Photographs courtesy οι the German Archaeological institute

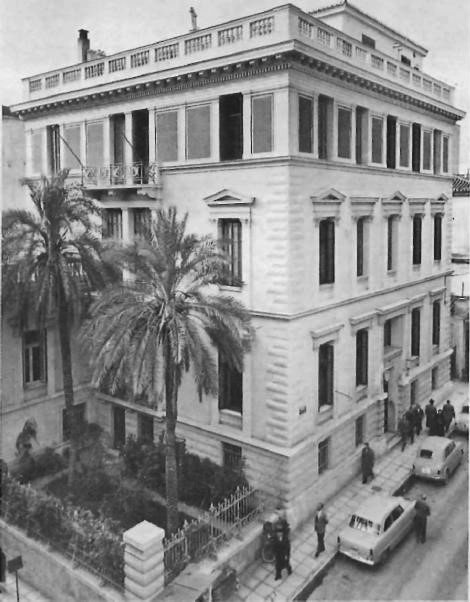

To enter the German Archaeological Institute today is to step into an unhurried, peaceful oasis from another era. The 1920s are the recent past, “since 75” means, quite naturally, 1875, and Schliemann and Doerpfeld are spoken of as if they were sitting in the next room. Scholars arrive for the first time when they are young men and women, and may devote the rest of their lives to a single task.

The German Archaeological Institute was not the first of its kind in Greece. The French School of Classical Studies came first, founded in 1846. The German Institute was officially established on December 9, 1874, the anniversary of the birth of Johann Joachim Winckelmann, the noted eighteenth-century classicist and historian. The American School was founded in 1882, the British in 1885 and the Austrian in 1898. The various schools share similar objectives, but each is distinct in form and organization.

The early morning sun streams through the high windows into the library. Beneath the painted, vaulted ceiling, a librarian perches on a well-worn ladder; a few students are reading at nearby tables. The bright rays of the sun, combined with the dim light of the reading lamps, create an eerie atmosphere. As I begin my research on the Institute’s history, I discover that the most recent book on the subject was published in 1929, on the occasion of the hundredth anniversary of the founding of the parent Institute which was celebrated in Berlin in the presence of such illustrious personalities as President Paul v. Hindenburg, State Secretary Otto Meissner, and Minister of Foreign Affairs, Gustav Stresemann.

The Institute in Athens was the first offspring of the central organization; there are now ten, dispersed throughout Europe and the Middle East. Their study projects have been diverse, ranging from work at the thirteenth-century palace of the Mongolian Prince Abaka Khan in Iran, to excavations of a Celtic town in Southern Bavaria, to the study of old inscriptions, numismatics, papyrology and historical topography. Although the exact date of the establishment of the Athens Institute can be pinpointed, its real beginnings gc back to Rome where, on April 21,1829, a group of intellectuals, poets, sculptors, archaeologists, and diplomats met at the Palazzo Caffarelli, the residence of the Prussian delegate to the Holy See, to establish a private organization which they named ‘Institute di Corrispondenza Archaeologica’. Its aim was the preservation of ancient monuments. Among those present were Barthold Niebuhr, a well-known historian, statesman and philologist, and successor to Wilhelm von Humboldt as Prussia’s ambassador to Rome, and a young archaeologist, Eduard Gerhard, who was to become the first director of the association. When Gerhard returned to Berlin a few years later to work with the Prussian state galleries, the administration of the Instituto di Corrispondenza Archaeologica moved with him. In 1870 the Prussian state, under whose aegis the institute was functioning, took over the administration and the financing. One of the few organizations surviving from the Kaiser’s era, it continues to retain a certain autonomy even today. The central administration, which is still located in Berlin, includes representatives from all German states whose universities teach archaeology. After 1837, when Gerhard moved to Berlin, Rome became the centre of field operations.

Some isolated work begun in Greece was supervised from there, with archaeologists making occasional field trips to Greece and to Asia Minor. Upon the death of a young scholar attached to the Prussian Embassy in Athens, the state bought a small scientific library from his estate and made it available to visiting scholars. The activities in Rome were oriented to culture and the atmosphere of that cosmopolitan city played an important role in academic circles: visiting scholars and artists came through and stayed. By contrast, Athens was more provincial. Field work was dispersed over the entire country and, as one chronicler put it, ‘the spade was more important than literary treatises’.

