The average fisherman today draws his livelihood from the sea in the classic way, using many of the same methods his ancestors used before him. Since the best of his catch is always sold to the restaurants and hotels, the visitor to Greece can usually count on being able to eat a delicious variety of fresh-caught seafood. Even the humblest taverna can put a plateful of lithrinia (gurnard) on the table. These fish, though small and full of bones, are a treat when properly fried in extremely hot oil; they should be crunchy outside and flaky white inside. Washed down with a rough, cold retsina, and buttressed by a salad of just-picked tomatoes and cucumbers, they make a savoury and typically Aegean luncheon.

Lithrinia, along with the innumerable other small fish in Greek waters — barbounia (red mullet), perka (perch), hanos (sea perch), and so on — are usually taken with a hand line. Called kathitiin Greek, this kind of fishing uses shrimp for bait, although minnows also work. Few Greek fishermen ever use a rod and reel; the fish are too tiny and the equipment too expensive. They simply sit in their skiffs, playing out the line and hauling it in, hand over laborious hand, all day long.

The same hand line is used to take the bigger game, such as groupers, sinagrida (gurnet) and vlahos (a kind of grouper or garfish). A larger hook is used and sometimes a different bait — perhaps octopus or squid. But, to call any fish caught in Greece big game is a misnomer. There is an occasional grand-daddy fish of between, say, fifty and a hundred pounds, but the ensnarement of one of these is good reason to declare a local holiday. Anyway, I myself prefer to eat the younger and smaller fish. Between two and five pounds is the ideal size — they are so much more tender and succulent.

‘Throwing the paragadia’ is an interesting and difficult way to fish. The first time I saw the method in action was on a November night, a few years ago, when I went out with two Greek friends, Vassili and Anthimo. Neither was a professional fisherman, but they had fished around Lindos since childhood to provide for the dinner-table and they certainly knew how to prepare the baskets, a three-hour chore. They were also every bit as superstitious as full-time seafaring men. Vassili in particular became quite upset when a man he disliked stopped to watch our preparations. ‘That man is a jinx,’ he muttered. ‘Look at him — he’s putting the evil eye on us. We shouldn’t go out fishing tonight.’ I snickered at this, but later could only conclude that Vassili knew better because that night, after six hours of fishing, we returned with only three pounds of fish.

And what hard and cold work it was! First we chugged down the coast to a site made famous by the film The Guns of Navarone. Remember those towering, steep cliffs, which the Allied raiders were supposed to scale in an attempt to destroy the German gun emplacements? Well, that’s where we went, right in the lee of those spectacular heights, to throw our lines. The sea was only slightly choppy but there was a fairly strong current under the surface which made rowing difficult.

First Vassili placed a wooden float with an oil lamp attached into the sea, and then began to spool out the line as Anthimo bent into the oars. It took almost an hour to place the first line, which sank of its own weight, to the bottom. It was perhaps a thousand yards long, with two – or three – hundred hooks baited with minnows. We were hoping to catch any and all kinds of fish with the paragadia — everything from grouper and gurnet to sea bream and perch, with maybe an odd octopus or two as an added bonus.

It was four in the morning and we were chilled and wet by the time we got home and, considering our poor catch, we were hardly a jolly bunch. We would have been better off eating the shrimps we had bought to use as bait — less strenuous and more economical all around.

Old Yiorgos Kouros, at seventy-seven one of Lindos’s few – remaining, full-time fishermen, had a different view of our experience. He maintained that we had made the mistake of fishing on a dark night. When a fish is caught on a paragadia line he twirls about wildly in an attempt to escape. The thrashing sends out phosphorescence and this in turn attracts marauding big fish such as dogfish, sharks and dolphins which pick the line clean. ‘Next time you throw the paragadia,’ advised Yiorgos, ‘make sure you do it on a moonlit night, when the fish don’t light up as brightly.’

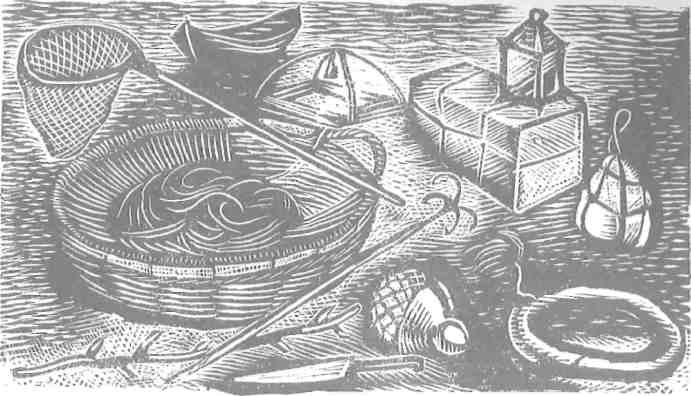

Fishing with nets — ta dihtia — is another common way of fishing in Greece. The fishermen chug out in the early evening, their yellow nets heaped like mounds of saffron, the helmsman standing and often steering with a bare foot on the tiller in a typically insouciant Greek pose. Where the nets are placed depends on many factors: the fisherman’s acumen and instinct, the weather, the current, the time of year. The nets are left out overnight and collected at dawn. All small and big fish in the Greek seas are caught in this way, except for oktopodi (octopus), kalamari (squid) and soupia (cuttlefish), astakos (lobster), and karavida (crawfish in English, la cigale in French).

