In my wife’s village where we live, the country folks’ hospitable instincts have risen to the fore to provide visitors with the local colour they seek, and thus, to send them home with memories that reinforce their wildest fantasies of Greek village life: a blend of unsullied primitivism and ancient pagan rite. Formerly known as Kookoomelata, which is untranslatable, the village has been renamed Chrisipigi — which means Golden Spring. (Natives, of course, continue to use the old name.)

It all began ten years ago when one of our native sons Dimitris (Tzimi) returned home after being deported from America (for reasons unknown) and decided that the skills he had acquired abroad should be put to good use to improve the welfare of the entire village. He called a meeting in the central square at midday. Since most of the town’s male citizens had already been gathered there from early morning, he immediately had a quorum. After a morning of hot sun and ouzo, there were no protests among the assembled townspeople when he announced that we were going into the tourist business and going to make money. He appointed himself Mayor and Tourist Development Officer. Before we knew it, he had put us all to work and made us rich. Today every family in our new village of Kookoomelata has a car and money in the bank, every house a television, luxurious furnishings and imported delicacies in the refrigerator. Within another five years all the houses will have full air conditioning.

When I say ‘new village’ I mean the one in which we actually live, the one that the tourists do not see, which lies concealed and unsuspected behind a hill. The old village is now only our place of work. During The Season, which lasts for only a few months, buses shuttle us back and forth between our homes and business where we can be seen by tourists wandering through the shambles of the old village wildly contented with our seemingly total deprivation — in a ‘primitive euphoria’ as the guide describes it. The rest of the year the old village is unoccupied and neglected so that it becomes more authentic by the year. Semi-wild goats leap from one sagging rooftop to the next, hens and turkeys roost in the rafters, and sheep meander in and out of the houses through holes in the walls.

‘How is it’, the tourists ask plaintively, ‘that they have nothing and yet they are crazy with contentment, and we have everything but can’t find peace of mind? What has gone wrong with our civilization?’ The standard answer (interpreted by the guide) is: ‘We follow the ways of our fathers and grandfathers and great grandfathers. We want little, we ask for little, we receive little. But we love much. True wisdom lies in the soil and toil. Vouno, the God of the Mountain, has taught us this.’

The success of ‘Project Chrisipigi’, as Dimitri dubbed it in the early years, has been the result of the most meticulous planning. Although the tourists who arrive by the busload are invited to go anywhere they please, in reality the groups are shepherded from place to place and from one ‘spontaneous incident’ to another, according to a carefully worked out strategy. We stage at least seven incidents — ‘human, everyday facets of normal village life.’ These are spaced out along the route and are but a prelude to the main attraction: a visit to the Original Cave of Pan. If I must say so myself, they are all Oscar performances.

Such organization would not be possible without the central control room which is located in the old watch tower overlooking the village. Short wave transmission and tiny receivers guarantee a smooth operation. (‘Group A is now approaching Sector 6. Group Β has thirty seconds left of Incident No. 1. Flower girls, stand by to walk down the lane now and so on.)

Tourists are received at the east end of the village and depart from the west end. Upon arrival, they are greeted by the Mayor who announces: ‘Go where you choose, you will be welcomed with a smile. We open our hearts to receive you. Henceforth you are not strangers, but friends!’ Every tourist gets a personal handshake. Women in local costume strew sweet-smelling herbs (‘a traditional expression of welcome probably introduced by the Romans’) and distribute glasses of powerful cognac which take effect immediately. To conclude the ceremony, the village band erupts into a wildly joyful and uninhibited rendition of ‘Never on Sunday’.

The first stop, at the House of Spiro, allows the tourist to sample a ‘typical day in the authentic life of a typical peasant’. Spiro emerges on cue from his place of concealment with his donkeys, trudges wearily down the narrow lane which leads to his house (‘returning from a day’s toil which began at sunrise when he set out to walk the one hour’s distance to his vineyards’). Both of his donkeys are heavily laden; Spiro carries on his shoulder a spade and billhook. He enters his house, a rude abode whose windows, although faithful to the local architecture, have been so constructed that up to one hundred tourists at a time can get an unimpeded view of the interior.

The tourists are understandably reluctant to take up viewing positions, but the guide assures them that this is not considered a breach of etiquette since all villagers lead completely open lives with no secrets to conceal: any villager may walk into a neighbour’s house at any time of the day or night. Their reluctance overcome, the tourists are soon engrossed.

‘Spiro’s wife, Aliki,’ says the guide, ‘is bringing him a platter of bean soup and two loaves of home-baked bread. See with what avidity and delight he consumes it! Hard, honest toil in the fresh air needs no sauce. Now he is replete and, throwing himself on the wolf rug before the fire, divests himself of all his clothing whilst his wife strums the old lyre. See, he now takes the Love Water of Aphrodite’.

