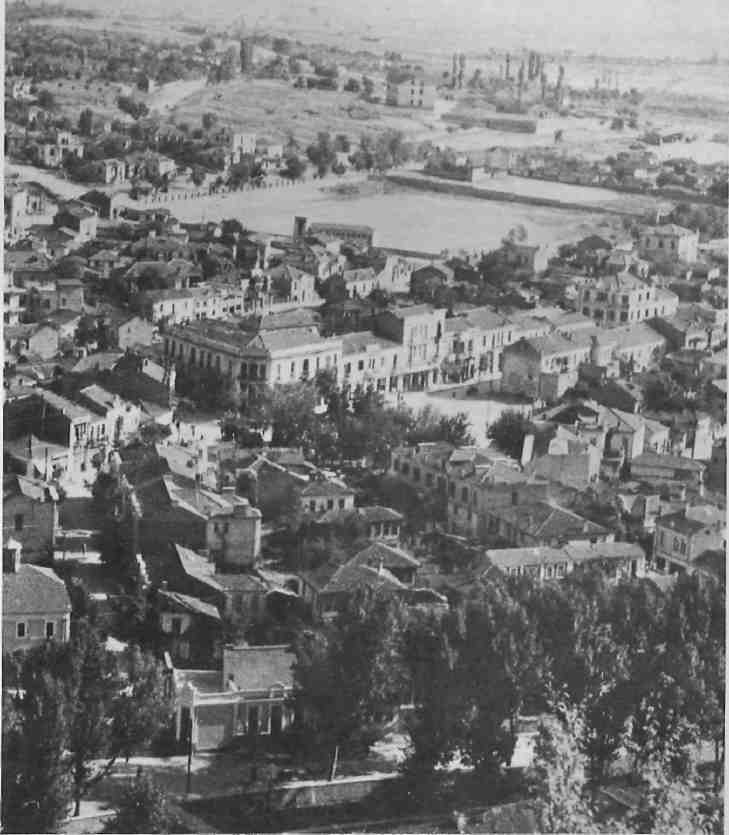

Nine miles south of Yugoslavia and fifteen miles east of Albania, Florina is nestled at the opening of an eight-mile valley enclosed by the oak and pine covered slopes of the Varnous mountain range. A white cross, twenty-four metres tall, looms above the trees on the southern peak facing east over a dusty plain dotted with patches of green grass and fluffy poplar trees. The cross, constructed in 1972 at the prompting of the Diocese’s ranking clergyman, Bishop Avgoustinos, is a conspicuous symbol of the role of religion in local affairs, and a subtle reminder of its cherished traditions.