The Institute really came into its own in the latter part of the nineteenth century. Its history, and particularly that of its Athens branch, is laced with famous names in the field. The historian and archaeologist Ernst Curtius succeeded Gerhard. It is to Curtius’s decade-long perseverance that the German archaeological school owes its ‘allotment’ of the ancient site of Olympia. Hitherto Rome and Roman history had been in the foreground, but under Curtius the emphasis was shifted to ancient Greece. Other illustrious names are Richard Bohn, Adolf Furtwaengler (the father of the late conductor Wilhelm Furtwaengler and grandfather of a present member of the Institute, Andreas Furtwaengler) and, foremost, Wilhelm Doerpfeld, who, as a young man, was assistant in Olympia to Bohn, whom he later succeeded.

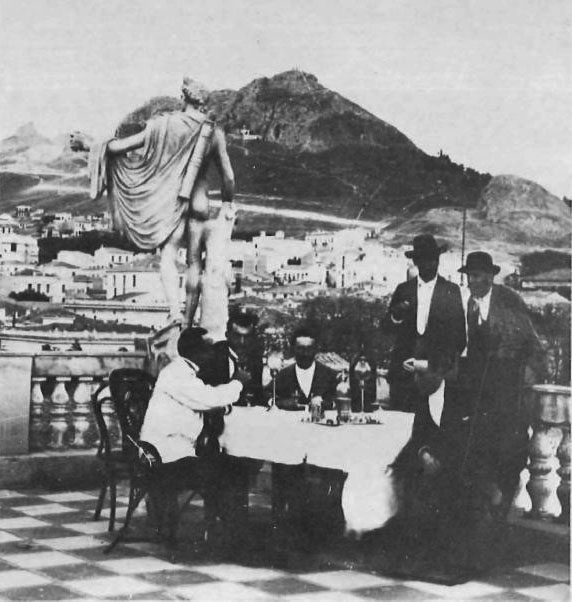

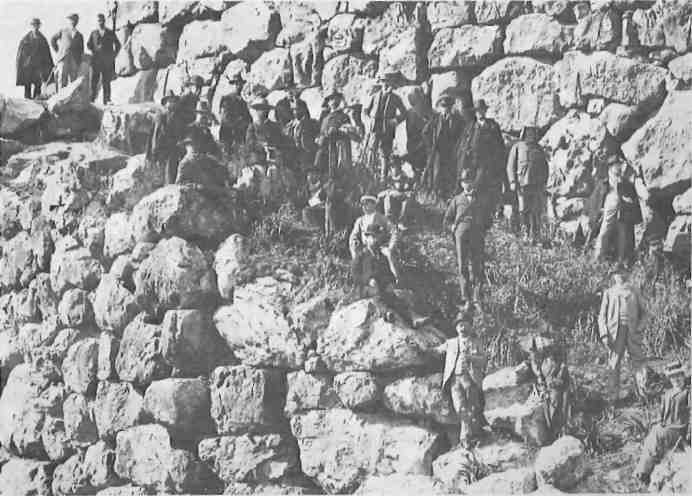

When, in the 1880s, excavations were halted in Olympia, Doerpfeld considered returning to Germany to pursue his career as an architect. He was persuaded to stay on at the Institute with the implicit understanding that he would spend the better part of his time aiding Schliemann who had privately begun to excavate in Mycenae and later in Tiryns. Doerpfeld, who was to be the Institute’s director for more than twenty-five years, closed a missing link today considered of primary importance in all excavations: the participation of architects in archaeological projects. Schliemann is said to have welcomed Doerpfeld’s cooperation. Although both were difficult men, the evidence suggests they got along well together. Doerpfeld remained in Greece for most of his life, raised his family here, and became co-founder of the German school (now named after him), where he also taught. His merit is uncontested although some of his theories, which he is said to have pursued at times with missionary zeal, have been disproven. Others were never taken seriously, among them his conviction that Odysseus’ Ithaca was, in reality, the Ionian island of Lefkas. He was so convinced of this that he retired to the island and started digging on his own. He died there in 1940 at the age of eighty-seven.

