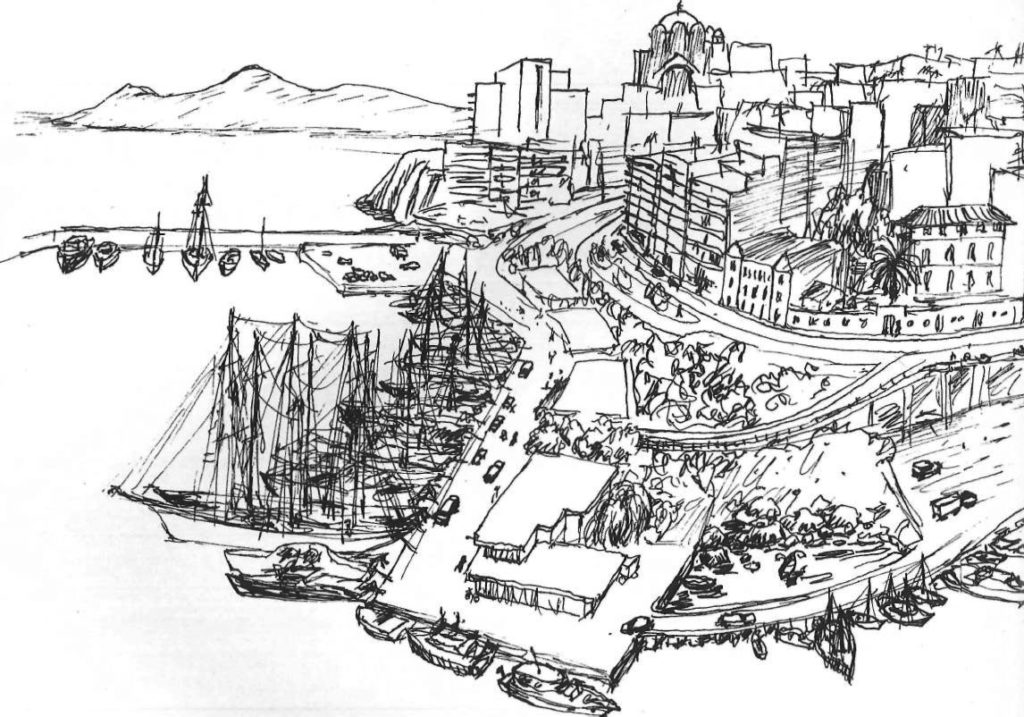

In ancient times it was called Zea, but was renamed Passalimani during the Turkish occupation. The Turkish pasha used to anchor his flagship there. The ‘pasha’ became ‘passa’. ‘Limani’ means harbour in Greek. Thus, Passalimani. Striking a blow for things classical, the entire complex — the inner and outer harbours — is now officially called Marina Zea. But the name Passalimani persists when referring to the tear-shaped inner basin.

Passalimani is a safe harbour in most weather, though strong southerly seas breaking over the wall of the outer harbour can do surprising damage. A few years ago somebody’s motorcar was lifted bodily by huge waves and dumped into the harbour, to the astonishment of its owner and the confusion of the insurance company. The insurance people doubted that the policy covered a car flung to the bottom of the sea by a watery act of God.

Then there was the big ship last year that whacked a shipsize hole in the outer wall on a foggy day. When questioned in court as to whether or not his radar was functioning, the captain immortalized himself by replying that yes, he rather thought so, but everybody knows that radar doesn’t work in a fog.

Some old sailors remember Passalimani in the 50’s, with the 18th century marble stairs leading from the north side of the harbour up to the clock, where before the seawall was built, you could be hurt when a southerly wind blew. In 1947 the sablaritsa caiques still used to unload sand from Salamis by the clock stairs.

Now it is a modern harbour, more or less. Yachtsmen can lay on electricity, telephones, milk and ice without too much trouble. Old Manoli and his cohorts control the keys to the water taps under the quays. Manoli gets whiter every year, hair, skin, and all.

Being large and modern, the harbour is also somewhat less than clean, in spite of all the efforts of balding Barba Yanni, who collects rubbish in his dinghy and once in a while fishes out something nice for some particular friend.

Up to the 5th century BC Piraeus was a boggy marsh — the mosquitoes must have been something stupendous, as even their DDT-nourished descendants are fairly impressive. Faleron, Aegina, and Corinth were much busier and more comfortable ports.

Themistocles, after some shrewd political manoeuvering, was the first to use Zea as a harbour. When a rich vein of silver was struck in the mines near Lavrium around 483 BC, Aristeides, ‘the Just,’ led a conservative move in the assembly to have the yearly surplus of one hundred talents doled out to the citizens. Themistocles countered: under the pretext of an ongoing war with Aegina he demanded that the money be used to build a fleet. A more probable explanation would be that Themistocles, with far-sighted understanding, realized that the Persians had not taken the defeat at Marathon lightly and would be back — in force.