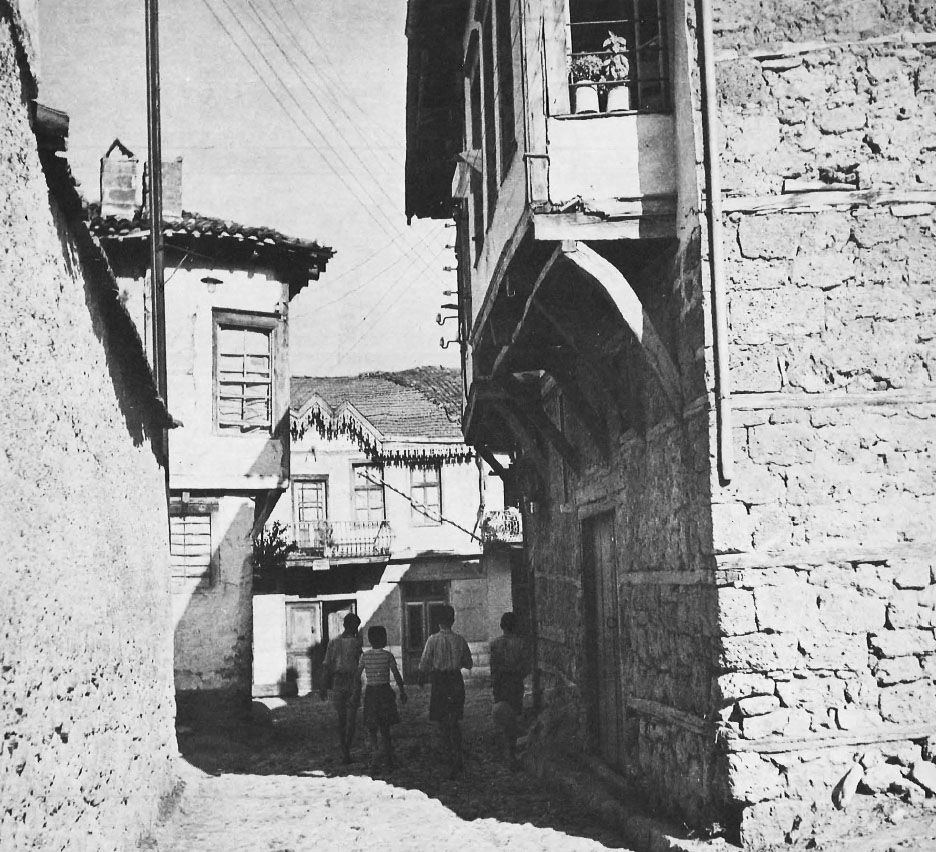

During the day, the valley echoes with the laughter of children at play, the pounding of construction workers’ hammers, and the crack of axes splitting wood. Multicolored buildings with long, narrow windows and faded red shingles swell onto the escarpments of the mountains, up to a few feet of the timberline. Narrow chimneys, capped with tent-like, tin covers to guard against rain and snow, lead down through sheet metal pipes to the cast iron stoves which are still used in ninety percent of the homes as the primary source of heating. Although the streets of Florina’s central business district are asphalt-covered, the residential roads are gravel or dirt. The men, dressed in baggy, tattered clothes and wearing dusty black berets, rattle down the thoroughfares in mule- or horse-drawn wooden carts. The carts, which serve as the town’s trucking system, carry everything from sixteen-kilo tins of olive oil to wood for stoves. Huge piles of tree limbs lie in front or along the sides of houses waiting to be sawed into smaller pieces. Roosters crow from perches on rock walls and cackling chickens scratch in the dirt roads for morsels of food. Old women, shrouded in black dresses, stockings, and scarves — seemingly in perpetual mourning — hobble across the gravel, bent under the weight of wicker baskets filled with the day’s groceries.

Florina’s main business district is two streets wide and ten streets long. In its centre, a rectangular area boxed in by concrete medians is set aside for the agora—the marketplace. Every Wednesday and Saturday local farmers bring their crops here, line them along the medians, and yell to passersby of the superior quality of their pure, unfertilized fruits and vegetables. Along Florina’s cement block sidewalks are narrow stores, restaurants and offices. One would not guess by looking at the paint-peeled and cracked walls, and the battered oak counters found in many of the shops, that F;orina’s economy is improving. Yet the four- and five-storey buildings which are gradually replacing the town’s predominantly old-style Greek architecture, indicate a construction and business boom which has sent local residents spinning.

The multiple-dwelling construction fervour began five years ago when Greeks who had emigrated to Germany and other European countries began to return, or when those who remained abroad began to buy summer houses in Florina. Another catalyst in recent years has been the improved trade relations with Yugoslavia. Now, several times a week, busloads of Yugoslavs depart from Bitola for the twenty-five mile trip to Florina. They flood the streets buying less-expensive Greek products, especially gold and silver. The rising middle-class merchants of Florina, billfolds bursting with drachmas, began to shun the half-century old houses of their parents for the modern conveniences of centrally-heated flats. Almost forty-five such multiple-dwellings have been built since 1972.

