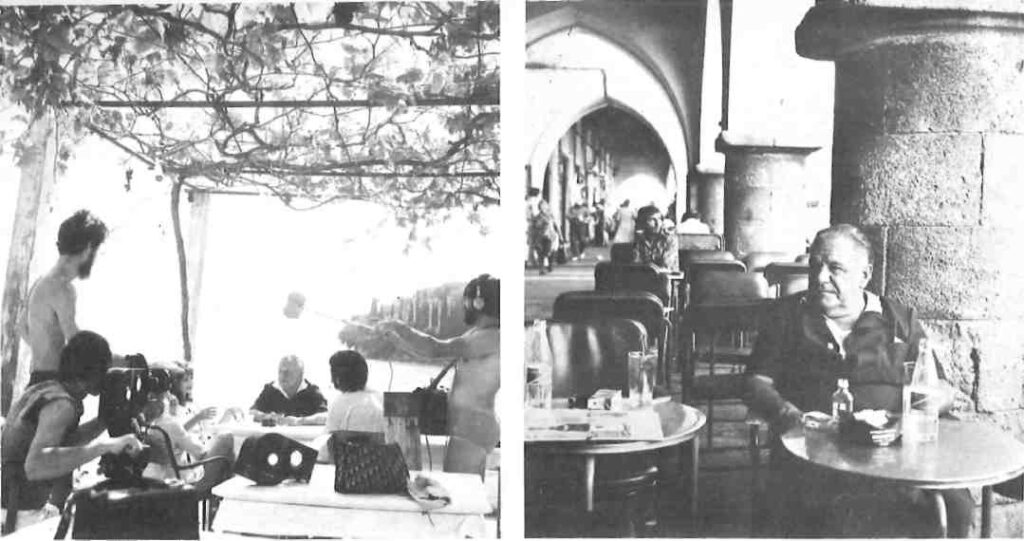

Lawrence Durrell had come to Greece last autumn to do a documentary for the BBC. I found him and the film making crew before a blazing fire in a small inn near Kolonaki Square. Ouzos in hand, they were animatedly discussing a storm their yacht had passed through off Hydra where they had been shooting some of the film. Larry recalled ‘being beaten up by the flying furniture’, as the boat pitched and rolled on the waves and Peter Adam, BBC film director, remarked, ‘How funny Larry looked sitting under a table, imperturbably finishing his drink, while the rest of us peered out from under the furniture.’ Dimitri Papadimos, the producer in Greece, reminisced, ‘Do you remember the Captain’s cake sailing out of the oven across the deck and directly overboard?’

In the ensuing confusion of replenishing drinks, of people coming and going, Larry turned to me and whispered a question. ‘Mumble, mumble … name?’ Thinking he was asking about the pretty, red-haired woman to whom we had both just been introduced, I whispered back, ‘Margaret Livingstone’. It wasn’t until I got home later that evening that I discovered that every fly-leaf of every one of my treasured books was inscribed to ‘Margaret Livingstone’!

When I approached him the next morning, my books once again in hand, he was chagrined and apologetic. Since they were my very-own, well-read and much-battered copies, he carefully cut out with a razor blade all the inscriptions to ‘Margaret Livingstone’, rededicated them correctly and then drew an eye in each book ‘to remove the curse’.

At first sight Lawrence Durrell is unprepossessing. He says of himself, ‘Who is this sturdy farmer type with the idiotic look of eternal hope on his face?’ Physically, he is short and walks with a sort of bandy-legged wobble under a somewhat large tummy untouched by even the hint of a waist line. He has a large head with big, close-set ears; a nose a trifle bulbous; small eyes; once sandy, but now-greying hair.

Verbose, dry-witted, ribald, sensitive, thoughtful, original, he is capable of uttering completely bizarre statements without batting an eyelash, delighting in being a bit of a devil, like a precocious boy waiting for reaction. Indeed, if any of his remarks sound suspiciously like quotations, in toto, from his books, this is the case, for Lawrence Durrell freely plagiarizes himself.

