Photographs by Margot Granitsas

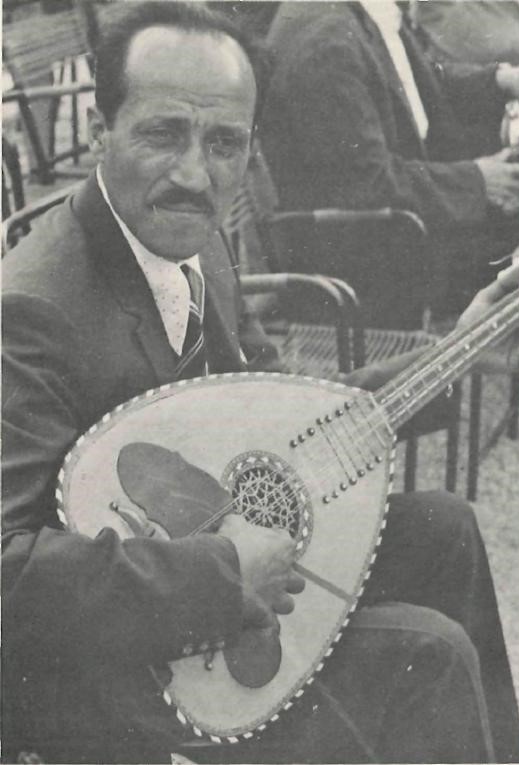

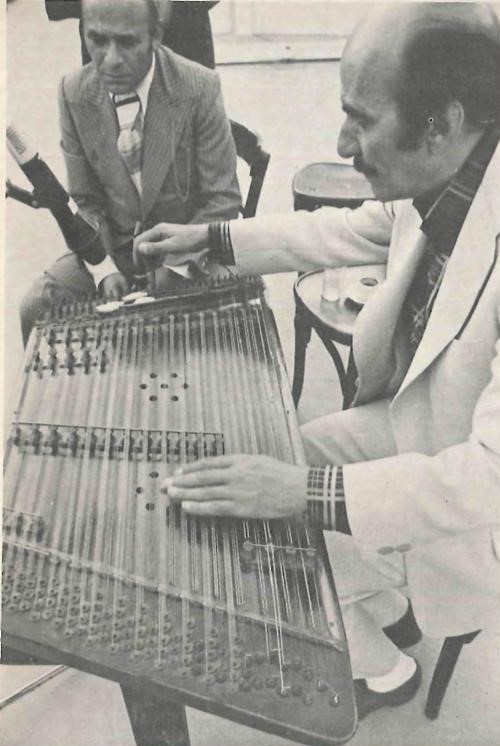

There is no manual on how to build the instrument he plays, but the kanonakiis not markedly different from the zither like psaltery or dulcimer. Trapezoid in shape, its back is made of linden wood, its top of plane wood over which are drawn the nylon cords which now replace the original catgut. Nikos Stefanidis, a retired watchmaker in Nea Ionia, plucks the strings with metal plectra attached to his index fingers with chiseled silver bands as he explains that the use of the kanonaki can be traced to the Old Testament and Byzantium. It was later adopted by the Turks and Arabs.

Stefanidis began playing as a child in Constantinople where his father owned a hotel. Many of their guests were from Smyrna which was noted for its Greek folk music traditions In 1923, after the Asia Minor Disaster, his family left Turkey, he explains fingering his old, richly-decorated instrument which was brought from Constantinople. The only kanonaki maker in Greece today is very old now, and produces a single instrument a year.

Nikos Stefanides was one of a small group of musicians who performed, sang and improvised on June 27 at a concert of old Greek musical instruments organized at the Aliki Theatre in Pedion Areos by the Association of Greek University Women. Up until recent times, these instruments were played wherever Greeks gathered: in coffee shops, at weddings, baptisms and festivals. On this occasion the musicians performed on a stage against a wrought-iron backdrop that combined elements of New Orleans and Louis XIV with fin-de-siecle candelabra and white, plastic clematis climbing up an imitation brick wall. The setting had precious little in common with a coffee shop in Kozani or Alexandroupolis.

‘It is our first venture into the musical field,’ comments Lady Amalia Fleming who has been president of the twenty-six-hundred-member organization since 1975. ‘The previous committee used to organize teas. We prefer to do something like this. Besides, we had no money left, so we thought we must raise some money for our activities.’ Winking in the direction of a man who had just gone over some details concerning the receipts from the tickets, she adds, ‘As you see, the tax man is already here.’