Such constructions have particular appeal to small landowners. In accordance with the practice universal in Greece, the contractor and property owner draw up an agreement of exchange — antiparohi— by which the contractor undertakes to build the dwelling. After completion, the owner is given the keys to his share, about thirty-five percent of the apartments. The builder keeps the remaining flats. Since an average two-hundred-and-forty-square-foot dwelling can fetch about $25,000, the landowner stands to make a considerable profit if he sells. If· he decides to rent instead, he has a guaranteed monthly income. The owner-builder percentage split has proved itself particularly beneficial to those who have inherited sizeable portions of land.

Despite the sweet smell of money in the air, a considerable number of the inhabitants are unenthusiastic about Florina’s future. ‘There aren’t any factories in Florina,’ says George Giannis, the owner of a small toy shop. ‘It’s basically an agricultural town — the farmers selling their wares to the merchants at the marketplace and the merchants selling their wares to the farmers at their stores. Now the continued growth of the town is linked to construction. There are about five hundred and fifty people directly or indirectly making their living off the construction business. When it stops, which it will have to in four or five years,’ he says, ‘there’s going to be a lot of jobless people.’

Fifty-three-year-old Giannis, who could weather a financial storm easier than most Florinians, emigrated to Melbourne, Australia in 1960, and saved ‘a bit of money’ working for the railroad. After ten years he came back to Greece, bought two stores in Thessaloniki which he now rents, and settled in Florina where he was born. Sitting in an armchair in the ninety-five-year-old house which his father owned before him, Giannis sips a warm glass of water, nursing an impacted tooth. He places the glass on the coffee table, and runs his hand across his silver, crewcut hair. The ensuing unemployment from an eventual construction halt is not the only unstable element in Florina’s economy which worries him. ‘The only reason for all our increased trade is that things are sometimes twice as expensive in Yugoslavia,1 he says. ‘Who can be sure this will go on forever? Maybe in two years it will be exactly the opposite and we’ll be doing all our buying in Bitola. Then the Yugoslavs will have the money. There’s no future in Florina. Business is hardly dead — yet. But it will be. And the people all know this.Our population has been dropping for twenty years.’

The exodus began most noticeably throughout rural Greece after the end of World War II. Constantinos Phillippa, a teacher at Florina’s Elementary Teachers Academy, says this migration was spurred by ‘young people eager for a better life’. Many left for other countries. ‘It’s all part of a trend,’ Phillippa says, as he surveys one woman’s tomatoes at the agora.Finding them unsatisfactory, he moves on. ‘In the late 1940s, the average population of a village was between five hundred and one thousand. Now, it’s mayoe three hundred.’ In 1947 the 1,863-square-kilometre district of Florina had a population of seventy-five thousand. Today, there are fifty thousand inhabitants. The city of Florina itself dropped from thirty thousand to around ten thousand. Migration to other countries is ebbing with this generation, Phillippa says, and being replaced by migration to larger Greek cities. The young are studying hard to enter universities in Athens and Thessaloniki, where they will remain after graduation. ‘The reason for the popularity of the big city is a simple one,’ says Phillippa, a short, muscular man, with coal-black hair showing traces of grey at the temples. ‘The young people don’t want to work in small towns. They prefer the opportunities and excitement of the larger cities. They are not satisfied with the simple lives of their parents and grandparents. The overall effect is that the Greek villages are dead or dying, particularly those in the mountains.’

Evidence of such a dead village can be found seven miles west of Florina in Vatohori, which is all but deserted. The windows of the low-walled houses are boarded shut and the streets are empty. Once a village of five hundred and fifty, Vatohori now has a population of sixty-five. Those who stay on, mostly the elderly, scratch an existence from the land and live in government-built brick apartments. An old man, riding side-saddle on a burro down the shoulder of the two-lane highway says, ‘They’ve all gone to Canada and America. They’re all gone now.’