Later, as we sat in the simple Athenian taverna he had suggested, over the Greek food and retsina he savours so much, the talk sparkled with the names of Henry Miller and George Katsimbalis, ‘The Colossus of Maroussi’, writers Patrick Leigh Fermor, Freya Stark, Norman Douglas, Anais Nin, Richard Aldington, D. H. Lawrence, and Theodore Stephanides; poets T. S. Eliot, Sikelianos, Seferis, Elytis, Antoniou and so on and so on. All these have been friends and many have been members of his pareaior some twenty to thirty years. Ί had the most extraordinary stroke of luck for a poet of twenty-one. In fact the more I think of it, the more unreal it seems to me… If you decide to go and sit on a Greek island, you never hope to have the sort of friends that I acquired almost by accident. I used to call most of them my uncles…’

The documentary that had brought Lawrence Durrell back to Greece was a co-production of the BBC, French T.V. and a company in Germany. It was tentatively titled, ‘Lawrence Durrell’s Mediterranean; A Poet’s Evocation of a Landscape’. Although he favoured calling it Islomania — one of his favourite terms — when asked if copyright laws might prevent the use of Marine Venus as a title, he suggested acidly, ‘Why not Marine Venus and Other Animals?’ That his brother Gerald’s books were popular with the general reading public some time before his own has clearly left its mark.

For three weeks Durrell and the film team had shot scenes in Corfu, Poros and Hydra before coming to Athens. Since filming in Cyprus was ‘clearly out of the question both in atmosphere and mood’, Crete, as a substitute, was next on the agenda and the shooting would be completed in Rhodes, in Lindos in particular.

The ninety-minute documentary film, which is scheduled for release on March 13, has been pre-sold to eighteen countries. It coincides with the re-printing of three of Durrell’s island books, Prospero’s Cell, Reflections on a Marine Venus, and Bitter Lemons which describe, respectively, Corfu, Rhodes and Cyprus.

In order to write the script for the proposed documentary, Peter Adam had come to Greece some six months earlier. ‘We wanted,’ he explained, ‘to capture a way of life which is rapidly disappearing.’ He roamed the islands in search of an atmosphere of twenty-five years ago, his homework obviously well-done in regard to Durrell’s three island books. In addition, two more of Durrell’s books were incorporated into the television script: Spirit of Place, a collection of correspondence and es-says, and Blue Thirst (termed Blue Throat by the author), a compilation of lectures given at Californian universities. Together these provided the basis for the selection of places to film. Durrell quotes suitable passages from his books to establish location. With the locations as backdrops, he answers in English, and then French, the questions put to him by Peter Adam, talking about Greece, its history, art, mythology, architecture, language and so on.

Readers of Gerald Durrell’s, My Family and Other Animals will remember that the Durrell family grew up in Corfu. The book describes the experiences of this family of displaced Peterkins living together in an assortment of outrageous villas about the island. ‘More of my brother’s lies!’ says Larry. ‘Actually we couldn’t all have lived in that same villa. We would have killed each other!’ The truth is that Larry, the eldest of the children, then a young adult already married and trying to become a writer, had been the first to go to Corfu. It was only later that his mother, forced by the death of her husband (who had been an engineer in India) to find a cheap place to rear her brood, moved to the island with her other children, Gerald, Leslie and Margaret. Larry and his first wife Nancy lived ‘in a fisherman’s house we took on the bare, craggy northern point of the island, almost in Albania’. In any case, Lawrence Durrell did put his roots down deeply into Greek soil, and spiritually he has never left. ‘There is,’ he says, ‘a very pleasant fancy which is a Far Eastern one; namely, that you have two birthplaces. You have the place where you are really born and then you have a place of predilection where you really wake up to reality … this is my place of predilection.’

Lawrence Durrell’s recollections of Corfu were written years after he had left the island. Indeed, most of his island books were not written in situ. As he says of writing: ‘You need distance. You always start too soon. You think you can use a background immediately, but it never works, fortunately.’

On the eve of World War II, he left Corfu, and after sojourns in Athens and Crete, he sailed, in 1941, on an ancient Australian freighter to Alexandria where he remained during most of the war. After the liberation of Greece, he spent two years on Rhodes and, in the early 1950s, moved on to Belgrade.

