It is a rare breed and the few bodies who make it up manage to appear at all the embassies in Athens which celebrate their national day once a year; all the functions thrown by the various airlines to mark the acquisition of some super-duper mammoth jet; all the government receptions in honour of some visiting dignitary and all the cocktail parties held by companies, institutions and professional associations in the better-known Athens hotels.

One never knows what exactly these people do for a living, even after one has been introduced to them and spoken to them for a while. But one gathers the impression that by going to these parties, they have probably managed to solve the problem of eating at night and, at the same time, alleviate the tedium of a very boring existence.

I saw Costaki at a recent embassy reception, dressed to the nines as always, a half-empty glass of scotch and soda — a permanent fixture — in his left hand, standing by the buffet and casting a jaundiced eye over a mouth-watering array of canapes and other tidbits with a rather constipated expression on his face.

“Hallo, Costaki,” I said. “You’re looking rather constipated tonight, what’s the matter?”

“Oh, is it showing? Well, if you must know, I’m always constipated. Always have been and probably always will be.’ It runs in my family — hence the name,” he said.

“I should imagine it’s all this cocktail party food you eat. Not much roughage in it, you know,” I pointed out.

“True, true,” he said, “but it would probably keep us going for a few days if we were trapped here and held hostage.”

“Trapped? Held hostage?” I exclaimed, “surely you don’t think something like that could happen in Athens?”

Costaki smiled knowingly and caught me by the arm. “Come,” he said, “let me show you something.”

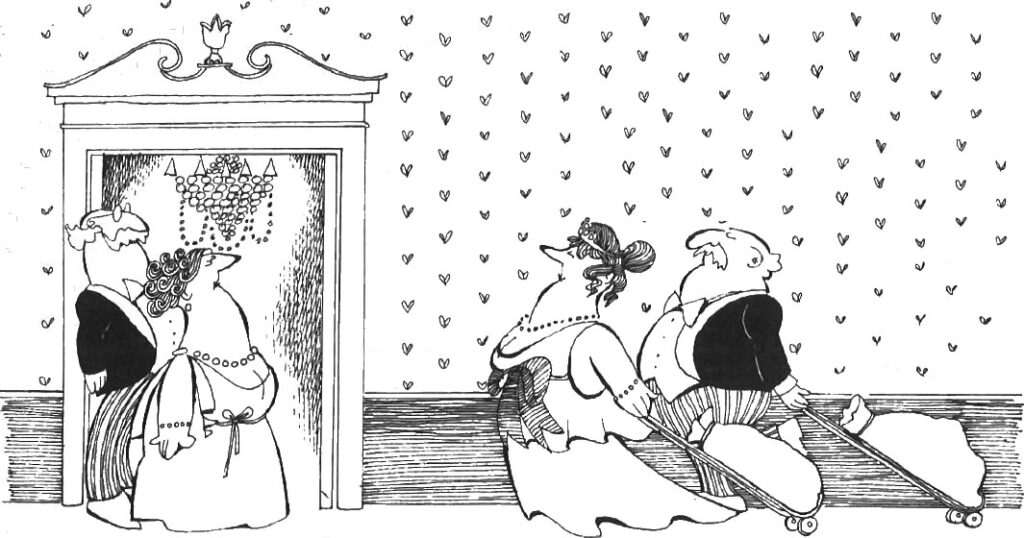

He led me to the cloakroom of the embassy where a pert young maidservant was hanging up the coats of late arrivals and flashing a toothy smile as she handed them a numbered marker.

I saw a number of overnight bags hanging among the coats and Costaki pointed at them with a triumphant smile on his face.

“As you can see,” he said, “some of the guests have come prepared.”

I was horrified. “They don’t really think we’re going to be attacked and held hostage by terrorists, do they?” I protested.

Costaki shrugged. “One never knows what may happen these days. We live in perilous times and diplomats seem to be getting the worst of it in most parts of the world. An occupational hazard, I suppose.”

“And what do they carry in those bags, guns?” I asked.

“Oh, no. Nothing like that,” Costaki said. “I was at a reception at another embassy yesterday and while the cloakroom attendant was on some errand I managed to peek into some of the bags. A pair of pyjamas, a couple of clean shirts and drawers, socks, shaving kit — that sort of thing. Some of them also had a few goodies in them. A jar of peanut butter — probably belonged to somebody from the American Embassy — a handful of Mars bars in another bag, a packet of pumpernickel in yet another and so on. Quite a bit of reading matter too, keep-fit manuals, bridge manuals, sex manuals and some fiction.”

