Much has been written about the Southern European guest workers who migrated during the economic boom of the 1960s and early 1970s to the industrialized north of Europe. Many of these workers settled in the Federal Republic of Germany. Responding to the need for a larger labour force, they arrived from Spain, Southern Italy, Yugoslavia, Turkey. One of the largest groups came from Greece. An organized recruitment began in the early sixties when representatives from Northern European countries set up offices in Greece and other Mediterranean countries to contract workers. Before that, some companies had begun hiring on a more informal basis, among them Firm a Otto, a textile manufacturing company in Reichenbach, whose management, since 1960, has developed a somewhat paternalistic arrangement with its employees, all of whom are hired from an area near Alexandroupolis. Entire families have worked for the firm in Germany and since the establishment of a textile factory in Alexandroupolis in Northern Greece, many of Otto’s workers return to find a guaranteed job at home with the same company.

‘It was a smart idea, at least from the point of view of working climate,’ remarked one now-independent businessman formerly associated with Otto. ‘They avoided a lot of trouble, because one family watched over the other as in a large village. Theirs is a modernized feudal relationship,’ he concluded rather sardonically.

As the first signs of an economic recession became apparent in the early seventies, the recruitment of foreign workers slowly began to slacken and by 1973 it was officially stopped, a policy widely and often bitterly criticized by the workers.

Roughly ten percent of all foreign workers in Germany at the end of 1974 were Greeks, some 235,000 out of a total of over two million workers from abroad. This figure, compiled after the recession had set in, reflects a much larger share of returnees among the Greeks. Since then, the percentage has dropped further. At the end of 1976 only 169,300 Greeks remained in Germany out of a total of over one million foreigners. An explanation for this decline was offered by an official of the Baden-Wuerttembcrg Department of Labour: ‘The political changes in Greece in 1974 and the generally favourable development of the country’s economic situation was enough enticement for them to return/ ‘Nonsense,’ said a Greek who has been a long-time resident of Germany, is now a German citizen and is not planning to return to Greece. ‘The political situation has very little to do with their return. They have gathered enough money. They have built their houses back in the village or an apartment in the nearest town. Now they want to go back and enjoy life.’ The official provided some other interesting figures: Among the immigrant workers, Greeks have the highest number of family units. The percentage of Greek working-women is particularly high, approaching that of German women: 42.5% of the Greek workers in Germany are women (with 44.6% among the Germans). Among Yugoslavs 37% of the women work, among the Spanish 33%, among the Italians 28% and among the Turks a mere 24%. That the Greeks work hard and make good money is rarely disputed. They are thrifty and often provide for family members left behind, a phenomenon not unique to the Greeks in Germany. One can observe the same thing among Greek-Americans and Greek-Australians as well as among the Greek seamen working in various parts of the world.

It is difficult to ascertain if Germany has become a permanent home for most of these workers or if their intention is simply to earn money and return to Greece. The housing situation reflects one aspect of this complex issue. The Greeks have been especially efficient in finding accommodations; generally strong family bonds and traditions have made them the most welcome tenants in a rather closed small-town society. In addition, considerable effort has been made by employers to help workers secure inexpensive housing and assist them to set up their households. Other positive attractions are the overall favourable social legislation in EEC countries which benefits the guest workers and the local workers alike. These include generous vacations and employee and welfare benefits, as well as free medical insurance. Two charitable institutions, Caritas, associated with the Catholic Church, and the Diakonis-sen-Verein, associated with the Lutheran Church (the two largest religious denominations in Germany), have been especially active not only in providing substantial financial assistance to the needy but in helping guest workers adjust to their new community.

The workers have also been encouraged to participate in local affairs. A case in point is the Town Council of Esslingen, a medium-sized town with considerable industry and, therefore, many guest workers. The Town Council is an elected assembly representing a cross-section of the population. In 1971 it was decided that guest workers should be represented. Thus, ethnic groups with more than five hundred members now elect two representatives to the Town Council. Miltiades Kyrkopoulos and Panayotis Aslamides, who is also the leader of the local Greek Boy Scout Troop, sit on the council with Herr Pfleiderer and Herr Bechtle to decide on the town affairs. Nevertheless, there are those who question the success of such well-intentioned efforts to integrate guest workers into the local society. A spokesman of the Social Services Division of the city administration confessed that there were moments when he wondered if these efforts were welcomed. ‘Participation, for instance, in school affairs on the side of the Greek parents is very spotty and often disappointing/ he said. Wolfgang Haeckler, an Otto employee, observed: ‘Of course, they invite us to their weddings and baptisms, but basically there is only a superficial level at which they mix with the local population.’ He adds, however, emphatically, ‘This is not the fault of the Greeks. Our own people are so stern and so firm in what is right and what is wrong. We could learn a great deal from the Greeks.’