Fishing with kiourtos — round wire baskets — is another widespread system that produces reasonably large and varied catches. Shrimp are caught in small baskets with a fine mesh, using a smelly paste of flour and sardines as bait. The same bait is used in the larger wider-mouthed baskets to attract groupers, sea bream and vlahos. Skaros, or parrot fish, are caught in the same baskets but with fresh greens as bait; and instead of being left out at night, the baskets are put to work during the daytime.

Crustaceans are occasionally caught with the kiourtos, usually the small-clawed karavida, which is more than an adequate Aegean substitute for lobster. It weighs about two pounds and is packed solid with a firm, white, sweet-tasting meat. In some areas of Greece — notably Halkis and Thessaloniki — the fishermen bring in an even smaller crawfish, about as long and round as an Upmann Corona, which, when prepared over charcoal and served with ouzo, makes an ideal meze.

My favourite way of fishing in Greece is with the syrti. This is a form of trolling. It is best done with two persons, one controlling the outboard and the other the rig. When hunting the small Mediterranean fish called melanouri (black tail) one trolls with a thin nylon line with many tiny hooks baited with shrimp. To catch the bigger and more challenging game like palamida (tunny) and tonnos (tuna) when they come whipping up the coast to spawn, one uses a series of feathered lures. There is nothing quite like running into a swarm of big fellows and feeling them biting one after the other into the hooks. It all happens with bang-bang speed; the motor must be cut immediately and the twitching, straining main line hauled in, taking care lest the fighting fish break away or snarl the smaller lines. Some tuna and palamidain the Mediterranean weigh as much as a hundred pounds, so you can imagine what kind of a tussle it must be to land five or six of these at once.

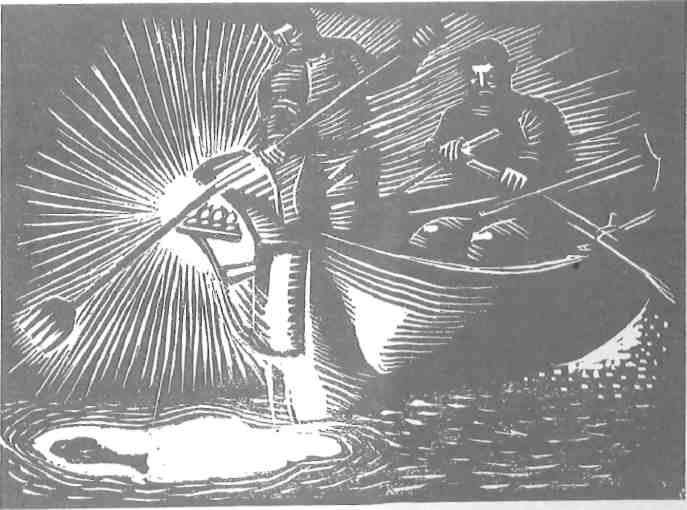

Another preference of mine comes under the generic heading of pirofani— fishing with a light. A pump-up kerosene lantern is the basic piece of equipment in this operation. It is used to pick out sleeping fish, plus inkfish and crustaceans. The light also attracts these species. One glides along slowly in a skiff, poised at the prow with a long-handled harpoon, ready to make a quick deft stab in the shallows. Some Greek fishermen can wield a twelve-foot-long harpoon with the accuracy and speed of a fencer.

Fishing in Greece roughly works out like this: you usually have one chance at catching a ‘big’ fish per day. If you land him, you come home a hero. If you don’t, you’re a bum.

But as with all fishermen, half the fun is talking it over later, boasting about the bounty that got away. The size of the fish, of course, increases in direct ratio to the number of times you tell the story. It also takes much of the pain and frustration out of the day to sit and swap tales in a taverna: in summer over a plate of grilled octopus; in winter over a dish of deep-fried atherina (white bait) which are caught from the shore the day after a storm subsides, using a big net shaped like an upside-down hat.

And like as not there will always be an old fisherman like Yiorgos Kouros around to wave his ouzo glass and shout irrepressibly, ‘Don’t worry, Manos. It doesn’t matter that you didn’t catch anything today. Tomorrow I will take you to a place where there is a thirty-kilo grouper under rock. Tomorrow! I promise you! Just wait and see!’

The woodcuts by Spyros Vassiliou are reproduced from Yiorgos Lefkaditis’s Fishing on the Greek Coast.