It is the day before Good Friday. Already people are letting off fireworks from time to time, day and night, all over Athens; they will rise to a crescendo in a couple of days time, at midnight on Saturday. Meanwhile, these chickens are Easter gifts for your lady friend. As we struggle through the noise and the car fumes of the streets below the Acropolis, we hear even above the noise of traffic the desperate, though feeble, cheeping of live chickens. One or two days old, they are huddled in shallow cardboard boxes on handcarts at the roadside, and are sold to passersby. There are thousands of these chickens and dozens, if not hundreds, of handcarts loaded with them.

Is this a modern version, innocent of blood, of the pagan sacrifice when blood of chickens was fed to the roots of growing corn? What are flat-dwelling Athenians to do with these chickens? Are the flats to be infested with poultry? No: these chickens are to be sacrifices, also. They will not be killed at the height of a religious ceremony; they will die as toys in the possession of ladies and children.

The chickens are handed to you in a cage, the shape and size of an Easter egg. Some are even sold inside an egg-shaped, plastic bubble; tiny flecks of birds, limp within their steaming prisons. One flashes an eye, one stretches a feeble wing — they are alive! If they reach home alive, the chickens might just survive through the Easter holiday week, before they arc mauled or starved or, perhaps, trodden to death.

Well, the English kill and eat millions of turkeys, geese and hens to celebrate the birth of Christ. But perhaps to be quickly killed and eaten is merciful compared with the slow deaths of these specks of flesh, that are worn as decorations by ladies, added to gross displays of gold jewelry; or given to children to torment.

On Good Friday, I am told, it always rains, to mourn the death of Christ, but that the sun shines for His Resurrection. The rain prevents my wife’s father and mother, who are the most ardent of churchgoers, from attending church this Good Friday evening. Instead, they watch the service at the Cathedral on television. Each holding a prayer book and following the service carefully, line by line, and furious if they are interrupted, they sit together in bed and give the service the kind of attention that my father used to give to televised football matches.

At about half past eight, my wife and , I go out into the rain, and her mother crosses herself, to defend us from the consequences of our madness. The church, though, is full of people who have braved the rain. It is too full for us to be able to enter, so we buy our candles and stand with the crowd outside. Hundreds of candles flicker unsteadily in the rainy wind, in the uncanny quiet. There is only the hiss of the wet wind and the booming waves of the service to which the people listen intently, under the damp pine trees. For a very long time nothing seems to happen. We stand motionless, in almost total silence, reached now and then by what sounds like a distant mutter of the sea.

Then the great, grey bell slung from a pine branch begins to toll dismally. The church door is opened. There is a flood of yellow light. Little boys in silk gowns burst out, surrounding a man in a black suit who is carrying a crude black cross decorated with three burning candles — one on each arm, another at its peak. Behind him is the priest, in gold vestments, carrying a gold Bible; the focus of the gold light. Then come four men bearing the symbolic body of Christ: a black cloth scattered with flower petals. After them come four men with a fretwork ark. The bearer nearest to me is a beefy, embarrassed young man with a smooth face and cowed eyes. He wriggles, sweating, in his collar. He takes one hand from the ark to loosen his tie. His mother, a shriveled, proud little woman standing by — surely she is his mother, with all her blood but none of her fire gone into this son — hands him a handkerchief with which to mop his brow. Over the loudspeakers, a priest begs us to return for the service after the procession; he knows, alas, that the old people will go home to their television sets, and that the boys will pair off with the girls and slink away.

The ark is decorated with tiny red lights which sway into the darkness. The rest of us, bearing our candles, mass behind and form a procession through the streets.

We go to the front, in between the ark and the Cross, where about a dozen people lead the singing of a tune which has such pathos, it is hard not to cry. There is an old, assertive man who perhaps feels that, having done this every year for so many years, he is with this singing guarding his very life, his childhood, his immortality — and so triumphantly that it has yet again stopped the terrible Athens traffic. There is a tall, bovine girl in a sack dress, who trundles along like a buffalo, boldly singing and looking as though she feels that she is leading a revolution. There is another old man, his jacket collar raised, who holds his hat against his throat as he marches. He has a big grey moustache, and a weather-marked face, and is from Crete, perhaps; at any rate he is from the country or from an island. And perhaps he represents the peasant, accepting and even proud to stoop beneath church and state.

More people buy candles and join the procession as we move; so eventually there is a huge crowd. The residents of the flats light candles on their balconies as we approach — some only one candle, others half a dozen of them. The whole narrow street, with flats five stories high, is alight, and a seething mass of flames slides down the street; and the only sound to accompany it is our steady, mournful singing. Some people cross themselves as we approach. Some people dab at their eyes. It is very moving.

And very modest. No one is taking photographs or making tape recordings. But only a mile away, in Constitution Square, Christ is given a grand military funeral, with thousands watching and taking part and photographing it. The American tourists, and the residents of the Hotel Grande Bretagne, flit around with their cameras, and poke them between the lines of the policemen; and run across the street; and even poke their cameras over the peanut stalls. The tune that we sang so movingly and simply a few moments ago is here hammered out by a military brass band, at a pace marked by the heavy footsteps of soldiers and government ministers. They are guarded by lines of marines who carry their rifles pointing downwards. At the end of the procession comes a detachment of military police — tall men, as fit as tigers, with machetes and guns. And this, I will remind you, is a ‘funeral service1 for Christ.