The deadlock in the assembly over what was to be done with the talents was settled by a vote of ostracism. And so Aristeides was banished and the half-finished shipyards at Zea began to produce triremes at the phenomenal rate of one hundred per year.

Passalimani loomed large in the lives of the many generations of embattled Greeks. Lysander, king of Sparta at the end of the Peloponnesian War, tore down Piraeus’s city walls and part of the Long Walls in 404 BC. The Thirty Tyrants sold the ships’ berths to Sparta at the bargain price of 30 talents. New, they had cost 1000 talents.

A little construction continued during all the destruction. A Skeuotheke, an arsenal for rigging, was completed near Passalimani in 329 BC.

Today family life flourishes at Passalimani — dogs, cats, kids, a barbecue on the dock once in a while, a lot of neighbouring. You rarely learn someone’s surname because personalities and boats dominate the scene. Thus it is Richard and Mary of Ruanda, Nick and Pam of Artemis, Hano and Iris of Lutin and so on.

Stuart and Emily live aboard Gay Vandra with their two children. Where -ever there are two children there are likely to be more. At one point the first quay west of the clock tower became known as Childrens’ Quay.

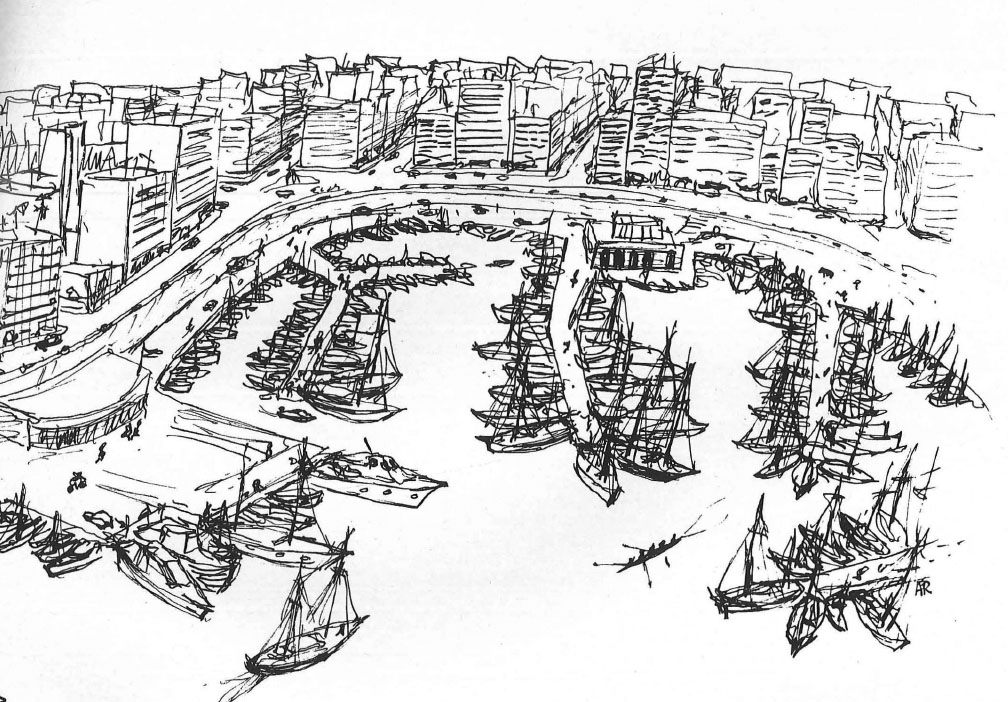

Some of the most beautiful boats in the world are there: the elegant Stormvogel, of round-the-world cruising fame; the Spkit of Cutty Sark, a winner of the single-handed trans-Atlantic race; the Nefertiti, an America’s Cup 12 meter sloop. The famous ocean racer Ondine has called at Zea in recent years. The Greek navy training ship, Eugenia Eugenides, a splendid schooner, is in the outer harbour most of the time.

The ‘Plum Pudding’ is where the boat set meets to gossip, where Tom Phillips sells a waterglass full of wine for 10 drachmas and jobs and scandal are swapped. The ‘Plum’ has cut a little into the trade of the ‘Landfall,’ the other sailor’s bar, where Phyllis reigns and collects news for her column in the Ship’s Log, a fortnightly paper which competes amiably with the new yachting paper, Capstan. As the Capstan is a giveaway paper, the competition isn’t even lukewarm, especially as the staff of both are friends and neighbours.

The yachts this summer are quiet. The fountain in the square (which is, of course, not square — why is there no English equivalent of platia or plaza or piazza?) is cool and lovely, and the promenading couples who fill the quays on a summer’s evening look cheerful and relaxed. Passalimani with her face unwashed still draws a crowd.