The name Mani is feminine in gender, and while it has had, in the past, the aloof dignity and self-assurance of a beautiful and austere woman, it has for some years now stood aside more like a wild child of Greece: poor, modest, introspective, and bewildered. All these qualities are reflected in her inhabitants, her barren landscape, and in the unique architecture of her isolated and nearly deserted villages.

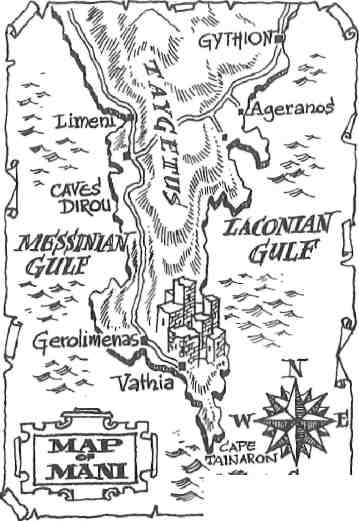

Vathia is among the most extraordinary of these villages, gripping the summit of a desolate, spike-shaped mountain. Like a cluster of cypresses, its houses and towers reach up arrogantly towards the sky, evoking the castles of mythological heroes. The village is set against the abrupt wilderness of the Taygetus range—distinct in character from the Taygetus of the north where green and abundant forests grow in the rich earth of its slopes. These naked and forbidding mountains of the Deep Mani plunge into the sea eight kilometres farther south at Cape Tainaron. They divide the peninsula into two parts. The eastern side has the local name prossiliaki which means that it is exposed to the sunrise. The other side, which is shaded from it, is called aposkieri. This is where Vathia lies, facing west over an unbroken expanse of sea.

The lack of a paved road has been one of the reasons that Vathia, not even noted on some of the maps of the Mani, remains so remote. The dirt road to this eagle’s nest is barely traced over the terrain. As it winds up to the village, a succession of small bays which fret the coast like a border of lace is revealed below. At the entrance to the village, a platoma, or widening in the road, serves as the central square.

On entering this square last August we found three bearded cameramen in bathing suits shouting at an improvised cast that included most of the local population.

‘Don’t put on a tie,’ one cameraman called out. ‘Try to be natural. Be spontaneous!’

A middle-aged man with a weather-beaten face smiled broadly, revealing a row of gold teeth. With great satisfaction, he leaned his chair back against the whitewashed wall behind him. Three old women watched — puzzled and indifferent at the same time. Another old man sat nearby, resting his arms,on his wooden stick. Up on a balcony a young, colourfully dressed woman feeding a little girl became so absorbed in the spectacle below that the child sat with her mouth open, waiting for her food. After a while, the cameramen gathered their equipment, thanked their impromptu cast, got into their car, and disappeared down the dusty road.

We were now the only strangers in Vathia. As soon as we said ‘good afternoon’, we were welcomed. The conversation became friendly, and coffee was prepared and served along with the inevitable Coca-Cola. In the presence of the old people, the mother and daughter, we were confronted by three generations of Maniots. The young mother and her child’ live in Athens, but return to Vathia occasionally because she, or perhaps her husband, was born there. For the child, however, Vathia is just a place to spend a few days away from the city. Except for summer and Easter, Vathia’s only inhabitants are ten old men and women. Since the National Tourist Organization recently announced its decision to restore the town, its inhabitants have adjusted to all sorts of visitors with remarkable speed. Indeed, today, no one in Vathia is surprised by anybody or anything.

‘Are you happy with what is going to happen in Vathia?’ we asked Kyrios Theodoros.

His answer had the resigned uncertainty of a person who had taken no part in the decision.

‘Yes, we are very satisfied. Besides, we have nothing to lose. There are twenty-six towers and more than a hundred houses here. Most of them are in ruins.’

*I gave up my share in a tower with pleasure,’ said Kyrios Panayotis, the old man with the wooden stick. ‘But there are many other owners, seven or eight, and there are two who are not willing to give up theirs.’

The little girl came up and handed Kyrios Panayotis a small white envelope, whose contents were apparently already known to the other villagers.

Open it,’ Kyrios Theodoros said. ‘It must be from the National Tourist Office in Athens. You see,’ he went on, turning to me, ‘the people there are so nice to us. They haven’t forgotten us. Tomorrow is the Assumption of the Virgin, and Kyrios Panayotis is celebrating his name-day. They wish him hronia polla.’

The old man opened the letter slowly with a complacent smile.

