Sifnoss about twelve miles long and eight miles wide. At dawn and dusk — when they are not lost in the dazzle of light — you can look across the sea to the other Cycladic Islands which were part of the old Minoan civilization based upon Crete: to Paros in the east, to Milos where was found the ‘Venus de Milo’, and to Kimolos in the west. Beyond the cultivated valleys of the islands, where the soil is cherished upon a buried civilization, there is the brutal wilderness, the thorns and thistles and rocks which never have been and which never will be cultivated. In the homely valleys, where people live and work, it is as if it is dry and yellow and shriveled, not because of drought, but through age. My image of the island is of an old woman, feeble, shriveled and dry, who keeps secret the beauty which she once had; and from time to time you catch a twinkle in her eye, because of her secret.

One day, whilst we are sunbathing at Platy Yialo, a boy of about twenty, dressed in a dark suit, clean shirt and tie, and dusty shoes, motorcycles excitedly across the beach. He skids his cycle and lets it fall into the sand and goes to a nearby table where he is given a beer. He has come to invite the owner of the cafe to his wedding, which is on the following day. He must go to every house where he is known — that is, to most houses on this side of the island — and personally invite the inhabitants to his wedding, otherwise they will be offended. Having so much to do, he soon leaves us.

The following afternoon, crowds gather outside the house of the koubara in Eleimonas. She lives in a white house on a mule track, of course. But her home is grander than most. It is old, but with straight walls, that reach half as high again as those of its neighbors. It has baroque windows enscrolled with stucco; they have iron bars, shutters and geraniums; and in the walled garden with its locked wrought-iron gate there is a well, which brings life to luscious fruit trees and brilliant flowers. The koubara is evidently someone to be proud of.

The crowd fills one mile of the narrow mule track that winds along a contour of the hill, by scattered fields and houses, fig trees, a windmill, and the church where the couple are to be married. It threads between the school and the statue of an island poet, until it meets the tarmacked road, where a church is being built. This is where the bridegroom and his friends will be brought on the bus — the taxi has been commandeered for the ship-owner’s wedding, which is on the same day at.the other side of the island.

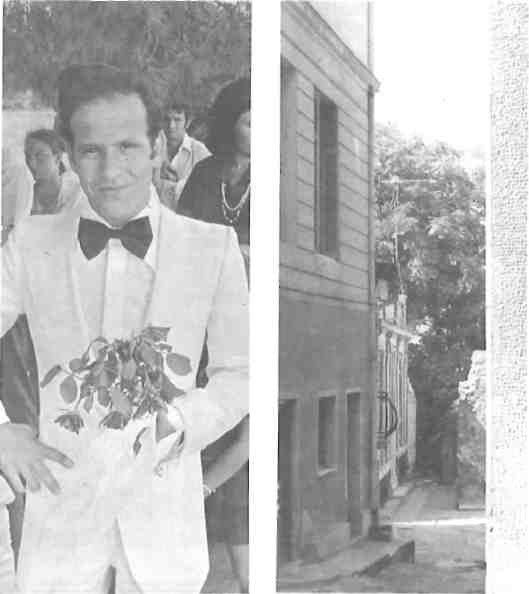

Long before we see it, we hear the bus celebrating with blasts of its horn. There are people who hear the bus, or who imagine they hear it, all the way from the farm near Kamares from which it has fetched the bridegroom. At any rate, people are listening and imagining and suggesting and hushing their neighbors; I myself first hear the bus down in the valley somewhere near to the Square in Apollonia. Then it fades out of sound as it curls round the towns, to suddenly burst into sight and sound boldly over the hilltop near to the half-built church.

The bus — the dark blue, dented, blunt-ended and homely-looking bus on which we ourselves arrived — runs a few yards and stops. A wedding like this is its only break from shunting between the ships at Kamares, the town of Apollonia, and the hotel at Platy Yialo. It is the only noisy thing in the whole sunny landscape, and it is the centre of attention.

A knot of people descend from it. They mass behind the two musicians and the bridegroom and are swallowed down the long gullet of the mule tracks.

We watch it for most of the way. The wedding party disappears behind buildings. It reappears for a moment at a high place by an aloni, where the little white flag tied to a stick seems like part of the ceremony — as if it is the bride’s badge of surrender. Then they sink into a hollow and emerge near to us.

So far as we are able, we press against the banks of the mule track so that they can pass. A mass of people fills the track, rising up its banks to the brim of the walls as if they might spill into the terraces. They are following that tense and firm boy, who slushed his motor cycle into the sand yesterday. With him is an old man with a long black moustache, who plays grief-laden music on a lute, in harmony with a slender boy who plays on a fiddle. The track is stony and crumbling and splattered with mule dirt, the houses they pass are poor, the speck of land on which they live their ancient Minoan life, in the wide pool of the Mediterranean where the warships prowl, is dry and produces little milk or honey; and yet the watching crowd, the guests, the musicians and the bridegroom wear smart, dark suits and white shirts and mail-order printed-cotton dresses. Only their large, incongruous hands and their dark wrinkled skins show how familiar they are with the goat that watches casually from the stubble of a field, or with the hen that panics foolishly on a chimney pot.