So drastic a fate as that of Vatohori does not await Florina, town residents believe. Even if trade with Yugoslavia were to dry up and business were to blow away, the town would never be abandoned to such an extent. Florina, they are convinced, has the built-in safeguard of being deep-seated in modern Greek culture, and holds a special place in the hearts of countrymen because of its post-war history. According to Theodore Antoniou, a retired horse cart driver and sometime Florina history buff, his home town holds the distinction of having held back the Greek communist forces during the Civil War until Nationalist reinforcements could be mustered. ‘There are fifteen miles of Varnous mountains around the Florina area,’ says Antoniou. ‘The communists held the mountains for four or five years and we fought them there until we finally beat them in 1949.’ Staring off into space, as if reliving that period, when brother turned against brother and families were torn apart, Antoniou continues. ‘It was bad for Florina in those days. Every night you could see in the mountains little lines of light from the guns, like phosphorus.’

Antoniou, eighty and ‘some years’ no one is quite sure, including himself speaks of his town as one would of his country. ‘Let me tell you this also,’ he says, his eyes swelling with tears and his lower jaw set firmly accentuating deep wrinkles in his face. ‘If it weren’t for the courage of the people in Florina during the Civil War, the entire country would be communist today. Because if Florina had fallen, the communists would have been in Athens three days later,’ he says with more pride than accuracy. The wounds of that fratricidal struggle have yet to heal.

Sitting with an erect back at the kitchen table in his son-in-law’s house before a hearty meal of bread, pork and potatoes, Antoniou’s memory delves further into Florina’s past. No one is certain of the derivation of Florina’s name, but there is speculation. One tale is that shepherds found gold florins in the Lignos River which meanders through the south end of town. Others believe a Venetian adventurer named Flore founded the town. Florina’s modern history as a Greek town began, uncertainly, sixty-five years ago, during the 1912 Balkan War, in which Greece, Serbia and Bulgaria were allied against the Ottoman Empire. In the absence of conflicting claims between Serbia and Greece or any written agreements, it was accepted that the first soldiers to arrive in a town would have the right to claim it On the principle of effective occupation’. Florina was among the unclaimed towns. According to one apocryphal story, Greek soldiers, after liberating the town of Amindeon eighteen miles east of Florina, halted their forward march to celebrate their victories with the well-known local wine. A good deal into the festivities, a scout came to Amindeon to inform the soldiers of Florina’s undetermined status. Another scout went north to meet advancing Yugoslav forces and informed them that Florina had been taken by Greek troops. Thus, the Yugoslavs turned back. Some hours later, the Greek soldiers, dragging rifles in one hand and bottles of wine in the other, staggered merrily into the town to be greeted by the happy citizens. The population increased rapidly after its liberation, and Florina became the marketplace for the surrounding villages.

It was after World War II, when the young started migrating to the United States and Australia in large numbers, that Florina began experiencing hard times. ‘As more and more villagers left, the businessmen of Florina lost their customers. In the late 1950s and through the 1960s, when I was in Australia, most of the money which many of the townspeople had came from relatives working abroad,’ Giannis says. What started after the war continues today, and Florina loses its citizens and its village customers bit by bit, year by year. But, if the dwindling population makes Florinians dubious about remaining here, they hide it well. Of the twenty-five inhabitants to whom I spoke, none have plans to pull up stakes. All are certain that a depressed economy in the future will be checked by government intervention before any severe damage is done.

There are some nearby success stories from which the residents can take heart. Twenty-five miles southeast is the town of Ptolemais, the site of the biggest fertilizer factory in Greece. A village of two or three thousand two decades ago, it now has a population of over twenty thousand. Thirty miles south, jutting out into a lake, is the small, wealthy town of Kastoria. Once a poor fishing village, the townspeople changed all that when they discovered they had an amazing proclivity for weaving together tiny pieces of fur to make coats. Kastoria is now prosperous. Fifteen miles east, directly south of Amindeon, is Sour Water Village. Seven years ago, an entrepreneur from Athens came to the poor village, distinctive only for an abundance of mineral water with a peculiar, sour taste, and built a soft drink factory for lemonade and orange juice. The products provide the villagers with work and the man from Athens with a very profitable business.

Some are optimistic about Florina. The town’s new technical school will train craftsmen previously hard to find in northern and western Greece. Geological studies have indicated rich mineral deposits throughout the Florina area. Right now, only a small coal deposit is being exploited near Amindeon; it is manned by only a handful of men. New mines in the area would require a sizable work force.

