St. Paul may have visited, but he never wrote. Thus, the island of Lesvos, or Mytilini, is possibly best known to the West as the place where the Lesbians come from — a scurrilous notion based on the poetry of Sappho, who wrote enthusiastic love poems to all her friends, 2500 years ago. The lady appeared to display good taste, since they say that the women of this island, especially those of Dafia village, have always been admired for exceptional beauty. One hesitates to even speculate on St. Paul’s “Epistle to the Lesbians”, unknown to posterity. Maybe he funked it.

This isn’t a blue-and-white postcard island: it’s red and brown and green and silver — the third largest Greek island, after Crete and Euboea. It takes 15 hours to get there by sea from Athens. It’s shaped like nothing so much as a jigsaw piece, with two large and one small peninsulas separated by two bays.

The landscape varies from orchard to forest to the ‘Sahara’ of its western stretch. The coastline is uneven, so beaches abound. It’s been discovered, but not by so very many. Local archaeological sites are disappointing — but the heartbeat of this island is more ancient than that of any site. Rituals persist beyond memory.

When you have seen the tiny churches and the grand ones, built in gratitude or devotion, the ancient temple, even in ruins, begins to take on meaning. That fallen column and lump of carved rock are all that is left of an older act of dedication. The broken wall may well have been painted with images of legends. Certainly, the ancient temples have disgorged their share of tamata — the votive offerings of statues, jewellery or modelled parts of the body — seen draped on the holy icons in every church.

Accomodation may be found at hotels, pensions, ‘rooms’ — which may mean anything from a cell to a self-catering suite — and apartments. These categories, like the official A, B, C, D, and E, are meaningless to the consumer, since a D class room may be much more comfortable than an A class hotel, although the decor tends toward the monastic everywhere.

As a border island, it is garrisoned, and there are a few stations in the hills where photos are forbidden.

It was only one grandfather ago, in 1912, that the island became part of the Greek republic. A big island with good harbors located close to the coast of the large land mass of Asia Minor naturally functioned as a depot for cross-Mediterranean trade.

Equally naturally, it was a tempting morsel. In ancient times the relationship of Lesvos with Troy was close, and Homer says that Achilles and Odysseus both landed forces on the island. Mithymna (Molyvos) and Mytilini both sought to dominate, and later, though Mytilini won, Molyvos frequently showed signs of rebellion against the capital. The dictator Pittacus (589 – 579 B.C.) finally brought peace and prosperity: a large merchant fleet carrying goods back and forth from Egypt made possible such luxuries as education and culture — and an astonishing amount of women’s liberation. Aesop of the fables came from Lesvos.

Then the Persians and the Athenians tussled over the island — the two towns taking different sides — with the dire result that the island was condemned to the sword by Athens. Shortly afterward the Athenians relented, and there was a breakneck chase of the first galley in order to cancel the execution command: the marines arrived in the nick of time.

Until the Byzantine empire, the island was occupied by Persia, Alexander’s troops, the Ptolemies and the Romans. Julius Caesar was blooded as a warrior in the conquest of Mytilini.

The Byzantines used the island as a place of exile, and incursions by the Turks compelled the population to retreat into the hills. From then on Lesvos was bounced from Byzantine to Seljuk to Venetian: then to the Greeks in 1247. But not for long. Catalan soldiers of fortune grabbed it, only to lose the island to Genoese allies of the Byzantine Palaeologos restoration.

Back to peace and prosperity until the Turks came again in 1462. However, the prosperity continued, along with special status. During the Greek revolution of 1821, sympathizers suffered massacre and torture. Finally, just before World War I, the island was joined to Greece. There was a German occupation force during World War II. The island generally tends to swing left politically.

The airport and the capital port are together on the east coast, and roads radiate north, south and west. Although there is no air pollution from vehicles — since in seven hours of driving you may see only one other car — you may be squishily reminded that the road is basically for the animals, who have the right to wander as they will. Running over goats, donkeys, dogs, chickens and ladies is a distinct possibility. The loads of grass and leaves on the donkeys are fodder for the goats.

