This speculation appeared in leading articles in newspapers and in the thoughtful analyses of pundits on radio stations and television screens throughout the world.

In this country, however, such interpretations as were made in the mass media went largely ignored.

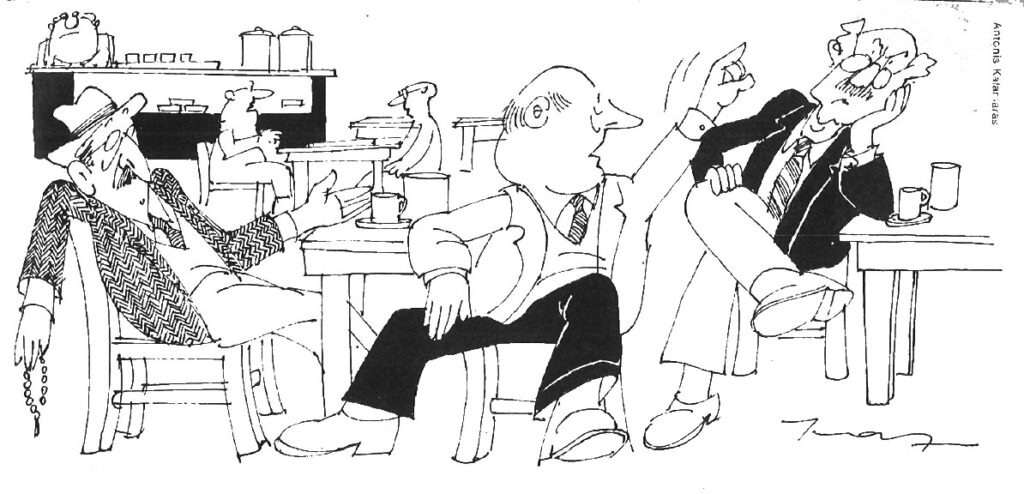

Every Greek had his own opinion and was vastly interested in the opinion of his fellow Greek. The discussions took place, as always, in the ‘kafeneion’; that unique establishment which is the real parUament for Greeks in all walks of life, from Kolonaki to the remotest village in the Zagorohoria.

Typical of these discussions was one that took place on November 6 in the ‘Kafeneion To Anthos Tis Ipirou’ (The Flower of Epirus) in a working class district of Athens.

As they did every morning of their lives, the pensioners who patronized the ‘kafeneion’ from about 9 a.m. until lunchtime, sipped noisily at the single cup of coffee that was to last them three hours, pensively clicked their worry beads and began talking about the event of the day.

“Astounding,” said Anestis Grammatosimos, a retired mailman.

“Incredible,” agreed Babis Economou, who had just completed thirty-five years of government service as a janitor in the Ministry of Finance.

“I never expected it,” added Apostolos Batsos, a retired police sergeant. “But it shows there is a definite swing to the right in world politics, and a very welcome change that is, too.”

Another of the ‘kafeneion’ patrons glared at him. It was Nicolaki Pasoktzis, a retired schoolteacher who was a confirmed socialist and well-known to the ‘Flower of Epirus’ crowd for his left-leaning views. He said:

“Just you wait until our elections next year and you’ll see what will happen to the right in this country!”

Anestis recognized the signs that would lead to an interminable vociferous altercation between Batsos and Pasoktzis on Greek politics and broke in quickly by saying:

“What I can’t understand is how Reagan was able to get eight million votes more than Carter?”

Babis took on the air of authority vested in him by his long service in the Ministry of Finance and declared:

“It’s very simple. The Greek-Americans gave him his victory.”

The others looked at him with interest.

“How do you work that out?” Anestis asked.

“As you know,” Babis replied. “Carter won the Greek-American vote by promising to solve the Cyprus question in his campaign pledges in 1976 and what did he do? When the Turks threatened to close down their American bases, he immediately lifted the arms embargo, kept the Turks happy and left them with no reason to do anything about removing their troops from Cyprus. So when the Greek-Americans realized this, word went out that it was thumbs down on Carter in this election and, naturally, thumbs up on Reagan. That’s how I work it out”.

“Wait a minute, wait a minute.” Nicolaki protested. “There are only three million Greek-Americans in the United States. How does that give him eight million votes?”

Babis looked at him pityingly. “It’s obvious, my dear fellow, that if three million Greek-Americans took the trouble to convince two fellow-Americans to vote with them, you have nine million votes from the Greek side. It stands to reason, doesn’t it? And if one million of the six million friends changed their minds at the last moment, that still leaves eight million, doesn’t it?

The others nodded. They admired the subtlety of an argument that had not occurred to them.

“So Reagan owes Greece an immense debt of gratitude,” Batsos remarked, “and also being a Republican and a right-winger, he will obviously want to help our own rightwing government by putting pressure on the Turks to pull out of Cyprus before our own elections next year.”

“Rubbish,” Nicolaki Pasoktzis exclaimed. “Absolute rubbish. Nothing Reagan can do will prevent our Andreas from winning the next elections!”

“And in that case,” Batsos argued, “what sort of relationship can there be between a right-wing American President and a socialist Prime Minister in our country? Particularly if Andreas carries out his threat to pull us out of NATO? You saw what happened when we went back into NATO? Rallis said the other day that more money would be spent on welfare and education next year because we wouldn’t have to spend so much of our own money in buying arms.”

“Well, Reagan comes from California and Andreas used to teach there at the University, didn’t he?”

Anestis the mailman observed, trying to be conciliatory.

“That is immaterial,” Batsos snapped. “We will be judged by the Americans according to our political orientation. If we have a right-wing government, they will give us their full support. If we have a socialist government, all we can expect is a kick in the pants.”

“Anyway,” Babis pointed out, “we have a right-wing President in Karamanlis and he will never let Andreas do anything foolish if he does become Prime Minister next year.”

“But for how long?” Anestis asked. “What happens if both Reagan and Andreas are elected to a second term and Karamanlis’ term expires in the meantime?”

Nicolaki was quick to reply at this point. “When that happens,” he said, “we elect Melina Mercouri as our next President and, both of them being or having been practitioners of the Thespian art, they will get on like a house afire. Greece will never have anything to worry about.”