The sheep are coming home in Greece

Hark the bells on every hill!

Flock by flock, and fleece by fleece,

Through the evening red and STILL…

— Ledwidge

We are speaking of flokati, of course. On a coast to coast tour of the U.S. some years ago we posed as prospective buyers and visited many places that sell flokati rugs. We listened to sales clerks who knew nothing about their production spin fantastic yarns astonishing to hear in some of the most famous stores in America. Magazine editors, meanwhile, seem unable to distinguish their sheep from their goat and insist on describing flokati as being made from goat’s hair. Still others believe they are made from lamb’s wool — which is too short for shag rugs — or that they are the skin right off the poor sheep’s back!

The confusion about flokati is not, however, restricted to foreigners. Those living outside the areas where they are produced frequently know very little about their manufacture and the tall tales woven by some dealers for the purpose of selling poor workmanship have not helped the situation.

For those who may still be in doubt let it be stated: flokates are, very simply, shag-type carpets made from pure wool fibres which have been spun into yarn, woven and looped together, and then processed under water.

Originally made by the mountain peasants, flokates have remained over the centuries a product exclusive to Greece. To be the only people to fashion something from sheep’s wool and water — raw materials available in most countries — takes some ingenuity. Why none of the millions of Greeks who have migrated all over the world through the centuries have not carried this craft with them is a mystery.

The first flokates were used in ancient times as wall coverings to keep out the bitter mountain winds. Ordinary sheepskins were used to cover the floor. In the Middle Ages the craft grew until it became a major item for barter — sold or exchanged for shoes, kegs of wine, silver jewellery, gold trinkets and Turkish carpets for the very rich. As their value came to be recognized by those making them, flokates became a valuable item for the prika, or dowry.

How many flokates a girl had stored away in her Hope Chest became more important than her charms: beauty after all, is too soon gone, but flokates last a lifetime!

The major factor in processing flokati is water and its weaving became a village industry in those areas where water was plentiful. Some of the best are still produced in Thessaly outside of Trikala, and it is well worth a weekend trip to see them made in their natural surroundings.

Today flokati is made with a mixture of Greek and New Zealand or Australian wool, normally 60/40 or 70/30, the higher percentage being the imported wool. The latter is whiter, fluffier, and softer to the touch. You can test this for yourself if you are in a store which has natural — fisiko — grey and brown rugs because these are all-Greek wool. Local wool, however, is very strong so that the combination of the two is one of strength and beauty.

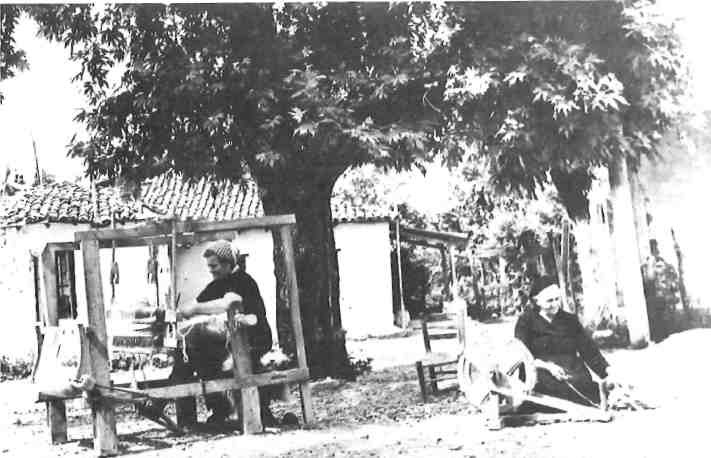

The process begins when the two types of wool are placed in a carding machine which pulls the fibres apart, fluffing and mixing them. The wool is then spun on special hand spindles which form the yarn: this method is unique because unlike most yarns which remain a tight thread once spun, the flokati yarn Opens’ in the waterfall, much like a Japanese water flower. To prevent twisting, the yarn — after

spinning — is boiled and then strung on trees to dry.