I looked away towards the arid slopes of the mountains. A long scar was outlined in the reddish rocks where a new road is being constructed around the southern end of the Mani and which will connect the two existing roads on either coast.

‘What will be done about water?’ I asked. Someone pointed to the top of a nearby hill. ‘There is a spring there, and running water will be available in the village when the necessary installations are completed.’

Knowing that the Mani is a stronghold of the monarchy, I could not resist asking if Vathia had a royalist majority. The answer came without hesitation. ‘Certainly it has! Besides the ten inhabitants there are thirty-seven others who are eligible to vote but who live elsewhere. So, during the last referendum in December, 1974, there were forty-seven votes for the king. We are totally royalist.’

‘Come with me,’ Kyrios Theodores said. I followed him into a ground-floor room in a nearby building, which was a combination storeroom and stable. ‘Do you see that?’ he asked proudly. A reddish, flat stone leaning against the wall was engraved with a crown. Between two crossed olive branches was the word Hellas. ‘It is the work of my son. He is a real artist and a royalist to the bone. Not that there are no communists,’ he continued, ‘but they keep away. There is no place for them here. All the basements in Vathia are full of emblems of crowns. We had to put them out of sight recently.’

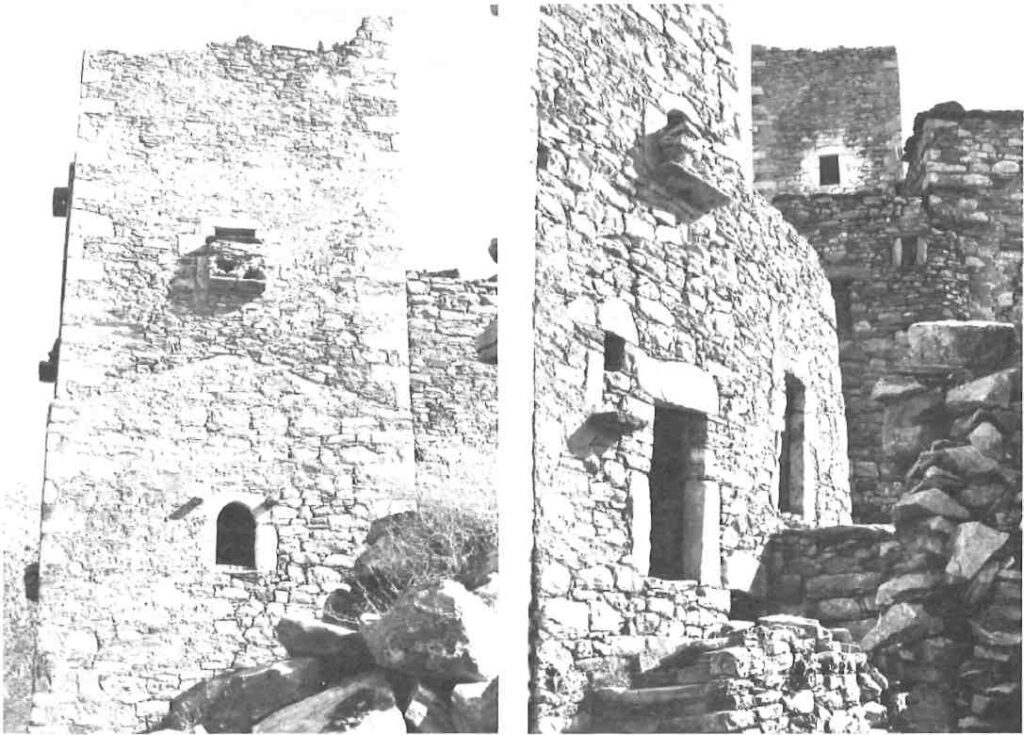

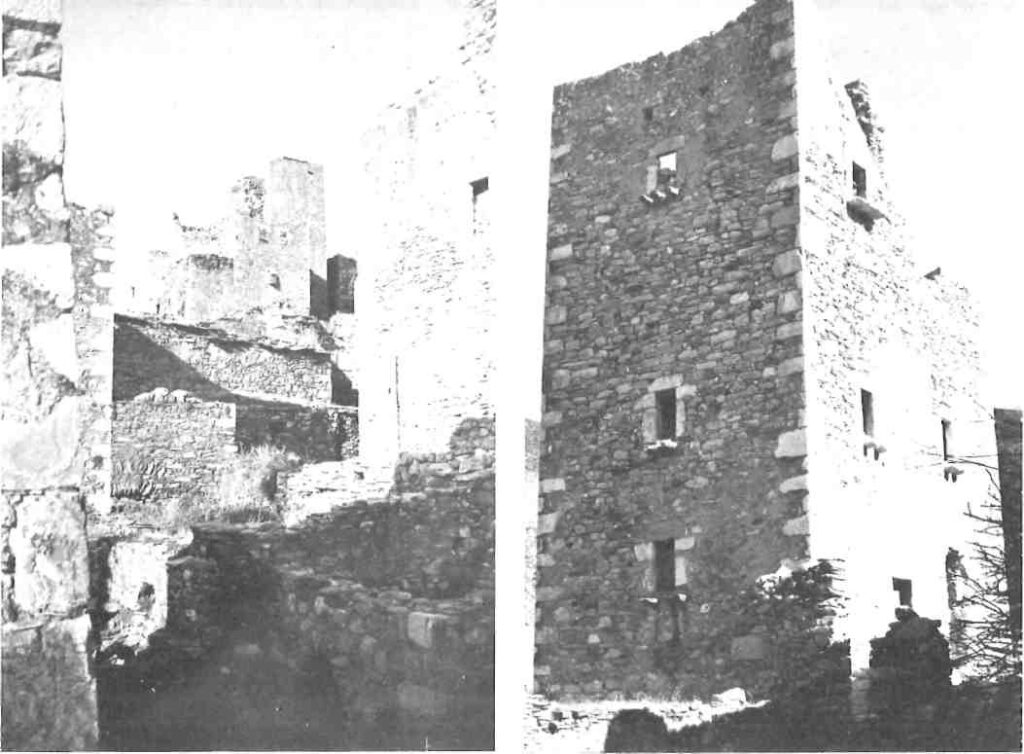

It was late in the afternoon, and we had just enough time to walk around the village before it grew dark. Vathia is a maze of stone buildings and low stone walls. There are courtyards, paths, and open spaces between each tower, which at first glance do not seem to follow any plan. Nevertheless, each tower or house has its own precise limits. Very narrow paths lead through low arcaded doors to totally or half ruined underground rooms full of dung. Looking up, one sees walls studded with tiny windows and embrasures, and crowned by ramparts.

Nothing, not even an animal, disrupts the absolute silence. Among the sun-bleached, dusty rocks, life once in a while appears in the form of a prickly pear, a pomegranate or an almond tree. Far down below, toward the west, the sea sparkles.