It is possible to identify saints even in these times as, after death, their bodies do not decay, and smell of perfume. In the Cathedral of Ayios Athanasios in Mytiline is the body of the local St. Theodore, who converted to Christianity in 1795 and was martyred by the Turks. Plague came. He appeared in a dream to the sexton, saying his body must be disinterred in order to stop the deaths. On his third appearance, the deed was done. The Pasha agreed, as many Turks were dying as well, and the miracle occurred: the plague ceased. St. Theodore’s head was accidentally removed by the workmen and is separately encased, while his hands are visible through glass on the coffin, which rests in a sarcophagus in the church. There are 28 more of these local saints depicted in the vestibule.

And, of course, when visiting churches and monasteries, bare shoulders and legs are not admitted: bring a wrap on island tours. In fact, even trousers on women may invoke frowns, though skirts on men do not!

The Archaeological Museum is rarely functioning: the Ministry of the Aegean took over the neoclassical mansion they were using, leaving only one room to house the mosaics from the ‘House of Menander’ which depict Orpheus charming animals, and figures from comedy. The mosaics are in fine shape and very handsome, but that’s the show, apart from what’s in the garden.

They hope to find a home some day. The museum is around on the north harbor, between the ‘Statue of Liberty’ about which little need be said, and the town beach. Underwater ruins can be seen here.

There is an ancient theatre which is said to have impressed the Roman general Pompey and which can be reached up a dirt road to the north of town. What’s left of it is a grass bank and some tumbled stones, and all that remains of the theatre is the stage.

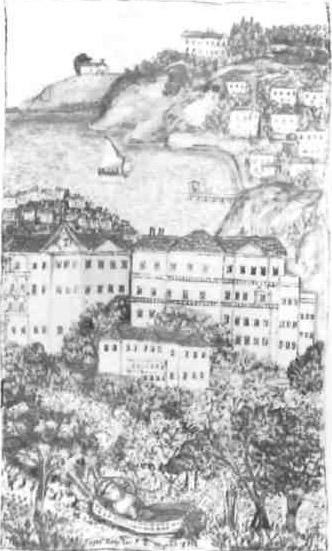

But there is a most wonderful, huge, complete Byzantine castle which was renovated by Genoese in 1373. It may well be the largest castle of the Mediterranean. ‘Dungeons and Dragons’ players, this is what you have been dreaming about: it covers a whole hill, bastioned into the sea, has wall after wall after tower still standing, not to mention dungeons, crypts — and possibly dragons — within the walls. There’s even a Turkish theological school inside. The site must be even older, since Hellenistic remains were found inside the upper bailey, and restored tholos (domed) houses outside. (Open during daylight hours except Monday).

The church of Ayios Therapon has a Byzantine collection and there’s a rarely-open folk museum on the south harbor, just by the bus station. Buses run on weekdays until 5 and sometimes 6 p.m. — often returning only at 7:00 a.m. from the villages.

There are two remarkable museums in Varia, three kilometres south of town. In an olive grove are a couple of elegant marble buildings. One is the astonishing “Teriade” Museum, and if you have any interest at all in 20th century art, this is a must. It was founded by the Greek, Eleftheriades, who went to Paris to study law. He became interested in contemporary painting, and published collections of the prints of Matisse, Picasso, Leger, Rouault, Chagall, and other modern masters, which are displayed here. There are also some fine books of hours and illuminated manuscripts. An exhibition of excellent modern Greek painters includes a wonderful portrait of Theofilos as Alexander wearing armor over his pyjamas, with a potato-like palette and a headless spear and looking utterly demented.

Teriade is also responsible for the Theofilos Collection in the other house, which is dedicated to the works of the wandering painter of the early part of this century. Theofilos bartered paintings for food and lodging, and he has left a detailed record of costumes, daily activities, dancing, eating and patriotic visions. He presents a loving record of an age gone by: he had an eye for faces, and was an acute observer, if undeniably weak on anatomy. Though his figures are strangely out of drawing – the heads too big and too detailed – somehow you really get involved in the pictures. They accumulate great significance when seen en masse.

In and around Mytilini you often see the peculiar mansions built in the 19th century by rich merchants. They are usually symmetrical, with tall towers on either side, and very narrow, often with empty niches where statuary ought to be. Many have been demolished, though lately there is a movement afoot to rescue and restore them.

Outside of town on the road to Molyvos is a forested recreation area with picnic grounds, sports and water, close by Thermes of the famous hot springs. Remains of ancient walls can be seen here.