In its early years, the Athens Institute conducted few major excavations such as it has in this century. Instead, its efforts were directed to research and smaller projects, and to assigning archaeologists on its staff to other private excavations, such as Schliemann’s. Research is still one of the Institute’s main activities today. Gerhard Schmidt, the editor of the Athenische Mitteilungen a yearly volume of reports on work done in the field and other research projects, proudly points out that the publication, issued in only six hundred copies, has appeared regularly since 1876, the only interruption occurring during the Second World War. The library, with more than forty thousand volumes, is considered one of the best in its field and is said to be the ‘heart of the study of antiquity in Greece’. In addition, there is an exceptional photo library containing seventy-five thousand prints and negatives.

For many years now, excavations have been carried out by the foreign schools through permits granted by the Greek state. The maximum number of permits allowed per year to each school is three, although they may continue to work on other projects; once a school is involved with a project, it usually remains in its hands. The German Institute, which has been directed since 1975 by Helmut Kyrieleis, is currently working on four extensive projects: Olympia, Tiryns, the Kerameikos in Athens, and the Temple of Hera on Samos. All but the Samos project were begun in the last century and Olympia celebrated its centennary in 1974. The Institute’s involvement with these excavations and their funding are rather complicated. (Indeed, Olympia is independently funded by the Deutsche Forschungsgesellschaft, administered directly from Berlin, although its staff members are associated with the Institute.)

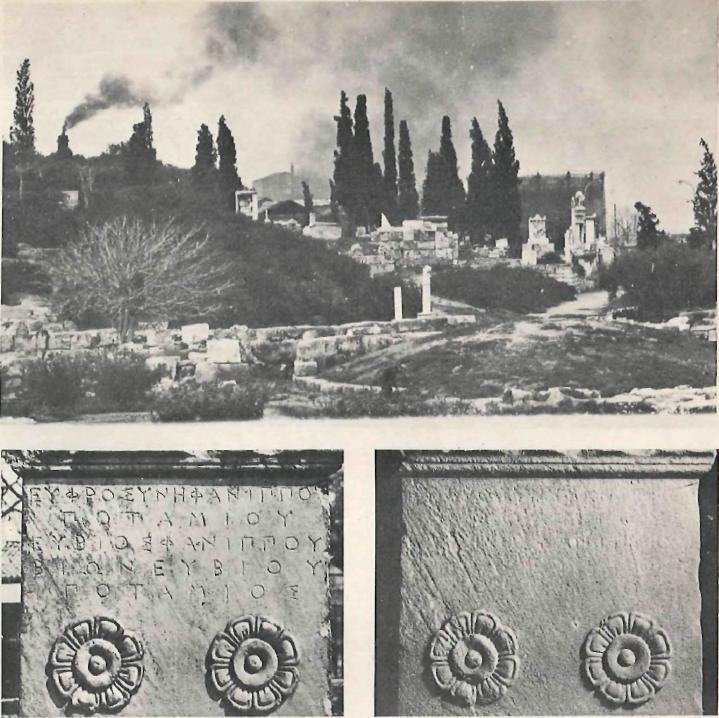

The Kerameikos, which was just outside the walls of ancient Athens, is today an idyllic area in the middle of a busy intersection at Pireaus and Hermou streets. Originally restricted to a small area of the ancient burial grounds, the Institute’s territory has twice been expanded to enlarge the field operations which are under the supervision of Ursula Knigge. Work at the Kerameikos was begun in 1870, and it has been in the hands of the German Institute since 1913; the present phase of excavations was begun in 1956. The site has proved to be a most fertile dig. Excavations brought to light part pf the ancient city wall with the remains of the Sacred and the Dipylon Gates, which played an important role in the ceremonial and religious life of ancient Athens. The Sacred Gate opened onto the Sacred Way to Elefsis. The Dipylon was the chief gateway of Athens; it was here that women, maidens and youths assembled for the Panathenian Procession to the Acropolis, a highlight of the annual festival in honour of the goddess Athena.

The Kerameikos is threatened by the same widely publicized pollution as the Acropolis, compounded by the presence of a nearby factory which was supposed to be shut down years ago but continues to pollute the surrounding area. Photographs taken over a period of two years reveal the gradual disappearance of the inscriptions on the burial steles. Furthermore, Ms. Knigge laments, the two roads bordering the cemetery, which are now congested with traffic, particularly buses and trucks, are being widened to accommodate more vehicles.

