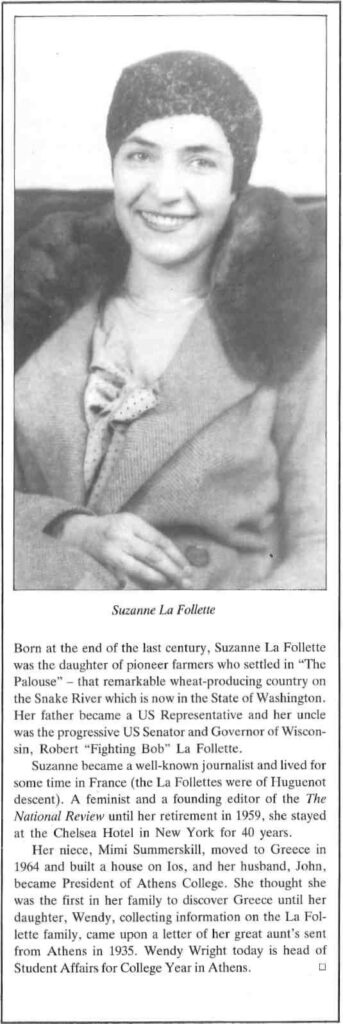

Dearest family,

Attica would not surprise you. Just imagine the Yakima Valley opening out on the sea, and there you have it. Of course there’s a lot of difference geologically. This country is all marble and calcareous stone, and the buttes that jut up out of the plains are solid rock with almost no top-soil – in some places none at all. The Parthenon stands on bare rock which is a mixture of pale blue and pink, and the places on which stood the bases of statues and temples were levelled off by cutting into the living rock. The troughs for carrying off rain water were also hollowed out of the stone.

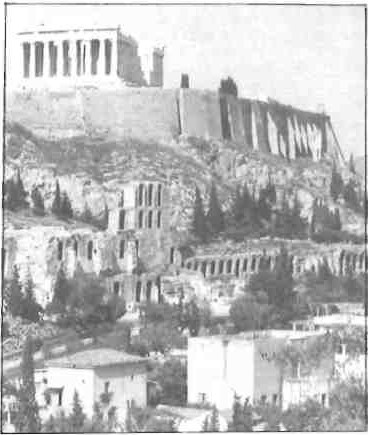

The wind blows a constant gale. On the Acropolis it’s terrifying. They tell me it’s not always as bad as it has been this past week; but the state of the vegetation shows that there must be more windy days than not; for it is warped and stunted. And the dust blows with the wind and fills the air on the windiest days. When the air isn’t full of dust it is marvelously clear and pure, very much like that of the Palouse country; and invigorating like that. They say Athens wasn’t quite so dry in ancient times, but almost. Like the Palouse country it has a rainy season and a dry season, and in November one sees it at the end of the dry season, when it is at its very driest, just like the Palouse. The rivers are trickles, the earth is parched and dusty and the vegetation looks rather discouraged. There is a large and quite decorative bed of cactus thriving under the west front of the Acropolis.

The trip from Brindisi was interesting. The boat was so tiny that I promptly paid eight dollars more to move into first class, for second was away at the back and I knew if the sea were the least bit rough it would be terrible back there. There were only two other first-class passengers; the former Italian Consul-General at Boston and his wife, on their way to their new post at Istanbul. Very nice people indeed – she much younger than he and very beautiful, and he a most cultivated and pleasant person.

Toward evening of the day we left Brindisi we passed the island of Corfu off to the east, only near enough to see its outline against the sky. The next morning when I awoke about seven o’clock we were in the Gulf of Corinth, with the bare mountains of Greece rising on either side. Now and then one saw a wooded slope, but most of them were quite bare, and really wonderful in color, for they were pale grey and tan – sometimes a tan so pale it was almost white – and many of them were mottled with pink and purple and ochre. They weren’t monotonous, as bare hills so easily can be, for their contours and their colors were beautiful and varied. And the colors weren’t patches of vegetation; they were patches of colored stone.

These Greek hills take the light in a very special way, because, being marble and calcareous stone, they are translucent. It – I mean the difference between these and other hills – is like the difference between a marble statue and one of granite; the one is much more luminous than the other.

We arrived at the Corinth canal just before dark. It is just a great slash in the earth; I should say about 300 feet deep at its deepest part. And because it isn’t walled up on either side, it’s forever caving in, the captain told us. We saw several places where there appeared to have been slides. The sides are pale tan and the earth looked to be about the consistency of chalk. It’s very narrow; we were towed by a tug which had to follow the exact middle of the canal, for the clearance on either side wasn’t more than three or four feet.

We emerged on the other side just in time to get a look at the islands of Aegina and Salamis before nightfall – and of course at the mountains of Megara. When we finally made the dock at the Piraeus it was about ten o’clock – and we were supposed to arrive at two! But the regular boats of the line had been diverted to the use of troops being sent to Abyssinia, and this was a little slow boat that could make only 12 knots an hour.