There is plenty of mountain water to keep the island green, but irrigation is imperfect, so the coastal areas get dry in summer. The villages along this main road but beware of potholes – are pretty, some old Turkish. You pass an occasional kentro a place of food and entertainment – and some attractive beaches with clean water.

The village of Mandamados, low stone houses with tile roofs ranged up the hillside, is known for the unusual Church of the Archangel Michael, the Taxiarchis. In the courtyard is a whitewashed tree, with chains hanging from its branches. Against the walls are the marks of fires. A few weeks after Easter every year, a bull is hung from those chains, and ceremonially slaughtered. The meat is cooked in giant cauldrons near the walls and shared with the congregation. Rooms are rented in this courtyard to pilgrims who have come a long way for the ritual.

Inside the church is an icon so numinous that it summons a constant line of visitors, apart from the formal pilgrimage. Crowned and winged with silver-gilt, a sculptured umber face with round, anguished eyes and vermilion lips stares from behind a mound of flowers. The amateurish modeling is irrelevant considering the blazing intensity of the angel’s gaze. The story tells of the bloody massacre of all the brothers of the monastery. When the Saracens had galloped away, the lone survivor scraped up the blood and the soil and made this head of the Archangel, who comes for the souls of the dying.

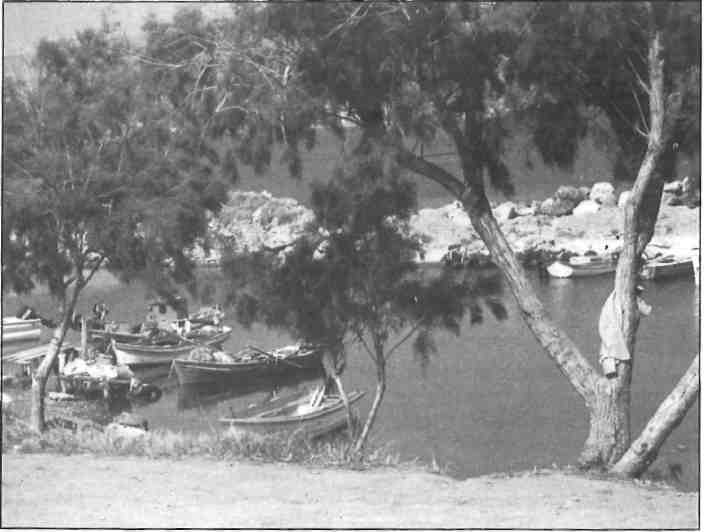

At the northeast corner of Lesvos is Skala Sikamias, a tiny harbor of fish tavernas, a few rooms and shops, a lovely little beach place for a holiday. The tourist shop owner makes tapestries in the winter, small works of art in wools depicting village streets, boats, courtyards.

Across the peninsula is Molyvos or Methymna, along a dirt road. For a while there is only scrubby hillside, then a pleasant taverna (with great bread) at Vafios, then the dark green trees and red tile roofs of Molyvos, ancient rival of Mytilini.

The well-preserved small castle here is roomy enough inside for picnics and offers a splendid view of the island. This was one of the last places to fall to the Turks. In summer it’s the site of a theatre festival.

The town is a delectable, perfect, fairy-tale place – narrow cobblestone streets arched with vines and flower-aped balconies, a tiny agora with minute shops deservedly full of tourists by the end of May. The authorities have decreed that no modern buildings shall be erected in this town, though there are hotels and rooms to let, tavernas, a post office and even a bank. Some restaurants are perched dizzily on the cliff edge.

Two kilometres outside of town is the Naruna Yoga Retreat Centre. You can write to Mr and Mrs Kassipides, Mithymna 811 08, for information about their summer program.

A sort of scaled-down version of Molyvos is Petra. It too is charming and picturesque. The Church of the Madonna of the Rocks – actually, she is called the Panayia GlykotHoussa, Madonna of the Sweet Kiss – is reached by climbing 114 easy steps. Built between 1780 and 1840, it has a baroque iconostasis of carved and painted curlicues and flowers. The icon is much loved – i.e. kissed – and covered with tamata. Petra is host to the women’s collective which rents rooms and runs a very popular restaurant. There is a fine sand beach, and one of the best beaches on the island is found in the tiny village of Anaxos nearby to the southwest.