Guest workers are, of course, not the only Greeks who have settled in Germany. Greek professionals, intellectuals and businessmen, although few in number, have not only taken an active part but have made a considerable contribution to German society. Among the more renowned is Professor John H. Argyris, the Director of the Institute for Statics and Dynamics at the University of Stuttgart and an internationally-known scientist in the league of the late Wernher von Braun. Another is Professor Takis Zonos, the well-known neurosurgeon at Stuttgart’s Katharinen Hospital.

Many who came to Germany to study have remained because of the more favourable educational and research facilities. Stylianos Flamourakis is president of a school of economics in Stuttgart which has four hundred students and a forty-eight member faculty. His wife, Lena Flamourakis-Blatsoura, a sculptor and painter of considerable repute, has found a most unusual niche in Stuttgart life. Many of the city’s historic buildings, which date back to the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries when Stuttgart was the residence of the Kings of Wiirttemberg, were severely damaged during the war and in need of extensive restoration. Mrs. Flamourakis has for several years been working on the restoration of the sculptures crowning the facade of the New Castle and repainting the Moorish Rotunda at the Wilhelma, another royal palace. Now, gradually, the work load is lessening, and she finds more time for her own work. She recently sold a bronze sculpture and is preparing for a large one-woman show in early 1979. Her studio is located in an incongruous factory neighbourhood in Fellbach, at one time a vineyard area and now a suburb of Stuttgart. Their home is a tastefully furnished modern flat. Do they feel at home here? Very much so. Most of their friends today are Germans, or Greeks married to Germans.

There is also a substantial number of successful small businessmen, many of whom came originally as workers but eventually set themselves up in their own business. While shopping one morning, I came upon a package of oregano with the. label, ‘Panayotis Kristallidis, Importer of Foreign Specialties’. When I called his office I was told by Mrs. Kristallidis, who spoke a perfect Swabian dialect, that her husband was far too busy to see me and at the moment was away on a business trip calling on his customers in the region.

Looking for a place to eat in Esslingen recently, I headed for the Rathskeller, a restaurant I have known since childhood. It was closed, and a sign in the window announced: Open from 5 p.m. to 2 a.m.’ —rather unusual hours for a German restaurant! The menu posted outside listed, in addition to the traditional Swabian specialties, a variety of Greek dishes including fasolada, dolmades, and vlahiko (‘a Greek peasant feast’). The current owners of the Rathskeller are now M. and P. Carpatis.

In Reichenbach, I visited twenty-eight-year-old Paschalis Futsitzis, the proprietor of the only open-air fruit-stand in town, located across from the ultra-modern city hall. His prices were high, I was told, but his fruit is the best in town. Speaking in a charming but heavily-accented Swabian-German, the animated young Greek introduced me to his pretty wife, Gisela Futsitzi-Schneider, whom he had met while attending high school in Reichenbach. He has lived in Germany since the age of fifteen when his father came to Germany to work for a textile company. He spoke of his early years in Greece, in a village near Alexandroupolis. As a child he had accompanied his family to the local market where they sold produce grown on their land. Therefore, he explained tome, he knew ‘everything about fruits and vegetables’. Today, he combines good-natured complaints about his long working days (he gets up at four in the morning to drive to the wholesale market in Stuttgart) with unabashed pride in his success. With hard work and ‘ein bissle Diplomatie’ —a bit of diplomacy— he managed to secure the present location for his little enterprise and to put up the stand on the sidewalk (against local ordinances, but in full view of city hall). He is now preoccupied with the construction of his first apartment house. He has no plans to return to Greece.

The Linden-Apothcke, a beautiful, old-fashioned shop located in Gablenberg, one of the oldest parts of Stuttgart, is owned by Aristotelis Hadjielef-teriadis. The decor brings to mind the alchemists of past ages. The Greek proprietor proudly shows me the computerized storage and filing systems he has installed.