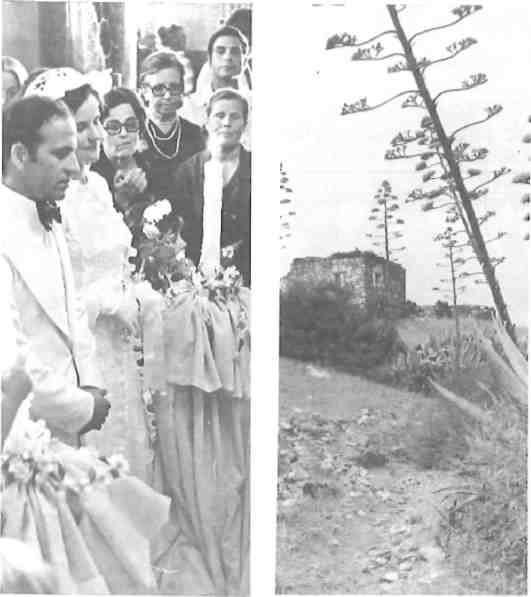

The wedding party goes into the house. After half an hour, they lead out the blushing koubara, to the music of lute and fiddle. The party is framed in tall geraniums within the iron gateway. They lead us all to the church. Like liquid falling into place, we fill up the track behind them. A long and noisy procession jostles in a narrow throat between mountains on the one hand and a sweep to the sea on the other.

There is also a crowd overspilling from the church. But we ourselves go to watch the departure of the bride from her father’s house, which is on the track close to the windmill where the wedding party passed earlier. This lane, too, is packed with spectators; we fight for a place near to the modest gate of the bride’s house.

Inside, there is a sound of music. After a while, the father comes out with his daughter. A frisson passes through the crowd.

The lute player and the fiddle player ceremoniously pick up their instruments and take up positions to lead father and daughter to the church. The father—short, fat, red-faced and eyes damp with tears — struts like a major in an operetta, and is too embarrassed to look directly at the crowd; like a blind man, he seems to be finding his way by some faculty other than sight. His daughter, also tearful, stiffly holds his arm, and they are led by the wild, grief-stricken music.

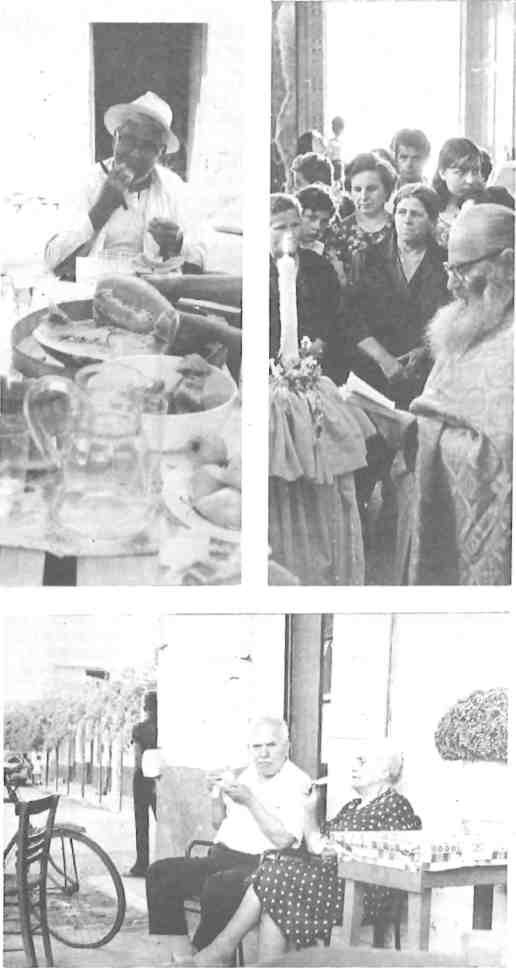

We cannot get into the church. We stay outside with the crowd, and overhear a little of the service: an occasional liturgical shout or muttering and the occasional wave of suspense shivering through the crowd. So, after half an hour, we go home.

But the celebration goes on all night. At about ten o’clock we go to the taverna, where the islanders are celebrating with the two musicians. The cafe is crowded, though no one has yet started to dance. Roya, Ariadne and myself try to creep inconspicuously into a corner — after all, we are sightseers. But immediately someone — I don’t know who — sends beer over to us. Then I recognise him: it is the bride’s father, and it is his duty to give a drink to everyone.

We have been there for only a few minutes when two or three of them clear tables and chairs from the centre of the room. A young man who is obviously proud and confident buys the first tune. He slaps his money on the table before the fiddler, who pretends to ignore it, but plays the asked-for tune, The young man stands erect and cockily, one hand on his hip and the other looped over his head, and dances whilst the others clap and tap their feet. ‘Bravo Kosta!’ they shout. He twirls faster, sinks down to his ankles, almost collapses, rises, clicks his heels and stops. Then he begins again, circling the room whilst the rest of us clap in time to the music. Another man, who has slapped down more coins with the same gesture, joins and then replaces the dancer. After the dancing, an old man sings…

But how can I describe music in words? We return to Ariadne’s house at about two o’clock in the morning, when there is a full moon in the inevitably clear sky.

But not so inevitable that there can’t, occasionally, be a storm. And what a storm: it is an apocalypse. It arrives without intimations, in a weird and savage flurry of dust which rattles and scrapes upon the windows in the dark. This is followed by sheets uf lightning that brighten swathes of the island for long enough to pick out the details.

I go to the little window over the well, and watch. The blue-black grumbling darkness suddenly turns into unbearable light. When the darkness returns, I remember what I have seen… the great leaves of a fig tree pawing the earth; a mule sheltering behind a wall; the monastery glowing on the mountain top above a fall of rock and shingle; or red and green tomatoes, livid swellings upon withered stalks. How strange to see the hard earth with a glistening patina, so that it looks like lead! How strange to see the vegetation darkened with water, and stirring; how strange to feel a moist wind!