Durrell describes the three island books as ‘successive nostalgias’. Ί wrote Prospero’s Cell in Alexandria in the first years of the war. I was so nostalgic for Greece. I also wanted to keep something I could use as a notebook, so my memory wouldn’t go dead on me… I finished Reflections on a Marine Venus in a damp basement … when I was working for the Foreign Office in Belgrade under most miserable conditions.’ (The Dark Labyrinth and Sappho were also written on Rhodes during the two years he was there as an information officer: the first in six weeks because I needed eighty pounds to pay for my divorce … and that’s all they offered me!’ Sappho, he considers, ‘much nicer, much better, much more serious … but The Dark Labyrinth caught on very quickly …’) Bitter Lemons was written after he resigned from the foreign service and had gone to live in England. I had three-quarters finished Justine by then, but I had no money. I’ve always been dogged by children and marriages and money, you see, so I had to stop work on the Quartet and rapidly get an advance on a new book in order to keep on living. That was Bitter Lemons. It began to sell, won the Duff Cooper prize and so on, and for the first time I began to get several hundred pounds a year. A modest, modest income … and then I had to subsidize the rest of the Quartet by writing “Antrobus” books.’ (The Antrobus tales are hilarious accounts of his years in the ‘corpse diplomatique’ described in the three volumes, Esprit de Corps, Stiff Upper Lip and Sauve Qui Peut.) ‘But how can you be a greengrocer who only stocks apples? If you’re a writer you ought to be able to write in several ways. I’ve done millions of words of feature articles, diplomatic dispatches, and all that … when they assemble all the muck that I’ve written, its going to be a dreadful bunch!’

Durrell went on to amplify his remarks regarding children and marriage. ‘I’ve Nancy’s daughter, Penelope, my English daughter, who is tall, straight, blond, fair … and Eve’s, who is my Jewish daughter, all round and lazy, but a very good artist … After the two divorces, I married my very best wife, Claude, an Alexandrian born in Lorraine, who died on New Year’s Day 1967 and after that I was alone so long … Then I married this dear girl, Gislaine, she’s a fashion mannequin in Paris … and also I’ve got this big, gloomy old house to support, too, in Sommieres, France …’

l want to go on record right now as saying I am NOT Gerald Durrell and I do NOT like animals and I shall NEVER like animals!’

Ready for the last day of shooting, high on a hill above the village of Lindos in Rhodes, red-topped roofs below us, Larry sat in his reclining yoga position, with the Acropolis behind. He is dressed in plain blue slacks, slip-on black suede shoes, drooping faded lisle socks, and an undistinguished brown shirt — held together by a single button, a white, mesh shirt underneath — collar and edges frayed, a paper tissue tucked in one breast pocket. He sits for the uncounted audience that will view him. The foil-covered light baffle is in place, the camera in position. The soundman adjusts the microphone around Larry’s body and up under his shirt lapels. He grumbles not-so- sotto voce: ‘They sew you into a microphone like a dummy and then they expect you to be spontaneous and free…’

Silence, as the cocks finally finish crowing, the dogs stop barking, the tourist buses have ‘thank God, quit blowing their horns’. One more wait while a motorcycle roars by, and at last the questions and answers begin:

‘You said once that love is the most important thing in your life. Is it more important than writing?’

A thousand times. Writing is not important.’

‘What one word, if you could have only one word, would you like inscribed on your tombstone?’

‘You go at that in a terribly refined way, and anyway I already have a tombstone, and it says haire, hail and farewell, be happy… and when you see the [quoting from himself again] gravestones of Ancient Greece, it is anonymous haire which attracts you by its simple, obsessive message to the living. It is not the names of the worthy, not the votive reliefs and sepulchre epigrams, but this single word, “Be happy” … it serves as both a farewell and an admonition…’

‘The basic assumption is that the human condition is tragic. Is there any consolation anywhere?’

‘Now that sounds like a Time magazine question. This will be my tenth and last film. After sixty, to keep appearing on film, riding about on donkey-back and talking about Jesus in an authoritative way … I’ll leave it to Malcolm Muggeridge.’

‘Privately, what is the quality you like most in people?’

‘Sexiness, of course. It’s an absolute concomitant with intelligence. The French understand this completely.’

It goes on in this vein. (To the sound man: ‘Apologies, split infinitives again!’) The interview resumes, this time in French. The sun moves, highlighting the tourists toiling across the way. In the small bay, beyond the amphitheatre and roof tops, a microscopic sailboat sits on a ladi thalassa. The Acropolis rears upwards from a rock face, against the blue, blue Mediterranean and bare mountains in the background: ‘Lindos is bold, strident… its beauty is of a scrupulous Aegean order, and perfect in its kind … so that if you half close your eyes, you might imagine that Lindos reflects back the snowy reflections of a passing cloud.’

The filming was over for Lawrence Durrell. In the few days ahead I accompanied him on his shopping circuit about Athens, sat with him in Orphanides’s ouzeri, taping endless conversations, over endless ouzos, met the ‘Colossus’ and ‘Paddy’ (Patrick Leigh Fermor) and Captain Antoniou, and, at the end, put a weary but gratified Lawrence Durrell aboard his plane to France.

Ί shall never return, you know, it’s all so different now, in Greece … but then … maybe in the spring …’