We entered a small backyard. Outlined against a high wall of reddish stones was a black silhouette. I found a very old woman who, scorning lambswool, was weaving a carpet out of long bands cut from plastic bags. Her thin, wrinkled hands and face were the only parts of her that were not covered.

‘How are you, Yaya?” I asked, sitting on a nearby rock.

She nodded. Her eyes were like coals. I asked my companion to take a picture of her.

‘You take a photo of me and you will make money out of it, I know,’ she said calmly.

‘Many come now and take pictures of everything. I stay here and watch them.’

‘What is your name, Yaya?’

‘Why do you want to know my name? It will be of no use to you.’

‘Were you born in Vathia, Yaya?’ I persisted.

‘Why do you want to know about me? Yes, I was born and married here in Vathia. And I will die here, too. The only trips I ever took were the two times I went to Piraeus, where I have my only child, my son. But I am alone like the stones. Look at this tower,’ she said, pointing to a three-storey building in front of us.

‘It was given to me by my husband’s relatives, when he was killed in the War of 1912, one year after our marriage. I worked from dawn to night with one worker in order to build the third floor. Now it is in ruins and I live in an underground room.’ She stared at a rotten wooden door held shut with a cord.

‘Are you pleased with what is going on in Vathia now?’ I asked.

‘I’m very old and nothing makes any difference to me anymore. I spent three whole months sick in bed last winter. I almost died, but maybe death has forgotten me. My son comes with his family for a few days every year. That’s all. His wife is a stranger. She is not from the Mani and doesn’t like it. But he is a good son. He sends me a package once in a while.’

This old woman represents the essence of Vathia today: memories and ruins. And there are so many other Vathias in the Mani, forgotten villages with irreplaceable architecture.

When Vathia is restored will it be nothing more than a tourist attraction? Will the people of the next generation appreciate and love what they have never cherished in the past? Who will teach them to love the land where their fathers lived and toiled? Will it be possible to restore the life of this village as well as its buildings? Will those who have left their villages be encouraged to return home?