It instructs them to devote at least one hour per week to lecturing their young charges on how to be polite to tourists and how to make their stay in this country even more pleasant than it normally is.

So when the schools opened in mid-September Sotiris Sfaliaras, headmaster of the State Demotic School at Kato Vothros (a prosperous community in the Piraeus-Aegaleo area), had prepared his first lecture on the subject. Being of a somewhat poetic nature, Mr. Sfaliaras began thus:

“You will all have noticed that every summer we are visited by large numbers of people who come from abroad. They come like swarms of migratory birds from the north. Fleeing the cold and seeking the warm sun, the beautiful blue sky and the crystal-clear sea, they come to our country for a few weeks of leisure and relaxation and to gather new strength to face the rigours of another icy winter in their homeland.”

Mr. Sfaliaras paused, rather pleased with his introduction, and ran his eye over the class to gauge its effect. Mimis Mikroulis, a bright-eyed twelve-year-old, had his hand up. Mr. Sfaliaras sighed. Young Mikroulis could be very’ troublesome at times, but since his father was the only sewage disposal contractor in Kato Vothros and since Mr. Sfaliaras had to empty the septic pit in his small villa on the outskirts of the community at least once a fortnight, Mr. Sfaliaras often had to restrain a very strong inclination to cuff Mikroulis smartly on the ear.

“What is it, Mimi?” he asked, patiently.

“I didn’t see any visitors from abroad in Kato Vothros this summer,” the boy said.

“And why should you expect to see visitors in Kato Vothros,” the teacher replied, “when we have no beach and no ancient ruins that might interest them?”

“We have one ancient ruin,” the boy said.

Mr. Sfaliaras searched his memory quickly for any antiquity that might exist in Kato Vothros but he drew a blank. “And what is that?” he asked.

“Kyra Eleni,” Mikroulis said and the class broke out in raucous laughter.

Mr. Sfaliaras sighed again. Kyra Eleni was a wealthy, seventy – year – old woman with a coquettish disposition who lived in a large house in Kato Vothros. She claimed to be the widow of a shipowner, but it was common knowledge that she was a retired bordello madam.

Mr. Sfaliaras decided to ignore the interruption. He would be needing the services of Mr. Mikroulis senior very soon.

“However,” he went on, “the tourists do not come here only to enjoy the physical features of our country, but to visit as well the monuments of our great cultural heritage which is the root of their own culture as well.”

Mikroulis’ hand was up again.

Mr. Sfaliaras sighed a third time and looked enquiringly at the boy.

“Sir, is it true that tourists bathe naked on our beaches?” Mikroulis asked. A titter ran through the class. Mr. Sfaliaras was beginning to get angry.

“That is not possible, my boy,” he said sternly, “since there are strict laws in this country against offending public decency. Wherever did you get that idea?”

Another boy broke in: “It’s true, sir, it’s true. My big brother is a steward on one of the cruise ships and he told me there are two beaches on Mykonos where people bathe naked, one for ordinary people and another for queers. He said he saw a whole row of white bottoms on the beach and that he had never been photographed so much before in his life.” (Ed. Note: There is a popular saying in Greek that when someone accidentally exposes his bottom to you he is ‘taking your photograph’.) There was a roar of laughter from the class and Mr. Sfaliaras had great difficulty in restoring order. When he finally did so, he noticed that young Dimitri Spasilas, a serious bespectacled boy who was always top of his class, had his hand up.

“Yes, Dimitri?” he said.