Hadjieleftheriadis assures me he feels as much at home here as in his village in Greece. His neighbours, mostly poor and generally reserved, brought flowers to the pharmacy when they learned of the birth of his second son, he tells me. His wife, Hildegard, a tall, blonde German woman, is also a pharmacist. Sitting in his office, he speaks of his humble beginnings, his studies at the University of Athens and his dream of an academic career which he was forced to abandon. One of his professors had bluntly told him, Ί became a professor because Τ married the daughter of my professor. Sorry, young man, my daughter is already married. I advise you to go abroad.’ He followed that advice and is proud of his success. He has built his ‘retirement home’ in Greece, however, in Eretria, on the island of Evia, where it is locally referred to as ‘the villa of the German’.

Altbach is a small village on the Neckar River, with a population of a few thousand. Once a small cluster of farmhouses, it has now been swallowed up by urban expansion. I make an appointment with Dr. Nikolaos Grammenos who tells me, with Germanic precision, that I may see him on Saturday morning at nine. He has breakfast with his family at eight, he explains, and begins his house calls at ten. On the Saturday we chat in his modern, elegantly furnished new office which is colour-coordinated right down to the wash basin. Trained in Berlin, Dr. Grammenos describes the intensity with which he and his fellow students in Germany had studied. In many ways our chat summed up the previous discussions. He had intended to return to Greece after completing his training and had even hoped to build a clinic on some property he owned in Katerini in Northern Greece. A short period of volunteer work in the local hospital erased some of his illusions. He spoke of the pressure to come to his decision, his awareness of a ‘different mentality’ prevalent here. ‘How much time we had to spend just to renew our passports!’ he observed. The deciding factor came in 1965, when he returned to serve in the army. ‘We were in a camp in Korintlios. Despite the fact that we were all expected to check in at the camp, there were no uniforms, nothing was pre-pared. They had to fly in tents after we had spent the first few nights sleeping on the ground.’ He found it all too disorganized. At the conclusion of his military service he decided to return to Germany. He met his wife, a German nurse, at the hospital where he served his internship. Asked whether his two small children speak any Greek, he smiles, ‘No, only the Swabian dialect.’

Does he think of going back to Greece? ‘For vacations, yes. We did not go for many years because of the Junta. This year we could not afford to leave because of the new house and the building. But perhaps we will go in the coming years. The children may even learn to speak Greek. But to work there? No. There is now too much investment right here.’ Js he happy? Yes, successful, too. And, what counts heavily with him, he is doing what he always wanted to do. Yet, there is a touch of sadness in it, a desire to reaffirm to himself how well off he is, that he made the right decision.

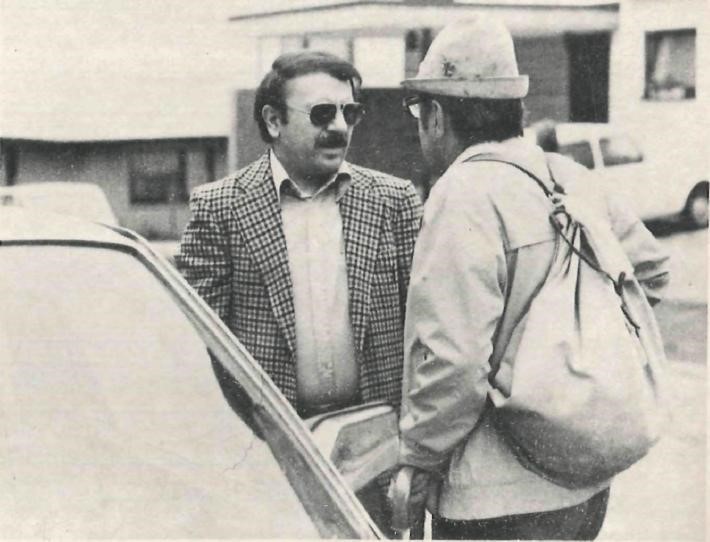

On the street he meets one of his patients. They exchange greetings, the impeccably dressed Dr. Grammenos about to drive off in his Mercedes, and the patient with a rucksack on his back. Dr. Grammenos does not really look like one of them. But his children will.