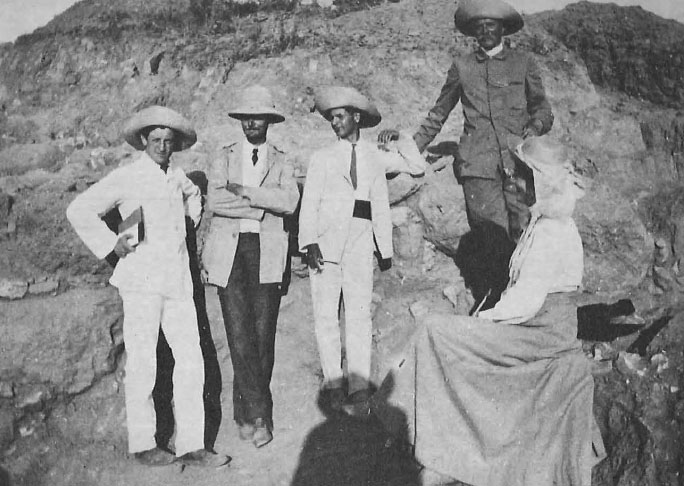

The Institute’s largest project is at the Mycenean site of Tiryns, a few miles north of Nafplion, where work is being carried out under the direction of Klaus Kilian. Begun by Schliemann in 1876, most of the major excavations were carried out in this century, despite interruptions during the war. The latest project was begun in 1968. Finds thus far suggest that there is still much to be done. It is assumed that the fortress was surrounded on all sides by a city which is still largely covered. One area of focus is the excavation of the massive walls surrounding the fortress which are yielding important clues about Mycenean technology and history.