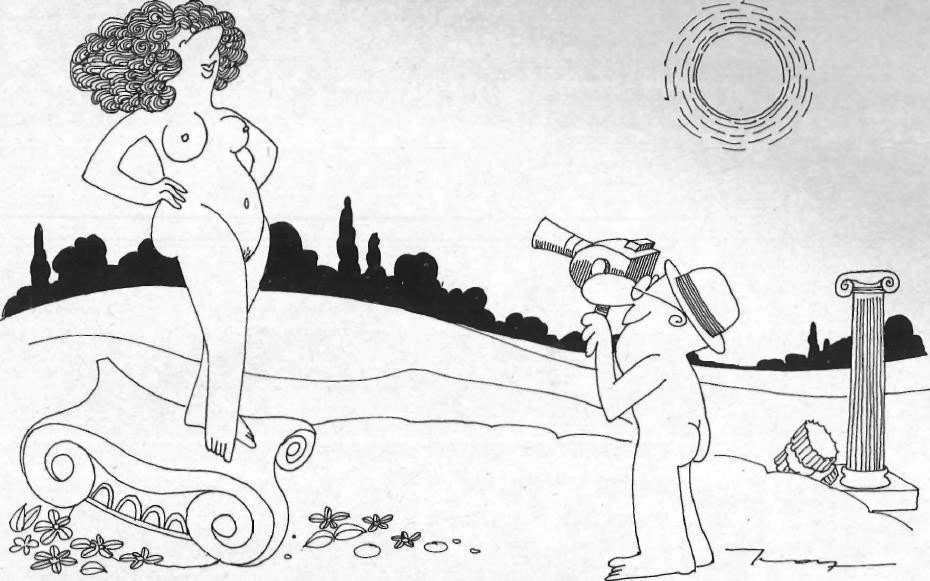

“Sir, I spent a few days at my uncle’s house in Skopelos during the summer holidays and I went for a long walk, collecting specimens of wild plants for my botanical collection. At one point, I came to a rocky height and looked down at a secluded beach below. I saw a lot of tourists there, lying on the beach or bathing in the sea and all stark naked, men and women together. I ran back and told my uncle about it. He seemed very surprised and I expected him to go and tell the gendarme to have them all arrested. But, instead, he opened a cupboard, took out a large pair of binoculars and after asking me to describe to him exactly where the place was, he told me to stay in the village and not tell anyone else about it. He then set off and didn’t come back until several hours later, looking rather tired but very pleased with himself.”

There were loud jeers and laughter at the end of Dimitri’s narrative and Mr. Sfaliaras had to call the class to order by threatening dire punishment.

“The subject of nudism is closed,” he said sternly. “I will go on with my lecture and I want no more interruptions from anyone.

“Now, as I was saying, tourists do not come to Greece only to enjoy the sun and the sea but also to gaze with awe and respect on the monuments of our ancient civilization and works of art that have remained unsurpassed to this day.”

He was rather pleased with that turn of phrase and stole a glance at the class over his spectacles to see what effect it had had. Mikroulis’ hand was up again. Mr. Sfaliaras shuddered. “I said no more interruptions.”

“Just one question, sir, please,” Mikroulis begged.

“All right, what is it?”

“Sir, are there any monuments of ancient civilisation in Crete?”

“Certainly,” the teacher replied, “the remains of the Minoan civilization which is the most ancient of all,” he said.

“Sir, I read in the newspaper about two young tourists from England who were not looking at our monuments with awe and respect but were making love in the street in Neapolis in broad daylight and were sentenced to one month in prison.”

The class broke out in cheers. After he had restored order again, Mr. Sfaliaras said:

“Well, that only goes to prove that such indecencies are not tolerated in our country and that the culprits must have bitterly regretted their erotic incontinence.”

“I don’t think so, sir,” Mikroulis said, “I heard from a friend of my father’s who is a journalist that they were each paid two hundred and fifty pounds for their story by a British Sunday newspaper when they got out of jail.

“A disgraceful affair,” the teacher snorted. “Well, I’m afraid that does it, boys,” he said with finality. “You obviously know much more about tourist activities in this country than I do, so I see no point, in going on with my lecture. We shall do History instead, and since we seem to be dealing so much with bottoms today, you will kindly bring out your history books and open them at page ninety-eight where you will find the chapter on Theodore Kolokotronis.”

Later that day, Mr. Sfaliaras wrote a long report to the Minister of Education giving the reasons why he did not think it was a good idea to devote an hour a week to teaching his charges how to behave with tourists. He concluded his report with the following sentence:

“In view of the incidents mentioned above, which were described to me in all innocence by the young children in my class, 1 respectfully submit that in future, proper measures should be taken by the authorities concerned to make sure that if foreign tourists in our country engage in photography, they should be constrained to doing it with cameras alone.”