About 1500-1600 BC the volcano of Thera, or Santorini, erupted. It was probably the most calamitious event of the Late Bronze Age, the effects of which are still being examined by scholars. The debate continued last month with a meeting of archaeologists and geologists on Santorini at the III International Congress on Thera and the Aegean World. At this meeting, experts who have devoted years of study to the eruption and its effects asked again the still unresolved questions: When did the eruption occur? What were the cultural effects in the Aegean, and throughout the eastern Mediterranean? How long did the eruption last? What was left behind in the form of volcanic and cultural evidence to provide answers for these questions? How did the Minoans who lived on the island know when to leave, since the excavations at Akrotiri indicate everyone fled with food and valuables?

Under the aegis of the Greek Archaeological Society, the Greek Geological Society, the Greek Institute of Geology and Mineral Exploration, and the University of Athens, over 160 scientists from around the world formed the inaugural group which convened in the new convention facility in Fira, the island’s capital. From 3 through 9 September these scientists debated and argued; they presented their research and opinions, and fanned the controversy that has lasted for decades, especially since Spyros Marinatos’ claim, in 1939, that the island, prior to blowing its top, may have been the fabled Atlantis.

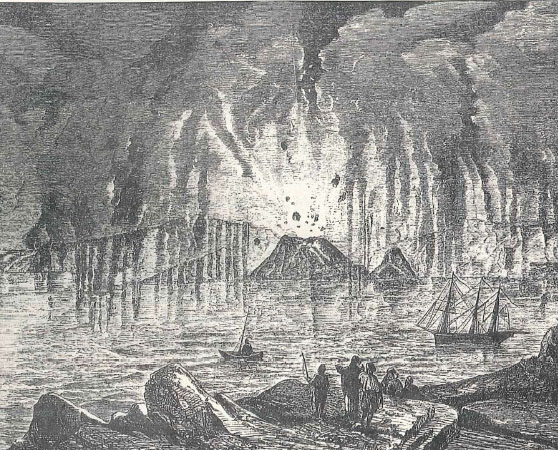

There is little doubt that the eruption was one of the largest in recorded history, larger than that of Krakatoa as well as the more recent eruption of Mt. St. Helens. The cultural impact of such a major natural event must have been phenomenal as well. Volcanic dust, earthquakes and tidal waves certainly contributed to Late Bronze Age chaos. Geologists described the volcanic dust on Thera, where it forms a white mantle over older volcanic deposits, and contributes to the spectacular natural beauty of the island cliffs. Over 100 metres thick on the island, this dust was spread far out to sea by winds, settling onto the deep ocean floor as a distinct layer. New finds of dust in the Nile delta and in central Turkey dramatically indicate just how far this ejecta spread.

Ash has now been found at numerous archaeological sites – Rhodes, Kos, Crete and on Pseira, an islet in Mirabella Bay in Crete – but the most famous site is Akrotiri on Thera. At many of these sites, earthquake damage either preceded the eruption or accompanied the volcanic desolation. Archaeologists have noted changes in Late Bronze Age Minoan culture that must be an indication of the eruption’s aftermath – new pottery styles, changed techniques in art, an overall different assortment of cultural debris. On these points discussion at the congress was more concerned with finer interpretations of the differences with respect to pre and post-eruption cultures. The larger premise – that the eruption was the mechanism for change – was agreed upon without considerable debate.

Not so with the discussion of just when the eruption occurred in the Late Bronze Age. Here debate flourished, and will continue to do so. Did the eruption occur at about 1500 BC or at about 1620 BC? How to tell remains a problem. Dating relies upon radiocarbon techniques, potsherds, tree rings, even distinctive ice layers in Greenland. Absolute dating, to identify a specific year, comes from carbon 14: living tissue stops absorbing C14 when it dies and C14 then slowly decreases so that half the amount is lost after 5730 years. But C14 dates seem indicative of both a younger (1500 BC) and an older (1600 BC) chronology, depending upon the biases held and interpretations accepted, as well as how corrections of C14 dates are made. Corrections must take into account what material was dated. For example, a tree used for building might be a hundred years older than the destruction date, so a C14 date on this wood is not precise.

Seeds buried beneath ash at Akrotiri should provide quite precise dating, assuming they were from the harvest immediately preceding the eruption. Yet groundwater circulating through the ash into the buried seeds could cause contamination and reset the C14 clock. So could many other effects, the most significant being changes in C14 input to the earth’s surface with the passage of time, especially since World War II with atomic bomb testing. Advanced techniques in C14 methods promise help, and there was support from new dates at the congress supporting the older chronology. Potsherd chronologies only indicate changes through time; they are fixed to calendar years by radiometric dates (e g C14) obtained either at that particular site or at other sites through extrapolation of similiarities in sherds.

Tree rings from Ireland and the southeastern US seem to point to an older date for the eruption. A cold summer in about 1645 BC is suggested from very narrow growth rings, perhaps an indication of much dust in the atmosphere. If it was volcanic dust, then it could have been enriched in sulphur, thereby producing acid rain. Thin layers of acid ice deep in the Greenland ice cap suggest just this, and also point to a circa 1650 BC eruption.

Not so simple though. New research around the globe points to at least three other major eruptions just then: in Italy (an older Vesuvius eruption), in Indonesia and, in Oregon, at Mt. St. Helens again. How high the Late Bronze Age Thera ash sulphur content was was a point much debated, and it seems that there is no reason to assume a high concentration. Thus the issue remains unresolved. A tongue-in-cheek vote showed as many scientists prefering the older chronology as the younger.