To make matters gloomier, we landed at a freight dock, so crowded with cases of goods, bales of wire, and God knows what else that only with difficulty could one pick one’s way out of the place. I had no trouble, for I put myself in the hands of the Thomas Cook representative who met the boat; and he saw me through the customs and brought me to my hotel in Athens. The next morning I moved to this hotel [the Grande Bretagne] and was disgusted because I hadn’t come here at once, for it had a representative at the boat, and I might have saved the money I paid Cook’s or part of it. But I hadn’t come here because I thought it was too expensive. One has to stay in the best hotel here I find, because the others are pretty dirty. This one is first class, even according to American standards. In America it would be prohibitive; here I get my room, breakfast and dinner for little more than three dollars a day. Moreover, the place is heated, which is unusual. And it’s real Palouse country November weather. Possibly not quite so cold, but almost.

Of course I went up to the Acropolis the first day I was here. It was so windy up there that I had difficulty getting a chance to look at the place, so busily engaged was I in hanging onto my hat and clothes. I took a brief look at the Parthenon and the Erechtheion and ducked into the museum where the air, if cold, was still. It is a wonderful museum of the archaic period. They have the archaic sculptures from the first Parthenon, and the Ionic votive statues, which are simply magnificent. They have a remarkable amount of color left on them. Some pieces from the frieze of the Parthenon are there too, and the plaster casts of the parts which are in London.

My second visit to the Acropolis was more successful. It wasn’t quite so windy and the sun was shining. The temples were beautiful. The marble had taken on a lovely warm tone with age and in the sunshine against a blue sky it is beautiful beyond description. The Erechtheion is a little gem of a temple with its decorative detail in a rather good state of preservation; so delicately carved that it is utterly delightful. And the famous Caryatids are most beautiful. One of them of course is plaster, the original being in the British Museum along with Lord Elgin’s other loot from the Acropolis.

It’s curious how the sculptures of the Parthenon carry, even without being thrown into relief as they once were by color on the background. The Acropolis stands very high above the street, and from below one can see the metopes that are left on the west front quite clearly.

It is rather sad to visit a dead city, especially one which literature has made as familiar and as dear as Athens. One is so often disappointed in the places whose names have meant enchantment for so long. The famous IIissos is now a dry bed with a little more water in it than there is in the Wawawai Creek. It is said to have dried up considerably since antiquity. And it stinks! The people alongside use it freely as a sewer. They are now demanding to have it piped, for although one thinks it is all right to pour his own filth into it, one resents the filth of his neighbors. While I was exploring what the guidebook says was the famous fountain of Kalirrhoc, an old gal came out of one of the houses near by with a bucket of dirty water and flung it into the stream so near me that I almost got splashed. With all due respect to all the guide-books and archaeologists, I don’t believe that a waterfall in the IIissos is the fountain of Kalirrhhoe. I never before heard of a waterfall being called a spring. A German archaeologist, excavating the east foot of the Acropolis, found a dried -up spring, which he with apparent good reason, called the fountain of Kalirrhoe, and I’m inclined to think he was right.

That same eastern slope has quite a lot of the old city exposed to the light by the Germans. I wandered through it this morning. It’s perilous going, for it’s full of wells and cisterns, which the government should rail off and doesn’t. If one stepped into them one could break a leg or drown in filthy water, depending on which one happened to strike. The remains of the houses show that they were quite small. There were traces of red and green decorative bands on the walls of one, and several had pavements of a curious crude mosaic made of long pebbles set in what I took to be cement. One sees this pebble mosaic a lot in modern Italy, but not indoors. The streets were very narrow and crooked. Wells and cisterns, as I intimated, are everywhere in striking profusion.

No wonder Athens had a pestilence during the Peloponnesian War. The wonder is that it didn’t have one at least once a year. Fancy drinking water from a well in the midst of a congested city! In the Agora, they tell me, the American School has found wells and cesspools nestling cosily side by side. Ugh!

I’m to visit the Agora early in the week with a young epigraphist from the American School to whom I’ve been introduced by the representative of the New York Times. One can get in only if one is taken there by someone from the school. It isn’t open to the public. I looked down into it the other day from the temple of Hephaistos, usually called the Theseion. One could get nothing out of the digging unless one went there with an archaeologist, for it is just a lot of foundations with here and there a mosaic pavement intact. The Theseion, which is the best-preserved temple in Athens and I think perhaps the best in Greece, is most deceptive. Seen from the Acropolis it looks enormous. And when one gets to it it looks quite small, not more than quarter the size of the Parthenon. And rather cold.

This morning I visited the Pnyx. Why the Athenians chose to build the place for their assembly instead of letting the people sit on the hillside and building the tribune at the bottom I wish I knew. It’s the damnedest arrangement I ever saw… In ancient times, the Pnyx had somewhat the shape of a shell, with the outer edge as high as the tribune. And in this vast shell-shaped space the citizens of Athens sat on the ground and listened while Aristides, Themistocles, Pericles, each in his time, told them what was what. I mounted the tribune and harangued the crowd, but the wind carried my words to no ears, and they weren’t Greek words anyway. It seemed rather futile, so I departed, and as I left the guard gave me a sprig of sage from his tiny garden and I gave him two drachma, which was one drachma more than the Athenian citizen was paid for attending the public assembly. But I fear it was less than that, for the drachma is worth a little less than one cent.

