Mimica, the hostess and wife of a prominent shipowner, greeted her friends as they came in with a laughing “hello, comrades” and added “I suppose that’s what we must call each other now that we’re living in a socialist state.”

Fifica, the wife of a cement manufacturer, was not amused. “You can well be flippant,” she said. “Andreas can’t touch your ships but Lord knows what’s going to happen to our cement factory.”

“Well,, whatever happens, you can’t be worse off than poor Titica here, whose husband is no longer undersecretary of whatever he was and who wasn’t even elected to parliament,” Mimica replied.

“Really, Titica,” she went on, turning to the elegant lady who was dealing the cards, “how did Toto take it?”

“Oh, Toto is suicidal all right. He was looking for that cyanide pill the British gave him when he was a mountain guerrilla with Zervas during the German occupation, but he couldn’t find it so he went off on a two-week package tour to the Bahamas. I suspect he took his mistress with him but I don’t mind. He’s been impossible to live with these last few days and if that little slut can put up with it, more power to her!”

The other ladies smiled behind their cards. They all knew about Toto’s affair with the pretty little manicurist at his club, but this was the first time his wife had admitted that she also knew and the revelation would provide grh.t to their telephonic gossip mills for days.

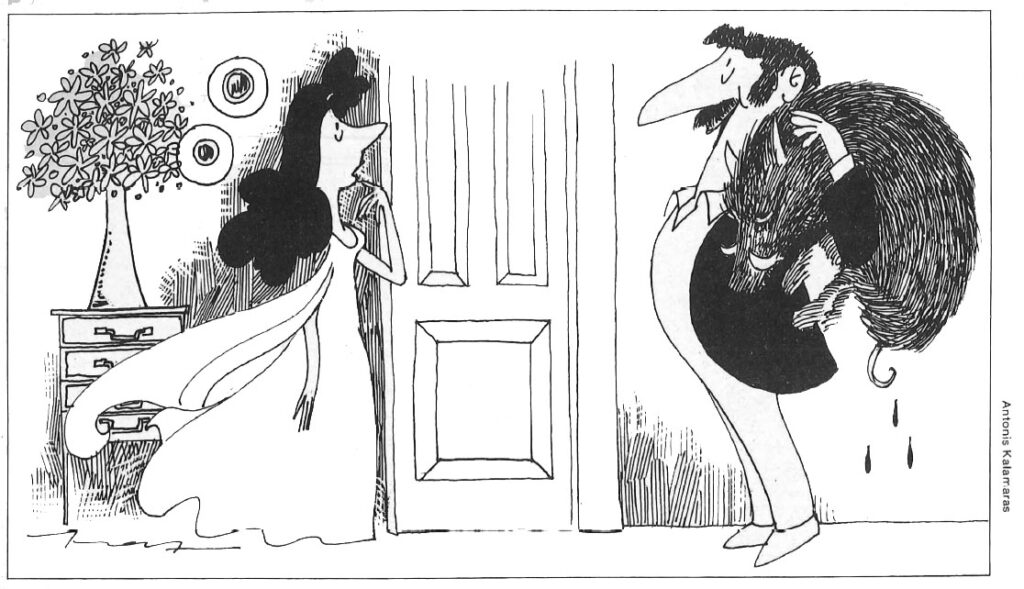

“Anyway,” Titica went on, “I’m glad he’s out of things at last. I couldn’t bear those awful people who used to come down from his constituency and pester him for favors. I had the most awful experience with one of them only a month ago. It was almost midnight when the doorbell rang. It was the maid’s night out and Toto was away on a parliamentary junket in Paris, so I answered the door myself. There was a burly man standing there with a load on his shoulder. Next thing I knew he had dumped the bleeding carcass of a wild boar at my feet. I nearly had a fit! ‘Who are you, what do you want and what is this, this thing here?’ I asked when I had recovered my breath. He turned out to be a leading stalwart in my husband’s party machine in his north-eastern department. I had to let him in and, over a cup of coffee, he explained to me that his son was doing his military service and had been assigned to a desk job in Athens. He wanted my husband to use his influence to have him transferred to the north-eastern border where he would be closer to home. ‘That’s a change,’ I thought to myself. ‘It’s usually the other way around with these conscripts.’

The wild boar was his idea of a fair exchange for the favor. ‘Hang it up for a few days and then cook it slowly in wine,’ he said, ‘it will make an excellent meze.’ The idea of having to live with that horrid beast with its glazed eyes and gl1astly yellow tusks for more than two minutes was an appalling thought, but I had to thank him pr9fusely and promise my husband would do his best for his son. Well, no more of that for the next four years, at least!”

The other ladies laughed and then Lilica spoke up. As the wife of a man who had begun his career as a corner grocer and built his business up into a chain of supermarkets, she had had to struggle for social acceptance and had done so by giving the most lavish parties in Athens to which all the leading lights of the establishment were invited and with most of whom she was on a first name basis.

“What are we to do with all these new ministers and undersecretaries!” she cried. “Did you see their pictures in the papers?”

Mimica said: ” I’ve never seen so many fierce moustaches and long curls in my life! Where on earth did Andreas find them all?”

“I don’t know any of them,” Lilica said disconsolately, “and I have absolutely no idea whom I’m going to ask to my next party.”

“Don’t you worry, my dear,” Titica said grimly, “by the time Andreas has finished taxing you, you won’t have any money for parties, you mark my words.”

A curtain of gloom fell over the ladies at this point until Mimica had a sudden thought.

“We all know Melina,” she said brightly.

“The papers certainly have been making a fuss over her, haven’t they,” Fifica observed, “but they’ve certainly got her age wrong. Can you imagine? Some say she’s fifty-six and others fifty-eight, when I know for a fact she’ll never see sixty again. I was a little girl in Kolonaki when she was already a jeune demoiselle and I don’t mind admitting I shall be fifty six next month”.

Lilica, who was rather sensitive about her own age and didn’t like the turn. the conversation was taking, interrupted to say:

“Well, you must admit that however old she is, she’s still a very attractive woman and very dynamic too.”

“That’s true,” Mirnica admitted, “and certainly an improvement on all those moustaches.”

“Did you see Andreas’ interview on ABC television? I thought he handled himself very well in that,” Fifica remarked. “Spoke excellent English, too, .which is more than I can say for any of his predecessors. He’s cut his hair short, too, and wears a tie. I was most impressed.”

“Why don’t you invite him to your next party,” Mimica said to Lilica, “and perhaps you can persuade him not to nationalize Fifica’s cement factory.”

Fifica looked up at Mimica and when she saw the smile cin her lips she said , with annoyance, “Now don’t make jokes about our predicament. Don’t listen to her, Lilica.”

But Lilica was looking thoughtful. “You know,” she said, “somebody told me the other day that a lovely house right next to the Papandreou estate in Ekali will be going up for sale soon. Perhaps I’ll ask my husband to look into it. We’ve been thinking of moving up to Ekali for months now. You know, the smog in Athens and all that.”