‘Does he do that every afternoon?’ ask the tourists in awe.

‘Every afternoon and all night,’ says the guide, ‘and continually at the weekend.’

‘It is only possible,’ she adds, ‘on a diet of bean soup and the Water of Aphrodite.’ Tourists come away from Spiro’s house shaken, the men silent and thoughtful, the women flushed.

‘Fantastic, just fantastic!’ they whisper, ‘But, of course, he must be exceptional…’

‘Not at all.’ replies the guide. ‘He is quite average. That’s just the way life is here. Unsophisticated, straightforward, urgent — an innocent fecundity.’ (I sent a memo to the Mayor suggesting that a guide who can come up with expressions like ‘innocent fecundity’ ought to be given a bonus and how about putting it into the official commentary. He has okayed this.)

Around the corner they come upon The Old Man Whose Time Has Come To Die. He is seen being escorted by his howling relatives to the family ‘dying place’ on the mountain. Although I have seen him depart thousands of times, the performance still brings tears to my eyes. The relations make all the noise, while the old man is serene and lit up with mystical exaltation ‘as befits one who has lived a rich, rewarding life’.

For purposes of contrast, this is followed immediately by The Youngest Son’s Departure for the Big City. This includes a tugging match between mother and son. Inevitably she submits to the inevitable. There are the traditional last gifts of hard cheese, bread and olives wrapped in the traditional red cloth. The Young Girl (his promised bride) is expected by custom to try to prevent his departure by clutching him like an octopus around the ankles. The further she permits herself to be dragged, the more honour accrues to her. The tourists are not permitted any expression of sympathy. The guide informs them that it would be considered a discourteous intrusion and quickly leads them to The Newly Married Couple.

This is designed to lift the tourists’ spirits after the emotional mauling they have had with the first two. The couple is leaving the village to spend the traditional twenty days alone on the mountain. A six-piece band and a mob of exuberant villagers hurling rice, sheep pellets and good-natured obscenities appropriate to the occasion send them on their happy way. The bride carries a horseshoe of solid silver with which she playfully strikes her husband on the head. According to the guide, this custom goes back at least three thousand years and, although once practiced throughout the country, is now exclusive to this village.

The celebration of Olive Tree Day comes next. The tourists are told by the guide that by the most fortuitous coincidence they have come on the day which marks the observance of this most ancient rite which is at least ten thousand years old. Peasants, with cymbals attached to the inside of their trousers at the knees, dance a sirtaki around the oldest olive tree, exhorting it in a four-note song to go on producing olives. The tourists are invited to join in. Wine, cheese and garlands of olive leaves are offered to them.

This interlude is followed by The Manhood Initiation Ceremony. By another amazing coincidence the tourists happen to have come on the only day of the year when this supremely important event takes place. Unfortunately, the guide tells them, the ceremony is secret and cannot — on pain of death — be seen by an outsider. The Sacred Enclosure may, however, be approached to within a distance of one hundred feet, marked by a low wall of ancient marble on which are displayed the skulls of unauthorized persons who tried but failed to beat the taboo. Meanwhile, if the noise comingfrom the Sacred Enclosure is any indication, something horrendous is going on within. Against a background of beating drums and barbaric chants, bloodcurdling screams (animal and human), cries of despair and appalling groans emanate from within the Sacred Enclosure. This is all done by tapes and amplifiers.

The tourists, speechless with excitation, move silently and thoughtfully on to The Oldest Villager. This is a charming cameo performance. In the distance a group of little girls can be seen approaching with bunches of flowers. They are on their way to pay the daily floral tribute to their great-great-great-great grandmother who is 157-years old. The tourists are invited to follow the children into the garden where the Oldest Villager sits dozing in the sunshine.

Maria really looks 157. My wife who was her classmate in grammar school assures me she always has. As the girls begin to perform the ritual dance, Meres Polles (Many Days), Maria wakes up to reply to the inevitable questions about the secret to her longevity. Her only secret, she explains, is a sparse diet of water, yogurt, and garlic. Many tourists feel impelled to slip a banknote into her unsuspecting old hand. (When full, the hand disappears swiftly into her dress and reappears just as swiftly, again empty and unsuspecting.)

The Genuine and Original Spring of Aphrodite is the Mayor’s greatest brainchild and our biggest money-spinner: the sale of bottled Love Water from the Golden Spring (‘from which the village takes its name’) and the booklet ‘Secrets of the Sex Goddess’ bring in twenty thousand drachmas a day. The setting is so authentic that if Aphrodite were to return she would have no difficulty in finding her way around. It is as it was ‘when the world was young and inhabited only by gods.’