This afternoon I visited the cemetery which was outside the walls of the ancient town… The tombs were very grand; in fact, they became so magnificent that a law had to be passed forbidding expensive monuments. Most of the monuments from the cemetery are in the National Museum, in the city, but a few are still in place. The finest I saw wasn’t all there; only, on the top a life-sized bull in Pentelic marble, very life-like and full of the old Nick…

In the museum are hundreds of beautiful vases found in these tombs,and many terra cotta figurines, and some jewelry. I wonder if my Greek necklace came from here. I shall never know, alas!

I was wandering about in the cemetery until almost dusk. It’s easy to get lost there, although it is so small, for one is likely to get islanded among the excavations and have quite a little trouble to find one’s way back to the street. There are great holes and ditches and fragments of walls all over the place. At last, trying to find my way out from among a group of newly excavated graves, I was assaulted by a poltergeist. I don’t know how else to explain a sudden slight noise at my feet, and a stinging sensation on my leg and a lot of little wet spots on my stocking which looked as if they’d been made by particles of wet clay. I looked around for a mischievous youngster, but saw none. And I rather like the idea of some outraged Athenian soul flinging wet earth at the disturber of his last repose…

I was surprised to find that there are many points in Athens from which one can see the Aegean; not just from the Acropolis or the other hills. The part of the town that lies between the Acropolis and Lykabettos is rather high. From the plain west and north of the Acropolis one sees nothing but, now and then, the Acropolis or the high peak of Lykabettos, jagged and beautiful and mentioned, curiously, only once in Greek literature. Or so I’m told. Aristophanes mentions it.

The view from the Acropolis takes one’s breath away – or would if the wind left any to be taken. It was funny how familiar it all seemed. I knew without asking anyone just where was Hymettos, Pentelikos, and so on. One is so familiar with the map of Greece and the names of places before one ever comes here. One sees far down the southern coast of Attica, where the Times correspondent tells me the poor of Athens pitch their tents in the scrub forests back of the beaches and spend the whole summer. One sees Salamis and Mount Aegaleos where Xerxes placed his throne to get a bird’s-eye view of the battle of Salamis. And of course one sees the Piraeus and the vast sprawling settlements between the Piraeus and Athens. The two towns have practically grown together. The hardships of life in a waterless town must have been terrible in the days when the refugees were increasing the Athenian population by leaps and bounds. Now the city has an excellent water-supply from Marathon, brought over by an American company. The ship’s doctor coming over told me one could drink it without the slightest fear, but to beware of any bottled spring water outside Athens.

17 November

I’ve been up on the Acropolis looking at the sunset. I learned a lot about Attica. It’s much greener than I thought. Whether it was the sunset light or the clarity of the air that brought out that fact, I’m not quite sure. Perhaps a combination of the two. For the air was clearer than at any time since I came. One could see for an incredible distance. The far southern peaks of Attica, which I hadn’t seen before, were visible and so was Aegina and the coast of the Peloponnesus – is that spelled right? Never mind. It was a curious day. As the sun got ready to go down, the sky to the east was angry and stormy with a rainbow against it. The color effects were superb, but I’m now quite confused. If you asked me what color anything in Attica is, I’d dare not answer. It all depends on the light apparently. The first day I saw the Acropolis, I got the impression that the rock was pink, really more magenta. The next time it looked mostly light blue, with patches of magenta here and there. When I first got up there today, the sky was overcast, as when I was there first, and again the magenta seemed to dominate. And as I looked back at it from the Propylea at sunset, it seemed precisely as if it were covered with snow. And the landscape, too, varies astonishingly in color. I should think this country would enchant and baffle a painter.

The color of the marble of the temples varies a good deal, too, with the light, but not nearly as much, it seems to me, as the earth.

The other day I saw a pile of gravel in one of the streets. It was a lovely pinkish tan. Today I saw a pile of gravel on the Acropolis. It was the palest magenta. I’m obsessed, as you see, with the earth colors of this country; they are so amazing. And no one who has talked or written about Greece has prepared me for them. No doubt writers have described them but none that I’ve happened to read.

This letter is getting very long. I don’t know just how long I’ll stay here. I want to go to some other places in Greece, but how much travelling I can do I don’t know for it’s very difficult and expensive getting places. With lots of time and a knowledge of the language one can get around very cheaply if one doesn’t mind discomfort. Alas! although I have enough time, I don’t know one word of Greek, and I’m not as good at roughing it as I might have been 25 years ago. In Athens one gets along beautifully with French and English. But one needs French much more than English.

When this letter reaches Colfax, perhaps Earle and Beatrice Blew would like to read it. I’ve thought of them a lot since I’ve been here. I send my love to them and to all of you.

Devotedly,

Suzanne

Hotel de la Grande Bretagne

“Le Petit Palais”