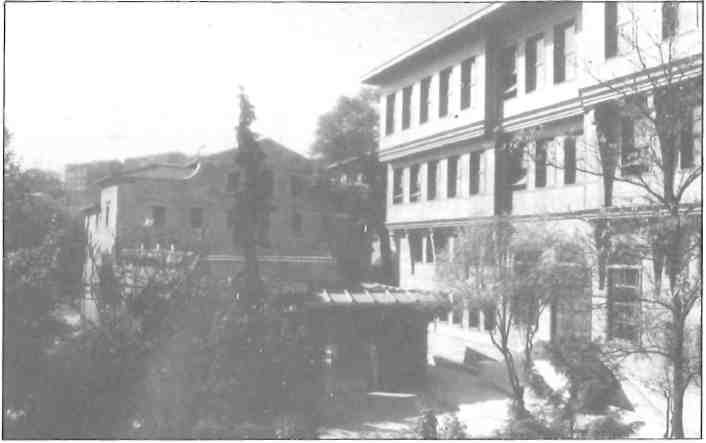

In the shabby, long-beleaguered patriarchate of Constantinople a new spirit of cautious optimism prevails: its normally quiet courtyard – a place of martyrdom – reverberates these days to nothing more threatening than the unaccustomed bustle of restoration and rebuilding work. The slight but nevertheless perceptible thaw in its chilly relations with the Turkish authorities is all the more remarkable considering that a little over two decades ago its very existence was endangered.

Many factors have led to the recent rapprochement, and kudos must go in part to reasonable men of goodwill; clerics like the Pope who paid a highly publicized conciliatory call on the Patriarch in an effort to heal the centuries-old breach between the churches of Rome and Constantinople, and statesmen such as ex-US president, Jimmy Carter, who expressed concern over the neglected state of the patriarchate during his visit there several years ago.

According to the spokesman for the church in Athens, Andreas Papandreou and Turgut Ozal also contributed. However much the “Spirit of Davos” may appear a public relations exercise, it did at least lead to Ozal’s meeting the Ecumenical Patriarch for the first time, and a certain amount of positive thinking, as opposed to sabre rattling, percolated down through various levels. Mayor Dalan of Constantinople/Istanbul (deposed in elections earlier this year) lent a sympathetic ear, and ministers, both Greek and Turkish, met to shed some light, albeit faint, on this dark corner of mutual distrust.

Private individuals have also played an influential role, many offering both money and personal assistance in the hope of ameliorating conditions in the historical patriarchate which has existed for over one and a half millennia as a focus for Christian Orthodoxy. One such man is the industrialist Panayiotis Angelopoulos who, during the official visit of Patriarch Demetrios to Athens in November 1987, donated six million dollars for the rebuilding of the patriarchal offices and reception rooms destroyed by fire in 1941. Building permission, long withheld, was soon granted and the large timber wing, a replica of the original, is almost completed, awaiting only interior decoration. Mr Angelopoulos, presently abroad, was unavailable for comment, but in a previous statement said “…within 24 hours we decided on this gesture and acted, without publicity as is our custom. The Patriarch did not solicit it nor were we pressured into it by any other source.

Dr Achilles Kanellopoulos, Dean of Athens’ Southeastern College, a devoted friend of the Patriarch, whose signed photograph hangs in the main office of the college’s Kifissia campus, believes that personal contact at all levels produces more lasting success in breaking down barriers of mutual suspicion between the two nations than much-publicized political talks. The college has quietly been running a limited scholarship scheme for needy Orthodox youths for the past six years and the dean encourages student exchange visits between Athens and Constantinople whenever possible. The college has also donated a computer system to the patriarchate and is training the personnel involved; this will update facilities and, it is hoped, ease the workload in its offices, secretariat and library, which is considerable.