The crew from the two television stations is busy setting up lights. They look like any television crew anywhere in the world. They are young, in blue jeans, and fortify themselves with the occasional whiskaki. Their methods are not quite as elaborate as a major American network crew preparing for a convention coverage. Their approach is rather casual, if not primitive. Yet it is a valid effort that will transmit the music to a wide audience that may not have access to the University Women’s Association.

‘Work is much better now in Greece,’ says the widely-travelled Petros Kalivas who has resettled in Greece. He plays many instruments, the lagouto, a long-necked lute, the gitara, a guitar, the floyera, a woodwind instrument similar in tone to a recorder, and the outi, a short-necked member of the lute family. Originally from Mesolongi, he kept company with other Greeks during his many years abroad. He lived for some time in Boston and in New York, where he played at the Britannia Club, one of the now-popular night clubs around Eighth Avenue where Americans have come to believe that belly-dancing is a Greek pastime.

As the preparations for the concert proceed, a predominantly young crowd streams into the theatre, quite punctually and, as it turns out, more or less by mistake. (Lady Fleming later apologizes for an error in the announcement which gave nine o’ clock as the hour of the performance. This satisfies my curiosity and explains why everybody seems to be in his seat by ten p.m.) Among the spectators, there are many beards, blue jeans, long peasant skirts, and young children in the arms of their parents or seated in strollers.

The first four musicians who take their seats on stage look like an odd lot. Alekos Moschos, a grey-haired Roumeliotis with a finely-featured face, wears a rumpled grey suit but no tie. He plays the laiko violi and his improvisations are catching. In appearance the instrument is not very different from a contemporary violin, but it has a distinct tone. Not exactly a Menuhin, Alekos Moschos evokes a combination of totally personal music in which one can hear whatever one likes, from Puszta melodies, to bird songs, to funeral dirges. One wonders if he ever plays the same tune twice. After a while he begins to sing. His voice is strong and youthful, belying his grey hair. He delivers his songs without affectation, standing straight as a rod before the microphone. He is thoroughly disarming.

With him plays another Roumeliotis and a namesake, Aristidis Moschos, holding a sandoun in his lap, a smaller zither-like instrument with strings in threes and fours drawn across its width. Its range covers three or four octaves. A metallic sound results when the strings are vibrated with the hammers — two thin batons with cotton pads affixed to the end. The harpsichord (a much larger instrument) is a direct descendant of the sandoun and produces surprisingly similar sounds.

Aristidis Moschos looks more like the prototype of a nightclub performer. He has a carefully groomed moustache, and is wearing a flamboyant lemon-yellow shirt. He has just sent the mikro, the message boy, to fetch his green tie. ‘Kai mia lemonada,’ he told him, pulling out a rather fat bundle of green bills. The listeners are clapping their hands in rhythm, as Nikos Papavranidis plays on the Pontian lyra. He sings in a hoarse voice about marriage. It sounds more like a dirge than a merry wedding song. Not always following the lyrics, I assume that it must be about heartbreak. His delivery is totally unassuming as he sits on the stage in a short-sleeved white shirt, playing his crude little wooden instrument all by himself and seemingly for himself. His fingers touch two strings simultaneously so that a counterpoint effect is produced, with a second melody accompanying the first. The Pontian lyra, also called a kementzes, is held on the knee and played with a horse-hair bow. In 1923, Papavranidis came to Greece with his family from Pontos, on the Black Sea coast of Turkey. He proudly shows me receipts from his performances on radio, and tells me that he has been a member of the radio orchestra for thirty-five years.

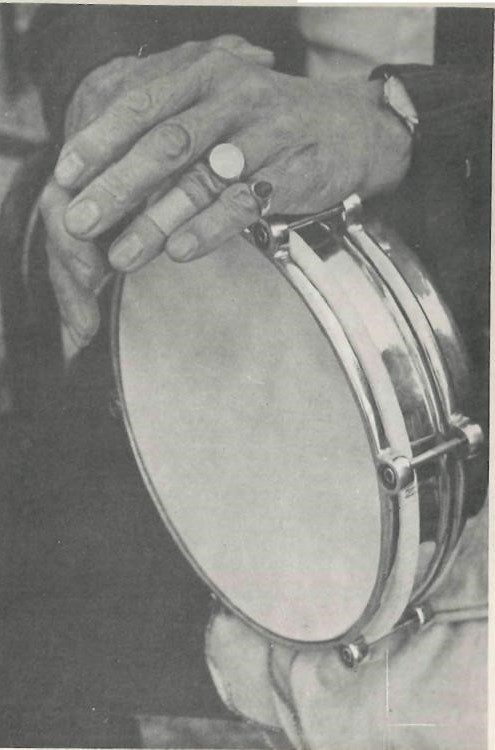

People are coming and going in the theatre. One feels that they are participating. They listen, they clap their hands, they stomp their feet in rhythm with the music. They laugh when the lyrics are funny and folksy, or when Matheos Balabanis from Constantinople plays the toumbeleki, a skin-covered small drum perched on his left knee. With a smiling, puckish face he drums a monotonous but varied rhythm. He drums and drums and drums ad infinitum.