Three yarns are used to produce the rugs. Of these the warp, the yarn that is stretched vertically across the loom, is no longer hand spun — not even for handmade rugs — since it has no effect on the final appearance. The second yarn is called the woof or filler and is woven horizontally across the loom. Together these make up the backing of the rug. As each yarn is woven back and forth it is pushed very tightly against the other by the shuttle bar. The third yarn which is the shag (the pile on an ordinary rug) is pre-cut into strands seven or eight inches long. These are looped over the woof as it is being woven. As a row of the woof is filled with looped strands more rows are woven into the loom, more strands are looped through and so on.

The quality of the flokati is determined at this stage, since, with one exception which we shall explain later, the quality of wool used in most rugs is the same. The closer the rows, the heavier and thicker the finished rug will be. If strands are looped, for example, through every three rows, the flokati will be twice as thick as if looped over every six.

An ordinary flokati hand loom is about one metre wide so that the finished panel is never wider than 90 cm. Larger rugs are made by sewing these woven panels together. Customers unaware of this often think that a rug sewn together in this fashion is somehow inferior. When sewn well before being placed under the waterfall, the seams are almost invisible underneath, while from the top they are undetectable. When machine-made flokati first came on the market some were deliberately woven in narrow panels and then sewn together to give the illusion of handmade rugs. Flokati can be woven any length and, of course, occasionally one sees it in stores in huge rolls from which the desired length is cut.

Once the flokates are removed from the loom and, if necessary, sewn together, they are taken to the waterfall for the final processing. The waterfalls are made by diverting natural mountain streams into flumes which carry the water to covered chutes. Wide at the top where they receive the water, the chutes are narrow at the bottom so that the water funnelling through is forced out at considerable pressure.

The chutes are over three metres high and pour down a stream into a round, wooden tub creating a whirlpool. With the water churning and foaming it looks like a witch’s cauldron although the water is cold. From above it resembles an enormous old fashioned washtub, but in fact it is coneshaped causing the cascading water to whirl around and around, tumbling the flokates like the clothes in a washing machine. Every few hours the flokates are hooked out with a long tree limb that has been cut where the branches fork giving it a shape similar to a shepherd’s crook. They are immediately returned to the tub. This is a difficult task because the water-soaked flokates are heavy — but it is an essential step if the rugs are to shrink evenly throughout.

There is a narrow overflow channel leading away from the tub. Several metres along this channel pine tree branches are placed, overlapping each other. The hundreds of tiny twigs catch and hold the fluff as it is washed off the flokati. The longer the rugs are allowed to tumble under the waterfall, the more wool is lost. This is one reason some producers remove the rugs from the vat as soon as possible. The ‘lost’ wool also accounts in part for the difference in price per kilo between the various qualities.

The fluff caught on the pine branches is not used for pillow stuffing or otherwise discarded, however. It is reprocessed and again woven into flokati which do not compare, naturally, with the others because the fibre is too short to wear well. Many of them look very beautiful until they are washed at which time they develop mangy spots.

The best flokates are left in the waterfall several days — during which time they are repeatedly pulled out and returned. Once this process is completed they are hung on long lines stretched between trees to dry. In the winter they freeze and hang in the mists like sheets from a ghostly laundry.

Flokati producers do not usually own their own waterfalls and many use the same one. A coloured yarn is tied to the rugs to identify them and is often still there when the rugs are bought.

Nowadays there are many flokates with designs. Some are quite beautiful while others are made up of the most unfortunate colour combinations. Large rugs with designs must be chosen^with care for they tend to overpower everything else in the room.

The first design woven — and for many years the only one — was the Bridal Flokati. This rug was an important part of the dowry because it was placed on the back of the animal that carried the bride to church. Basically it consists of an inner border composed of a continuous series of checkerboards in various colours. It is most attractive when the design is brightly coloured and the rug white. It also makes a beautiful bedspread. With any design rug the yarn must be dyed before weaving. Solid colours can be made by dying the yarn or the completed rug, but this is a rather tricky process because the final colour is not the same as the one seen in the vat. Therefore I never recommend a do-it-yourself-dye job — at least not for flokati!

There is no denying the beauty and sheer luxury of flokati. A rug, especially these days, involves a considerable investment, but properly looked after flokates will last a life time. How to choose yours and how to care for them? We will have advice and hints for you next month.