‘Upon all the gods Aphrodite bestowed her favours liberally and indefatigably,’ the guide begins. After a lengthy dissertation on Aphrodite’s activities, the groups are led to the kiosks where the Love Water and the Booklet are sold. The turnover is gratifying.

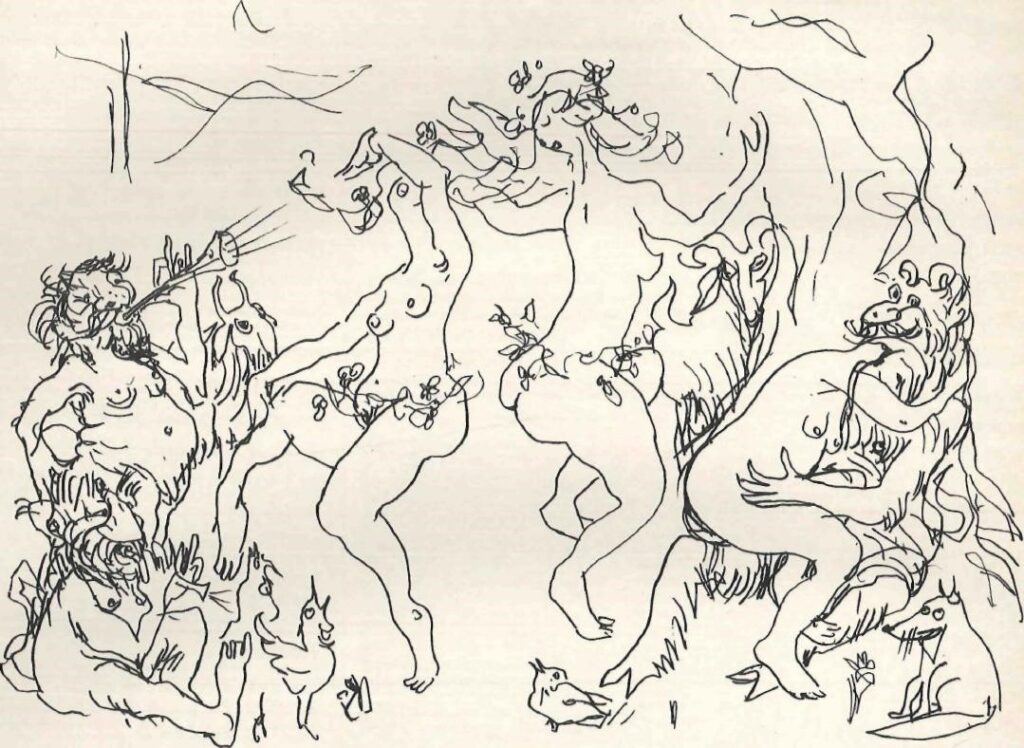

Finally they arrive at the Original Cave of Pan. Our Pan (‘untiring in his lewdness and lasciviousness’) is not some old half-goat, half-man who lived and died thousands of years ago, but alive and gruesomely realistic. If 1 didn’t know his true identity, I would find him irresistible if I were a woman.

We present some scenes from his early life in Arcadia, vividly illustrating the sort of things he got up to and just how he earned his kinky reputation. If this were a film, we would never get away with it, but offered as Historical Mythology it has been applauded by several ministers from whom we have received flattering letters. (Our village priest, while murmuring disapproval, has been forced to acquiesce.) The performance climaxes when the Cave is plunged into complete darkness. The inference is that Pan takes full and frenzied advantage of this opportunity. At any rate, the lady tourists emerge from the Cave bright-eyed, and agree-ably and deeply impressed by the curiously shocking ‘touch of authenticity’ administered by a feather duster attached to a long handle.

The Departure Point has the usual Arts and Crafts Shop and a Pavilion in which coffee, cokes and cakes are sold. It is surprising how grateful people (who have perhaps spent a thousand drachmas and more on our products and thought little of it) are to be charged a few drachmas for a coffee which they are well aware would cost them much more in the city. We know by simply looking at their faces that they have had a memorable trip. It is the laudable aim of our enterprise to provide the stuff of which indelible holiday reminiscences are made.

As they board their buses, our wandering bouzouki troubadour sings that very old and sentimental song ‘No, No, Stay Yet a Little While Sweet Yanni Mou’. All along the way to the boundaries peasants ‘working’ in the fields will pause to wave a friendly salutation. We are planting well the corn’ for tomorrow’s crop.