Tassos Anastasiou is thirteen years old and came here from Cyprus. He is in the second grade of the gymnasium. He lingers among the musicians. Not knowing who he is, I ask if he plays any instruments. Oh yes, he informs me, and enumerates a long list. A little genius, I assume. He likes to make music, he says, and plays all day long. He learned to play all the instruments by himself, and wants to become a musician when he grows up, he continues — until his father who runs the snack bar calls to him. At that point Young Tassos dons a white apron and begins assembling a tray of lemonades and snacks to be served later to the concert-goers.

One of the most unusual and fascinating instruments, still found in rural Greece, is a bagpipe-like instrument, the gaida, its large bag made from goat skin. The musician holds this in his arms like a small child, while his fingers play on a short, perforated wooden tube protruding from the sac. The air is blown into the bag through a second tube which has a mouthpiece. This tube is pieced together from several segments, the length of the tube controlling the pitch. A third short tube with a lid acts as a valve to prevent the air from escaping from the sac when the player takes a breath.

Theodores Keres plays the gaida and the kavala, the latter a very-long, wooden flute whose segments are joined together with beautifully-etched brass rings. Glass pearls decorate his gaida like the feathers of a rooster’s tail, and he fingers these while describing his efforts to make a carrying bag for his gaida. One like those they used to have,’ he explains. They could be attached to the belt when the instrument was not in use. He now makes his living as a concierge in Kolonaki. After seeing him pull out his beautiful old instrument from a plastic shopping bag kept inside a plastic tote bag, I encourage him to continue his efforts and do not disguise my feeling that he should improve on the style of his instrument’s carrying case.

Eleni Karaindrou, a composer and musicologist who organized the program, introduces the players. A willowy young woman in jeans and a white peasant blouse, she is largely responsible for this and similar concerts. We talked about the kind of music and musicians presented that evening. ‘These are extraordinary musicians,’ she says, recounting how she found them gathered in an Omonia Square coffeehouse playing in their leisure time. ‘It is hard today for these musicians to express themselves as they used to. We are conditioned by the music heard on the radio, on records, in movies. There is no written music for these old instruments. The melodies are transmitted by ear in the villages. ‘There are few who continue the craft of the old instrument-makers and many instruments are home-made.’

Karaindrou became interested in the folk aspect of Greek music while studying in Paris. She made contact with Greeks living in France who still played the old instruments. A composer in her own right, her songs have been recorded by Maria Farandouri, and she has written the scores for two films, Takis Kanelopoulos’s La chronique d’un Dimanche and Dimitris Mavrikos’s Polemonta, a feature-length documentary on the Greek-speaking settlements in Southern Italy which date from classical times. Her own music has been influenced by Greek folk-song music, says Karaindrou who was born in Roumeli, ‘But not because of my research into the subject, rather because I was born and brought up in a Greek village ‘.

The interest in that oral tradition is on the increase, however, among younger people, she feels. In 1976 the ORA cultural centre organized a series of lectures and, subsequently, informal, instruction on these ‘endangered’ instruments. Listening to Miss Karaindrou, one senses the urgent need to preserve those traditions now succumbing to modern-day life as more and more of rural Greece streams into the cities, where weddings are celebrated in a different fashion, and feast days are occasions to go to the beach rather than to assemble in village squares or in the fields to eat and drink and dance and make music together.

The evening is warm and pleasant, the music is catching. One forgets the plastic clematis and the theatrical, wrought-iron grill behind the musicians. The television lights blow a fuse and the sounds are momentarily dulled, but everyone starts to hum, to clap, to listen to the hoarse voices, the monophonic music. The village atmosphere prevails until one hears, loud and clear, the voice of the little boy, Tassos, the one who plays ‘all those instruments all day long’ and wants to become a musician when he grows up. In his white apron, he approaches, bellowing in pure, unaccented Greek-English: ‘Shees Sandiches, shees sandiches.’