But people are truly jubilant on the following day. An hour before midnight, we go to a huge concrete church on a hill. The church stands before a spacious square, crowded with people. Each holds a tall candle.

We buy our candles at the kiosk and join the crowd — again, we cannot get anywhere near the church. The priests, floodlit in a forest of standards, chant from a raised dais in the centre of the square. Their chanting is relayed through loudspeakers; nonetheless it is impossible to hear anything because of the noise of fireworks. They shoot off from all directions — from under our feet; from the tower of the church; from the balconies of flats — an indiscriminate firing that makes you wince.

And after we have kissed one another, and gone home for the traditional supper of mayeritsa — a thick soup of liver and vegetables — then comes the traditional cry of the city dweller.

‘Ah, but you should see this in the country!’ I am told.

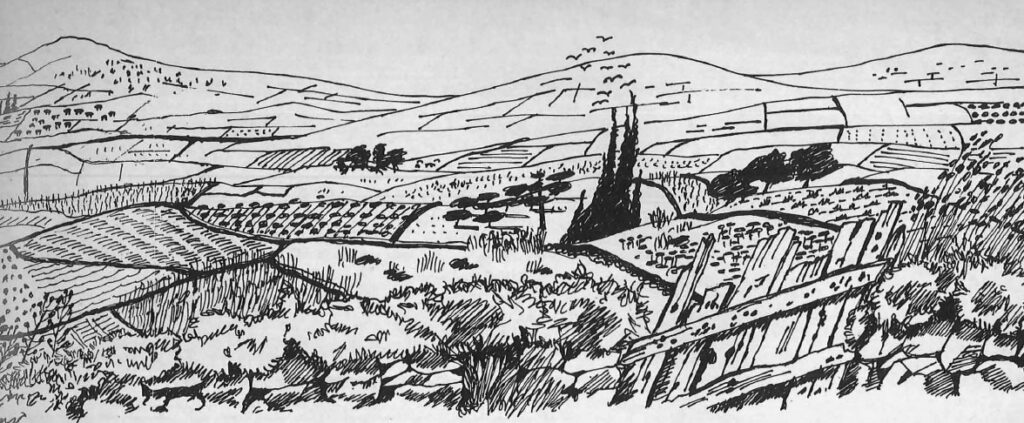

TWO hundred kilometres from Athens, the road to the town enters over the thorns of a fierce countryside. A wandering, beautiful. seemingly-meaningless line follows an old track made to link the huts of fishermen and shepherds. It plunges towards tiny bays by the sea and rises over weather-chewed boulders and dusty, brittle, unwelcoming herbage where the thistles flower in a powdery, insubstantial blue. The sky is more firm and more definitely blue; it is the thistle flowers that are mysterious and intangible, not the brass-hard, even sky. Occasionally a hawk dashes, loses impetus, sways and falls away; the sky is too hot, too hard, and too dry for any other bird. A peasant, shuttered in ragged and dusty clothes to keep out the sun, stares balefully at the bus, which sounds its klaxon at every hut. The peasant expresses nothing other than what a stare automatically expresses; his stare is private; it is as if he is looking after a vanishing wish of his. He is as enduring as the cicadas under the sun — which also seem to be without flesh.

Then come olive trees. There are unfenced strips of wheat; and gardens green with sweet-corn and beans; and flocks of goldfinches fussing over them.

The peasants invest their savings in holiday villas that are built in stages — a little bit more every two or three years as their savings collect. So the town is ringed by optimistic foundations, surrounded by prison-camp wire. In two years time, if the olive crop has been good, the walls and doors will be finished. The ground floors are completed with hairy strands of iron sticking from the roofs to support the concrete pillars of the next floor, which might be built five years later. Meanwhile, goats are penned in the villas.

The town itself seems to be all chairs — little iron ones, laced with party-coloured plastic strips; or old-fashioned wooden ones, like the ones that Van Gogh painted. But of course the chairs have tables, and blue, enamel-surfaced sea to accompany them. Behind them, where you are not quite invited to go, a solid glare of concrete faces the unsewcred alleyways of the ‘real’ town — the goats and mules and hens and people; the high, blue-domed main church in its square of dust where the priest parks his canvas-topped van; the low houses with red-tiled roofs, their eaves decorated with rows of dull-red, ceramic acanthus flowers, their gardens dense with orange and lemon trees; and the dusty places where the children play with all kinds of young animals and birds, with repulsive nestlings, chickens, puppies and kittens mewing pitifully for their mothers. The children lame them and kill them slowly, and no adult stops the sport. They drop kittens and chickens from balconies and run to see what has happened to them. They suspend them by a wing or a leg, and take delight at the fearful little shudders which show that their prisoners are still alive. They roll them in the dust and watch their eyes close, with a heartless-ness that excels that of a cat, and disgraces a human.