Along the main road westward from Mytilini is a hidden ruin of a temple to Aphrodite, rarely open: there are salt flats called Aliki – not to be confused with Aliki, who went to Wonderland – on the edge of Kaloni Bayie below the road. The towns are full of tiny, twittering swallows, which hunt wildly at dawn and dusk. All the villages are growing here; building is happening all over — Arisvi, Kalloni, known for the breeding of horses – mountain and dale, orchards and sheep farms. But Dafia of the beautiful women is building a new area that looks like barracks.

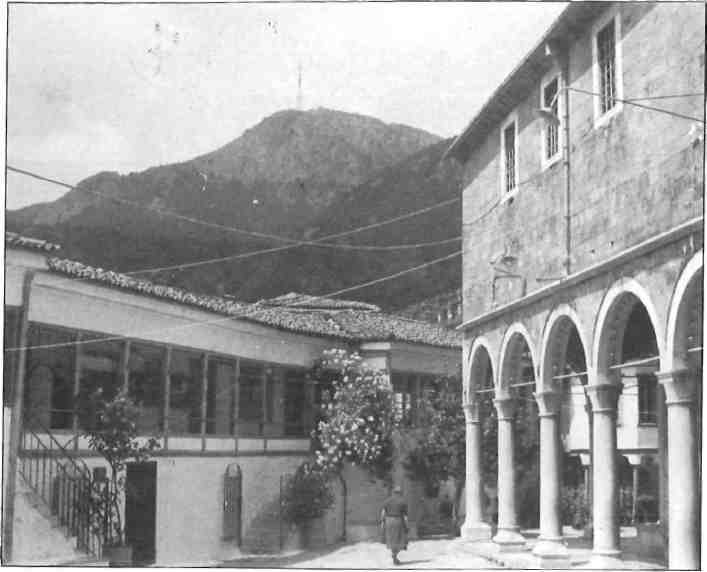

The monastery of Limenos is tended by a collector. Prior Nicodemos Pavlopoulos has proudly increased the library from 2500 volumes to 15,000 works on theology, science, history, the arts and philosophy. He has also painted all the ceilings with red, green and white patterns. Women aren’t allowed inside the ancient church, but there is a museum of coins and relics attached to the monastery (admission 100 dr.)

There is work from the hand of the painter and calligrapher Ayios Ignatios, and his chair has been here since 1500. A case of icons of the Madonna and Child by different hands over the centuries conveys the idea that the same picture has continued to clone – same pose, costume, expressions, with a few minor variations of pose. A room of manuscripts is entirely fascinating: illuminations dating back to the ninth century, firmans – Ottoman permits, very fancy – and manuscripts of Byzantine music, one of which is mysteriously notated in concentric circles. There’s also a display of folk arts – household and farm implements. The wooden things with several round bowls carved into them are not eating dishes but bread-raising trays.

There’s an incredible vista of folded hills and valleys on the road to Filia, which is lined with what one can only regard as ‘iconoliths’. Those rocks in the backgrounds of icons are not an invention, after all: they are faithful renderings of the repeated formations found in nature in these parts.

Little old Perivoli Monastery is guarded by a little old lady. It has lovely but faded frescoes. You need a flashlight to see them.

The road from Antissa leads into the so-called ‘Sahara’: bleak, bare hilltops, covered only with lichen. The pine forests are only a memory now. A few sheep nibbling- at what? – are barely distinguishable from the rocks. Scrubby silvery plants lead to salt flats and a beautiful sandy beach.

At Sign there is a hotel and good fishing. It’s a bit shadeless; everything is new, whitewashed stucco. There’s a castle, rather truncated as to top. A little cafe bar called the Galazio Kama offers fresh squid, and a signpost points eight kilometres to the Petrified Forest. The road is enough to make strong men quail: it begins with pointed rocks sticking out of it. Far more relaxing, if not cheaper, is the little boat which runs back and forth till late afternoon for a fee that varies according to the number of passengers.

Once off the little boat, follow the clear path to the opposite side of the peninsula to see a few stone logs lying in the water. Don’t wear open shoes here. Climb down to the shore if you want to inspect the glittery mica embedded in the bark. But there really isn’t much to see: one standing tree lies over the hill, much easier to see from the water.