“You should be a customs inspector,” I said. “Didn’t you find any drugs?”

“Nothing to speak of. Some sleeping tablets, that’s all. But the most important drug of all I have here in my pocket,” Costaki said, patting the side of his well-tailored jacket.

I was intrigued. “Tell me more,” I said.

We wandered back to the buffet and as Costaki nibbled gingerly on a hot meatball he told me this extraordinary story.

“A couple of years ago I was invited by the ambassador of the West African Republic of Merengue, who was going on home leave, to stay with him for a couple of weeks at his lovely home at Pot-au-Feu, the capital of Merengue. Naturally, I accepted the invitation, never having been to West Africa before and being familiar with the ambassador’s reputation as a gracious and generous host.

“Life in Merengue, aside from the heat and humidity, the mosquitoes and the monkeys, was very much as it is in Athens, with a never-ceasing round of receptions and cocktail parties. As you can imagine, I was in my element and I even found, to my delight, that some of the more exotic features of Merenguan cuisine were actually relieving my constipation. To my even greater delight, I found that there was one drug store in Merengue that stocked Brook-lax, my favourite laxative.

“Well, to cut a long story short, one day, while we were being entertained at one of the western embassies in Pot-au-Feu, the place was suddenly attacked by a gang of armed ruffians. They called themselves the People’s Army for the Liberation of Merengue’s Oppressed, Lowly, Inferior and Victimised Elements or PALMOLIVE for short, and they herded us into the great ballroom of the embassy. There, their leader harangued us for two hours on the shameless way we were living high off the hog while ninety percent of the Merengue’s population had to live off bananas and coconuts.

“He was a tall, wild-looking creature, with a greedy look in his eyes and every time he wanted to emphasize a point he would say: “While you people have the good fortune to eat like this,” at which point he would gather up a handful of canapes and stuff them in his mouth, “the poor babies of Merengue are starved of proteins and all the body-building foods so strongly recom-mended by Dr. Spock and other distinguished doctors and scientists.” By the end of his speech the buffet had been cleaned out and he staggered off, belching loudly and giving instructions to two of his henchmen to keep their guns trained on us and shoot any of us who made a false move.

“He then went up to the second floor of the embassy and began shouting his demands to the police and Merenguan army units who had surrounded the building in the meanwhile.

“We could not hear these demands very well from the ballroom but we later heard he had asked for a hundred million dollars in small bills and a fleet of jumbo jets to take him and his men and about 2,000 political prisoners held in Merengue jails to Havana.

“He gave the authorities twenty-four hours to comply with his demands and theatened to roast us all over a slow fire if they were not met. We were naturally most alarmed by the whole situation and one of the more intrepid diplomats even suggested we should try and rush the terrorists. After all, there were about thirty of us and only two men guarding us. We did not know how many more there were in the building but we reckoned, from the number we had seen during the original assault, that there must be about eight more.

“But we were completely unarmed and somebody was sure to get killed even if we finally succeeded in overpowering them. So we abandoned the idea and settled down for the night on the ballroom floor.

“A couple of hours later, I saw one of the guards rummaging among the empty plates on the buffet table. He was obviously hungry and was cursing his leader under his breath for having cleaned out all the goodies. An idea struck me. I had bought five packets of Brooklax from the chemist’s earlier that evening and they were in my pocket. As you know, Brooklax looks and tastes like chocolate. And there are eighteen double squares in each packet.

“With an ingratiating smile, I offered a handful of foil-wrapped chocolates to the guard. He took them, unwrapped one and nibbled at it suspiciously. Then his eyes brightened and he gobbled them all. I gave some more to his friend and then offered the rest of my supply, suggesting they share it with their friends in other parts of the building.

“Six hours later it was all over. We all calmly walked out of the building as the police and army rushed in to arrest ten very ill and very miserable terrorists, all locked up in the embassy toilets.”

I laughed and said: “Costaki, I think you’re putting me on. I don’t believe a word of your outrageous story.”

“You don’t?” Costaki asked, with a look of pained surprise. “All right, next time you come home I’ll show you the decoration I received from the President of Merengue himself.”

“And what was that?” I asked.

“Why, the Grand Order of the Chain and Handle, of course — the country’s highest award!”