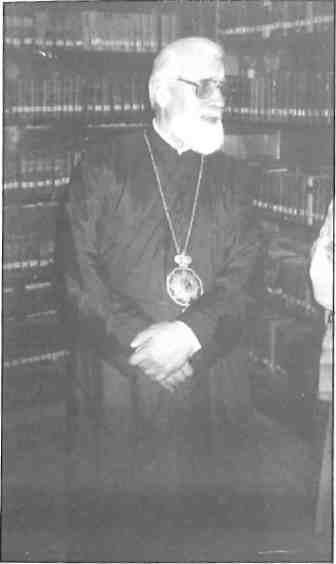

Surprisingly, the Patriarch, after centuries of balancing on the high wire of local politics, still has jurisdiction over Orthodox churches of the diaspora from America to New Zealand, Australia to Western Europe, as well as those of Crete, Turkey, the Dodecanese islands and Mount Athos. Archbishops in those countries are selected, in part, by him, in counsel with his 12-man synod. Unlike the Pope in Rome, however, the Patriarch’s power is not absolute and the Orthodox Church is not centralized: the Patriarch does not have the right to interfere in the affairs of autocephalic churches with their own patriarchs, such as those in the Soviet Union. But since the final schism, or split, between the churches of the East and West in the 11th century, he is held in high esteem and embodies a marked spiritual preeminence.

Since Constantinople was conquered by the Turks 500 years ago and the original patriarchate (founded in AD 381) adjoining the magnificent church of Ayia Sophia became part of a mosque, the Orthodox premises have been moved five times. The present site, dating from 1601, overlooks the now run-down Greek district of the Phanar and the waters of The Golden Horn; its church of St. George, once part of a Byzantine convent, has suffered throughout the years, mainly from the twin curses of Constantinople – fire and earthquake – and has been much altered. Restoration work on its facade is now completed and a team of American architects is presently working on plans to renovate its somewhat drab and dingy interior.

Despite the historical meeting between the Pope and the Ecumenical Patriarch some years ago and the generally friendly spirit prevailing between the eastern and western churches, the latter appears to maintain its centuries-old disinterest in the sad plight of the patriarchate. It is left to Orthodox leaders around the world, such as Archbishop lakovos of North and South America, and laymen to exert whatever influence they can in whatever way possible.

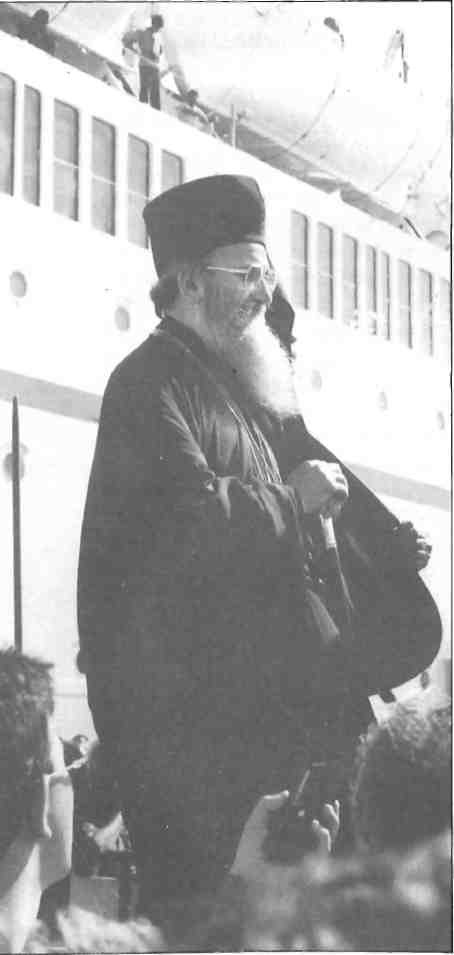

The fact that the Patriarch, the only member of the patriarchate allowed to wear ecclesiastical robes, and his synod must, by law, be Turkish citizens is causing problems of continuity. Candidates are, of necessity, drawn from the fast-dwindling Orthodox communities of Turkey whose numbers, willingly or not, diminish every year. Demetrios, the present patriarch, was formerly the Metropolitan of the islands of Imbros and Tenedos whose Christian population has been reduced to several hundred, predominantly old people. Even in Constantinople itself the problem is acute. The renowned Greek high school, Megali ton Yenous, has only 20 pupils, and the venerable theological college on the off-shore island of Halkis has none; there are not enough Orthodox Christians in the city to provide congregations for all the churches, some of which only function one day a year in order to prevent their being officially requisitioned for other uses. Constantinople, the first city founded with Christianity as its official creed, dazzled the barbarian hordes of the early Middle Ages with the splendor of its magnificent churches; its influence on the first decisive ecumenical councils helped mould the form of emerging Christian Europe. There is surely a case for placing the patriarchate, as an historical center of Orthodox Christianity, under international protection and according its patriarch diplomatic status, which would enable ecclesiastics of other nationalities to fill the office, thereby ensuring its perpetuation.