Back to the road, through the desert: now the hills are crowned by castles, but they are natural formations. Eressos is a pretty town, with terraces, orchards and old stone houses; old geezers with hankies on their heads riding donkeys and young geezers with nothing on their heads riding motorcycles down to the shore, Skala Eressos. There are tourist shops and plenty of rooms to rent, and a one-room museum next to the site of a basilica, of which fragments of mosaic and a few broken columns remain. The museum contains figures, inscriptions and pottery, all found as people were building houses near here. The beach is very comfortable and nice, lined with attractive tavernas. Topless bathing is allowed.

There are an old castle and a classical site at ancient Antissa. Rock along a rocky road, between rock walls and plain rocks, bearing right. (A wrong turn brings you to a charming village called Skala Campo.) At the end of a weary ride are a couple of tumbled walls (by an isolated, unfriendly kafeneion) only of interest to a manic archaeologist. It’s a relief to get back to friendly Skalahori, a beautiful town of cypresses and silver olive trees, where there are rooms to let. The road leads back through Kalloni to Mytilini.

The southern peninsula is dominated by Mount Olympos, a white formation that thrusts high above the green hills beneath. The central road leading to Ayiassos is badly marked: head for Olympos, bearing left. The road is woodsy, with brooks, and the olive trees are sometimes individually terraced.

Ayiassos is not yet spoiled, although there are tourist shops among the old houses with Turkish enclosed balconies, and twisting cobbled lanes. The grand Church of the Panayia features not only gold covered icons, but even a Madonna and Child in encaustic (wax and mastic) supposedly painted by St. Luke himself, hidden behind the altar. Even the copy, which is displayed, is shimmering with gold and inspires reverence. The church also rents rooms in the enclosure, and has a fine ecclesiastical museum which contains a staggering amount of treasure that has been donated as tamata, as well as costumes, embroidery and pottery. On the Feast of the Assumption of the Virgin, 15 August, people make the pilgrimage from all over the island on foot. There’s a small folk art museum too.

The road south leads past the Sanatorium, which is, like Mann’s Magic Mountain, located in the purest air to be found. Here you can drive for miles through the chestnut trees, wild pine woods, sycamores and fruit trees. Birdwatchers, this is the top of the world. You can see all the way to Asia on a clear day. The little white boxes along the road are beehives.

On the dirt road west from Ayiassos to Polichnitou, recreation and picnic grounds beckon from among tall trees just by the turn to Ambeliko.

Polichnitou is a famous hot spring spa: Skala Polichnitou is a summer place with lovely little cottages to let, rooms and flats, and the still-but-just-barely peaceful Nifida Beach nearby is fast under development. The shore is both pebble – which changes to sand about 20 feet in – and sand, and there is a tiny harbor for tiny boats.

South of Polichnitos is a sort of hot Yorkshire – rolling hills with low scrub -but the road soon climbs back to the piney woods. Ayios Fokas has a good long sandy beach, not much developed, with goats in the bushes. There is an uninteresting Temple of Dionysos site, near the church which boasts a real honest-to-god Formica iconostasis. But the little harbor and fish tavernas nearby might be worth the drive.

South of Ayiassos to Plomari, the dirt road passes though the village of Megalohori, which is not at all rnegalo (big). Through wilderness, unpaved, un-frequented – and yet, a sign of life now and again. A souvlaki bar? Here? But we have reached paving! We have reached tavernas! We have reached civilization and Interamerican signs!

Coming down the mountain with ears ringing, there is a beautiful view of the bay and Ayios Isidoros, Plomari’s beach. This town is in the process of being created though, at sundown, little groups of women embroider on the front steps that line the cobbled streets. Houses are painted in shades of beige and red. Just outside of town is the Barbayiannis ouzo factory: this town is the ouzo center of the world.

On the way back to Mytilini and skirting the lovely Bay of Yeras, there are elegant beaches against a backdrop of forested hills, olive groves and cypresses – but nobody can swim here because of the pollution from factories at Perama.

At dusk you may be somewhat impeded by the efforts of sheep to cross the road to their stables.

There is so much variety – topless beaches and yoga and mind-blowing icons and flowers and boats and castles and animals and organic gardening and hot springs and discos – and so much island that a car is necessary for at least some days.

Too many of the islands are being destroyed by fires. One can hope that this one will continue to be lucky and keep those cool, scented pine forests intact.