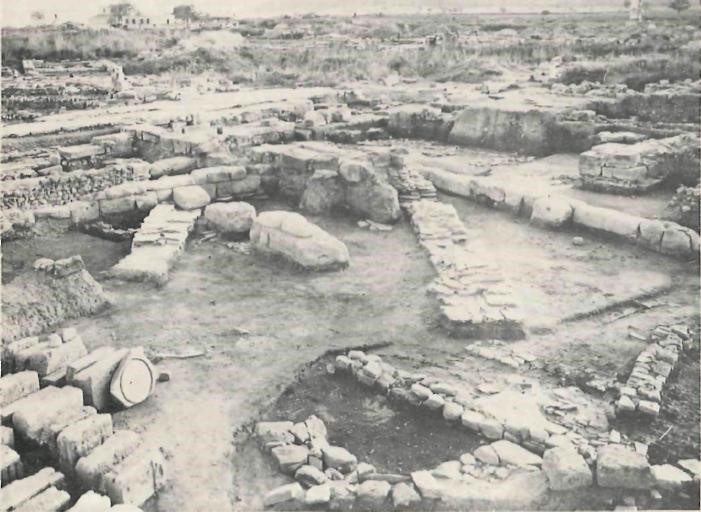

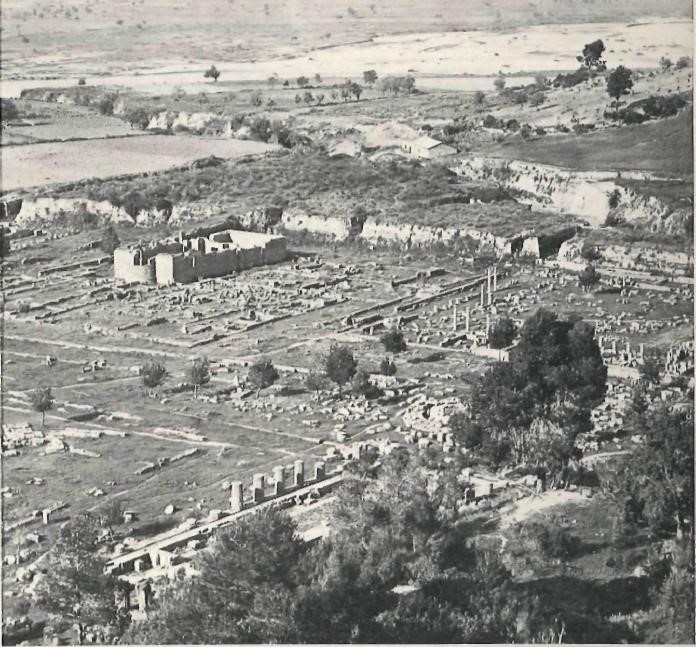

A sense of continuity and timelessness emerges even more strongly during discussions with Alfred Mallwitz, the director of the excavation of Olympia. An architect and the author of Olympia und seine Bauten, Mallwitz has spent more than twenty years working at Olympia and says, ‘There is still so much unanswered about it.’ Thus far there have been four major periods of excavation at Olympia. Doerpfeld originally assisted and later led the first from 1875 until 1881. In 1906 he returned to Olympia to concentrate on one small area, where, through more extensive excavations, he hoped to shed some light on the dating of the Temple of Hera, the oldest and best preserved building at Olympia. The third period of excavation began in 1937, with a significantly enlarged field of operation, under Emil Kunze, an authority on the geometric as well as the pre-historic periods of Greek History. He was the Institute’s director from 1951 until 1966. Officially launched on the occasion of the Olympic Games in Berlin, this project came to an end during the Second World War. The fourth period began in 1952, with Mallwitz as the staff architect, and ended in 1966. The next ten years were devoted to the evaluation, classification and publication of the rich finds. The fifth excavation, to be led by Mallwitz continuing the work begun by Kunze, is expected to start at the end of the year and to continue for an estimated five or six years.

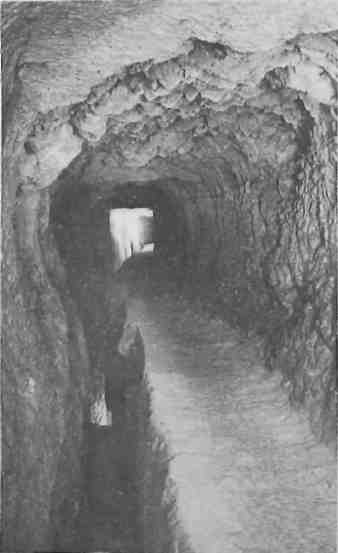

According to Mallwitz there is little doubt that there are enough unanswered questions about Olympia to occupy at least another generation of archaeologists. Among the unresolved issues are topographic problems such as the location of the agora and of the end of the Sacred Way from Elis (about which there are only assumptions), and architectural ones, such as the surroundings of the sacred site. There are also historical questions primarily concerning pre-history, as well as the between 1910 and 1912, but the major work was done in the 1920s which many consider the ‘golden age of the Institute’. Buschor was the director of the Institute from 1921 until 1929 when he went to the University of Munich, A dynamic teacher, he attracted non-archaeologists as well as professionals to his lectures. In 1925, he made the decision to resume the excavations on Samos although at that time most of the area had been uncovered. It proved to be a wise decision because important finds were made illuminating the early history of the sacred area. The Samos excavations were resumed in 1952, and remained under Buschor’s leadership until his death in 1961. They are now supervised by the present director of the Institute, Helmut Kyrieleis. One of the most important aspects of the Samos excavations, apart from the Temple of Hera, “has been the clearing of the Eupalineion, under the guidance of Ulf Jantzen, director of the Institute from 1967 until 1974. Mentioned by Herodotus, the aqueduct was built by the Megarian architect, Eupalinos for Polycrates, tyrant of Samos, in the late sixth century B.C. and is considered a major engineering feat of the time. Digging is only a small part of the work at all the sites. A glance into the storage shed at the Kerameikos reveals shelf after shelf of neatly arranged wooden boxes. Each box contains shards or other antiquities, each of which has been meticulously numbered. Each site employs a full-time restorer and often a photographer. Some of the archaeologists associated with a project restrict themselves to research on a specific subject.

Although even the great figures were at times guilty of errors in judgement or of pursuing false leads, the ‘forefathers’ of today’s generation of archaeologists are generally spoken of with reverence. A lifetime can be devoted to discovering the answer to a single query and much patience is required in an area where speed is no solution. Archaeology demands total commitment and the openings in the field are scarce—there are only a few hundred positions in Germany. One member of the Institute, who came to Greece for the first time as a junior member of Buschor’s excavation team in the fifties, said: ‘Once I decided on archaeology, I never wished for anything else but to work in Greece.’