the basic rhythm in plant life. Photosynthesis, growth, reproduction and heredity are explained with the help of meticulously executed drawings, photographs, and models of basic plant species.

Although the Botany Gallery was prepared in collaboration with specialists from the British Museum of Natural History (with whom strong links are maintained), all the other exhibits were designed and prepared locally. All are striking in their design: the Insect Gallery, with back lighted schematic drawings; the Mollusc Gallery, presented in two small rooms, with its intricately-lit, delicate shells on lucite stands. The descriptions, in Greek and English, are clear, a fact not to be taken lightly in local museums, where illustrations or legends, when they exist, are sometimes to be found taped or thumb-tacked to the walls. These and other details are largely due to attention to detail and constant supervision. Mrs. Goulandris recounts how, in their first publishing venture, they looked over the engravers’ work with a magnifying glass, checking on every line and shade.

Petros Zambelis, a graphic designer who has been associated with the Goulandrises for nearly twenty years, works with a staff of six when preparing exhibits. Their current major project is planning the galleries which will be housed in the new wing now under construction. The new facility will house the Museum’s entomological collection, and provide a more expanded area for the extensive collection of mollusks and the thirteen hundred stuffed birds in the ornithological collection. The various species of birds will be presented in dioramas reconstructing their natural habitat. The mineralogical and palaeontological collections, fairly recent additions to the Museum, will find their place in the new wing as well.

Although a variety of private collections, containing such things as plants, shells and minerals, were acquired over the years, systematic field surveys were undertaken by the Museum from the time of its inception. Today four members of the staff go on specific expeditions several times a year to collect specimens. The palaeontologist and the geologist on the staff (there are six scientists and their assistants working on a full-time basis at the Museum) do their own collecting. Elli Stamatiadou, a student of K.H. Rechinger, an Austrian botanist and specialist on Greek flora who was a visiting scholar to the Museum for many years, hikes over the mountains of the Greek mainland and the islands several times a year. At present efforts are being concentrated on border areas which have thus far hardly been explored botanically. The indispensable Alekos Pesiridis, a specialist in collecting sea plants, shells and minerals, is widely credited with possessing a “magic eye” for spotting specimens while just out walking. Aside from the four permanent collectors, there are contributing collectors residing in various parts of Greece.

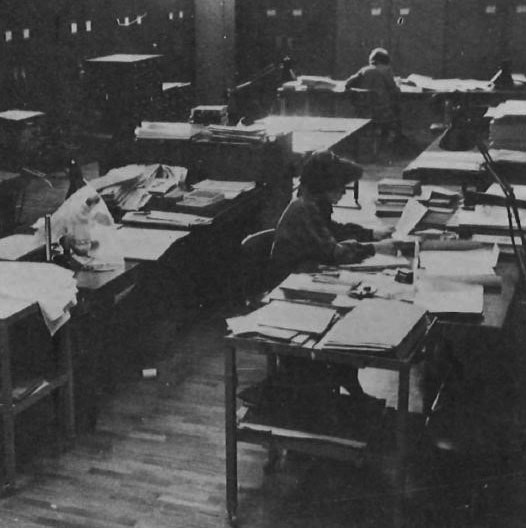

The Herbarium, located in the basement of the museum building, is the centre of scientific research. It has more than two hundred thousand specimens from Greece and the Eastern Mediterranean area catalogued by family,genus and species, with detailed information about their provenance. Preparatory work is now being done to introduce electronic data processing. Specimens are sent out in an extensive exchange program with other herbaria, primarily European, for scientific information.

Adjoining the Herbarium in the basement is the library. Aside from basic reference works, it contains a series of six hundred and fifty international scientific journals. There is also a modern laboratory where various experiments are conducted. As the Museum expands its collections into other fields, local and international specialists are invited to the Museum to work with its staff of scientists for several months of the year. Some of these collaborations have resulted in publications, an area where the Museum expects to expand still further. The Annales Musei Goulandris has appeared regularly since 1973. It includes scientific papers by members of the staff and visiting scholars, as well as outside contributions. In addition, the Museum has published two illustrated books: Wild Flowers of Greece, with text by the late Dr. Constantine Goulimis and illustrations by Niki Goulandris, and Orchids of Greece and Cyprus by Gerd Hermjakob, with colour photographs by the author, a German biologist who lived for eight years in Greece teaching at the Dorpfeld Gymnasium in Maroussi. The Flora of Mount Olympus by Arne Strid of the University of Copenhagen, with six hundred colour photographs, is now going to press and The Shells of the Greek Seas with approximately two hundred and fifty colour photographs, is being prepared. There are also plans for the publication of a periodical of natural history, in Greek, with a general readership in mind. Other plans include a regular lecture series and study trips for those with a more than casual interest in nature.

Up until now, the Museum has been privately financed. This has included the purchase of the building, the acquisition of collections, the salaries of the staff, and stipends for the scientists. Last year for the first time in the Museum’s history one fifth of its budget was met by a contribution from the Ministry of Education.

For Niki and Angelos Goulandris the Museum is an all-absorbing enterprise to which they have dedicated their lives. I found Angelos Goulandris busy coordinating various groups of visiting school children (I had actually mistaken him for a teacher). How many staff members does the Museum now have? “Twenty-five or so,” he replied, “plus the two of us, who work for ten.” Mrs. Goulandris credits her husband with the concept of the Museum and with “being able to see something in his mind in its finished form, organize it to perfection, and see it through to completion”. It is evident that they wish to remain in the background as they have done during their nearly fifteen years of dedicated work. The focus is on the Museum and the work being done there. They perceive their greatest contribution as having filled a gap and contributed to the awareness of a rich heritage about which little is known and which is endangered today. “How can you expect the young people to protect their environment when they know little of the functions of the plants and of the interrelations in nature? When plant names are hardly known, beyond garifala [carnations] and triantafila [roses]?” Mrs. Goulandris comments at the conclusion of our long discussion.

Not surprisingly the Museum’s guest book includes the most admiring comments from people known the world over for their contributions to natural sciences and conservation— from Jacques Cousteau to Dillon Ripley of the Smithsonian Institution, from the ornithologist Roger Peterson to Luc Hoffman of the World Wild Life Fund.