In the middle of the seaside strip is a square. Around the square are cafes and other little businesses belonging to friends of the government. There is the police station, under a flag. It has a balcony, from which the chief of police looks over his flock and blows his whistle if they make too much noise in the tavernas. He is a small, fat man with a Hitler moustache and four children; so he knows how to watch over us. I once saw his menacing face silence half the town, after he had been disturbed by a few young peasants who were fooling with a strayed hen.

The road leaves the town through much the same litter of unfinished buildings; patches of bright green garden; faded and scratched grassland; and olive trees. There is a dry river bed, where peasants have thrown bits of plastic. It is amazing, their fascination for the bright, smooth, light feel of plastic, washable and indestructible. It seems they have become unhappy with anything else; they have broken up their ceramic jars into the dust of the roads and thrown their lace-cloths with the manure of their fields.

The road used to dribble on around the headland. But now it ends at a garden wall, belonging to an officer of the fallen dictatorship. The toad once separated his summer villa from the sea; but he extended his garden, without needing the permissions required of the rest of the population. If one struggles over the boulders at the foot of the headland, one can look at the town across the bay, and imagine how beautiful it has been and see what beauty remains — the delectable pattern of white houses with red roofs and dark shutters, sheltered in fruit trees, nestling in a crooked arm of the mountains.

We are strangers here for several days, under the friendly curiosity of the habitues of tavernas, and suffering the rudeness of city-trained clerks in the post office. Rude officials, officials who are pleased to say ‘No’, were bred by the Junta that needed them, and they still infest the offices and bureaus. But before long we are known to those people who really matter in an ordinary stroll through the town: to Adonis the policeman; to Sophocles the butcher who slaughters his goats as they hang from a tree by the main road; to Katerina at the taverna; and to Pericles who sells fish. (Nearly everyone is named after an ancient God or hero. Perhaps that is why they pass a loaf to you with such dignity; no one knows better than they that it is the gift of the Gods.) So after a few days they cease to be rude. In the evenings, they nod to us from their backgammon table; and say ‘Ullo’ in an abbreviated way, as if they were gulping down stones. Everyone who has something to say or to sell has his van or his shop fitted with a megaphone; so every man sounds like the voice of God, if he has a tin of fish or a basket of cucumbers. On several occasions, we are persuaded to buy vegetables, fruit or greens when we are told that tomorrow they will be poisoned because they are going to spray the olive trees. Despite the heat, we close our windows and doors in horror at the poisons we expect to fall from the air. But nothing happens; nobody sees a helicopter. If he has nothing in particular to sell, he amplifies music, from his car, his balcony or his ship. In fact, two tavernas, one at either end of the town, divide the place into two zones of noise. They do not play the songs of Sotiria Bellou, the music of Hadjidakis or Theodorakis. We hear a slimy, half-Turkish whine about crossed love, about ‘kardia mou'(‘my heart’) — ‘bouzouki’, which tourists are supposed to enjoy, and which falls like acid from the air and eats into my quiet.

In the early afternoon, the television sets are switched on; it is as automatic as daylight. The blue, electric flames burn in every room and on every balcony. No taverna by the sea could expect trade without a television set. Peasants come from the little huts in the olive groves, on motorcycles to the tavernas, and watch. There is an old man who leads two sheep on a rope, to watch television at Katerina’s.

It is at this time that I go to dote upon the colours, the whisperings, the smells of the olive groves; the crooked, golden light, matching gilded wheat against green corn and purple and yellow and red flowers; the scents of thyme and of sage and of ligaria, which is like lilac; the flicker of goldfinches or of the scarf or straw hat or sunburnt skin of a peasant; the song of a mild breeze or the deep, slow, throbbing song of a nightingale in the tall reeds by the river bed. I walk along dusty, narrow tracks that wander for miles, here and there dwindling to a mere hairline over the earth, but usually plucking up courage and leading by olive trees and scented bushes and coming upon a lush garden with a bright red pump or a little hut; or upon a little church on a hillock. Very few tracks, fewer than you might imagine, vanish into thickets where one fears there may be snakes. Here and there I come across peasants, men and women plodding in a curious, searching way over the ground, following their sheep, whistling to them sharply, then searching the stubble or the tomatoes or the corn, as if for something that they have lost. They have spent all day with a hoe or a flock of sheep, and it seems a pity that the only company offered to them is that of an Englishman who speaks their language badly.

I like best the two hours whilst the sun sets, and the first hour of starlight. There is a moment that I love most of all, just before the sun finally disappears. Then, half of the sun balances upon the mountain ridge, and the huge mountain is turned into a lake of ultramarine. One stares through the limpid water of what is, in fact, a wall bristling with crags. A magical hour. At this hour even a goat, gilded with light, seems like Pan as it rises out of the corn. If this whispering that I hear in the olive groves is not the murmuring of gods; if that light upon the trees is not the clothing of gods — then what is it? At this hour, I discover what the peasants are perhaps searching for: perhaps they are looking for their gods, who have escaped down a crack in the earth, or into an ant or fox hole.