If the Civil War helps to keep this remote area in the public eye, so does its Bishop. During national celebrations, there is at least one right-wing politician who calls for remembrance of those border towns which held off the communists in the last major battle, in 1949; and when the towns are named, Florina always heads the list. During the rest of the year, there is Avgoustinos, the Bishop of Florina, locally referred to by his family name, Kondiotis. Often the topic of light-hearted conversation, the Bishop frequently puts Florina on the front pages of newspapers quarreling over religious matters with other high-ranking church officials, or waging one of his frequent crusades. Locally, he is either loved or hated for several noteworthy performances: his baptism of a caravan of gypsies, after which he ordered that a suburb be built for them on the outskirts of town; his refusal to say mass before anyone wearing blue jeans; his vociferous campaigns against divorce, lewd films, or mixed swimming, are usually discussed with amusement. However, his almost single-handed campaign to have the unwanted $40,000 cross on the hill built is not so warmly treated. When asked about the cross, most residents wrench their mouths, shake their heads, and say ‘Kondiotis!’

Good or bad, it may be that the Bishop knows something everyone else does not. There is a chance that a well-publicized town will rank among the first to receive government aid or government-sponsored employment when problems begin. If such is the case, Florina has a jump on other towns. As Bishop Avgoustinos once modestly put it, ‘Two things make Florina popular with the Greek people. Florina lemonade and orange juice, and me.’ An unknown and possibly troubled future has had little effect on the life-style of its inhabitants. Year after year, days go by in the same leisurely fashion. On most days the shops close from one to five in the afternoon. The merchants, carrying clear plastic bags of groceries, return home, don their pajamas, and eat their main meal of the day, which always features large loaves of thick-crusted bread, freshly baked in one of the town bakeries. The meal is concluded with whatever fruit is in season. After the women clear the table, everyone retires for the mid-day siesta. The afternoon nap is still taken very seriously in Florina. All work ceases and those who choose to forego their rest, congregate quietly in the few restaurants and cafes which remain open, discussing politics in low voices or playing cards. Those who disturb the peace are treated harshly and slapped with fines of several hundred drachmas. When the shops reopen at five, the merchants file down the sidewalks, the flesh under their eyes still baggy from sleep, smiling and waving to one another. By the time the merchants lock their doors at eight or nine o’clock, people are already milling in the town square or walking arm-in-arm down Alexander the Great Street, which is closed to motor vehicles during the evening. The evening walk is as much a ritual to the Florinians as is cooking with olive oil. Even before the sun is completely hidden behind the mountains, women, groomed and dressed in ankle-length dresses, are on the street with their children. They meet their husbands and stroll, first down the’ street, and then back up again. As they walk, they greet their neighbours as if they had not seen them in years. Couples pushing baby carriages are the main attraction, as walls of people enclose the frightened, wide-eyed children. By nine or ten the pedestrian traffic on Alexander the Great Street begins to thin and the more affluent take seats at sidewalk cafes or at paper-covered tables in restaurants.

On Sundays and holidays, men don their suits and ties and women their best dresses to entertain friends and relatives with elaborate home-cooked meals. Others may wander aimlessly through the gently-rolling dirt paths in the zoo, located just west of town. In the late afternoon, young girls assemble on porch steps to discuss their favourite movie stars. The boys go to schoolyards to play basketball, or look for an empty field for soccer scrimmages against lot-drawn teams. The older people stay inside and watch sports programs on television, or attend a wedding or baptism. The Florinians are comfortable with their way of life and disdainful of the hectic life in the city. Whatever the future, there are many inhabitants who will refuse to leave as long as it is possible to exist here.

‘Of course we’ll stay,’ says Giannis. ‘This is our home. There’s no other place we would want to live.’ Says the wife of one of the town merchants, ‘If things go bad, we’ll stay. We were both born in Florina and our hearts are here. Somehow we would make do.’