Newly recovered portions of the beautiful marine fresco have been assembled and now as many as five towns seem to be depicted in this famous scene. Interpretations of this single fresco vary: some see indications of Late Bronze Age boat sheds; others, a study of the ecology of the Minoan environment; still others, a portrait of the pre-emption geography of Thera. It appears that several artists may have had a hand in painting the fresco of the lilies and swallows. Additional papers discussed Late Bronze Age seaport facilities, the role of religion in Theran life, estimates of population size on the pre-eruption island and clays used in making pottery. Comparisons were made with other major historic eruptions of the past two centuries with the idea of reaching a better understanding of, for instance, how long the Minoan eruption continued, or how violent it was. While it is only proxy evidence, there is little else to go on except for this remaining piece of cultural and geological debris.

And so the debate continues: this is the fun of science. When two groups of scientists with similiar questions and interests, studying the same phenomenon, can be brought together to compare notes, the consequences are dramatic. The book detailing this discussion and research will be equally compelling; publication is scheduled for early 1990. But this unique meeting of representatives from the natural sciences – archaeologists, mainly – and physical sciences (volcanologists, marine geologists, geophysicists, geochemists) did agree on some very interesting major points that will res-tructure thinking about the Thera eruption and its effects on the southern Aegean.

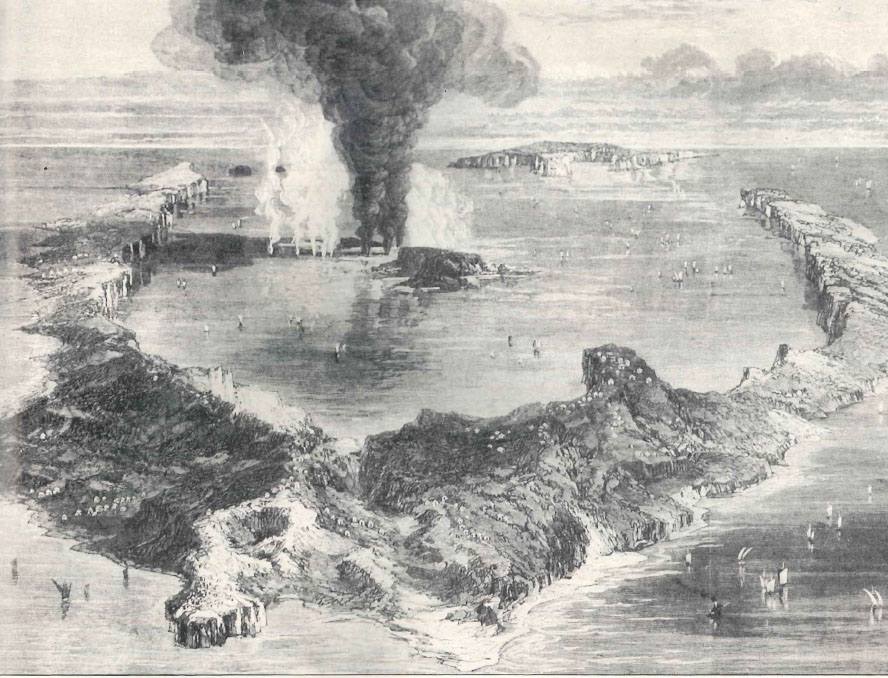

First, the eruption marks the transition from Late Minoan 1A to LM IB on the Crete and Cyclades archaeological time scale. Second, pre-eruption Thera was not a lofty, high mountain as is so often fancifully depicted, but ancient Minoan Santorini had a large central depression much as it does today. There is agreement among geologists that the southern part of this depression was a large embayment open to the sea via a channel between the Akrotiri Peninsula and the island of Aspronisi. How much of the northern embayment was flooded or was low-lying dry land remains under discussion by geologists. Third, there was agreement that the entire eruption took place over the course of only a few days, if not hours. Thus disappears the idea of a caesura during the eruption.

Fourth, the Minoans were warned of the impending disaster by repeated small earthquakes and by a small eruption of ash preceding the big blast. These earthquakes did not cause extensive damage; rather widespread destruction throughout much of the southern Aegean was the result of an enormous earthquake unrelated to any eruption that occurred generations before the Late Bronze Age eruption. The series of small ash eruptions occurred hours or days before the major eruption and certainly should have provided the final scare.

Finally, scientists pleaded for the opening of the newly-built museum in Fira, with temperature and humidity controls to assure the preservation of the frescoes. Another recommendation stated that excavations at Akrotiri, under Dr Christos Doumas, be renewed; that financial support from public and private sources be dedicated to exhuming the other wonders of the Late Bronze Age that must certainly be buried beneath the volcanic ash.

The new conference hall perched on the cliff edge in Fira was a beautiful setting for the meeting, a reconstructed kokkina spilia (red cave) built at the turn of the century and destroyed by the 1956 earthquake. With skilled contributions from architect Dimitris Koutsoudakis and contractor Panayiotis Roussos, coupled with magnificent designs from Minoan frescoes added to the ceiling by Andreas and Ionia Abaelopoulos, as well as to an enormous fronting curtain by Doha Nomikos, combined with the vision of Petros Nomikos, this reconstruction has produced one of the finest meeting facilities in the world. A set of volumes will be published to preserve the findings of this meeting. A two-volume set from the II Thera Conference is also available. Inquiries and orders should be directed to the Secretariat of the Third Conference, Thera and the Aegean World, 105/9 Bishopsgate, London EC2M3UQ.

Dr Floyd McCoy, a vulcanologist and marine geologist affiliated with Columbia University, has been researching the vulcanology of Santorini since 1967.