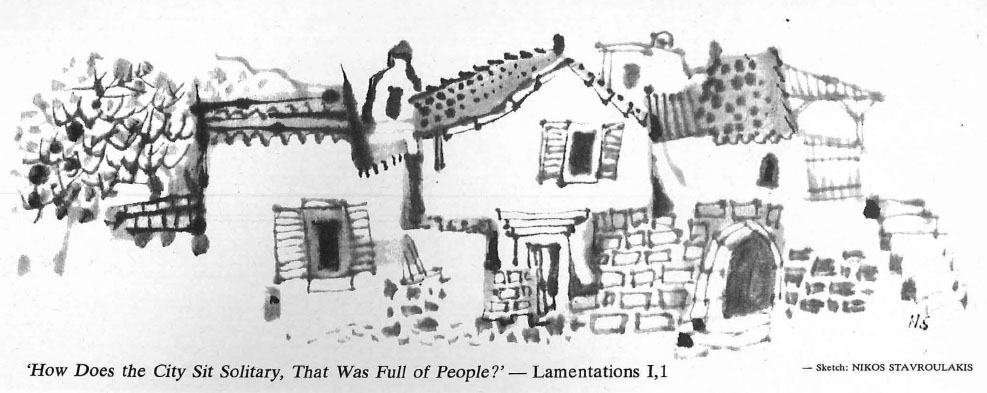

Only the fringes of the Quarter seem to have been affected by the changes and events of the past 50 years or so. The process of erosion inevitably takes its toll, as the new town gradually eats into the area, but the centre remains becalmed, timeless, wrapped in deep introspection.

The back of the Quarter is formed by one of the Venetian ramparts, the Lando which has been all but stripped of its stones. Today the Lando is more like a large earthen mound that stretches haphazardly and without apparent logic along the back of the harbour area. To the west and east, the Quarter is bounded by two large streets. The eastern one, on which can be found the old Venetian church of St. Francis, is today a sort of artery through which the tourists pour — as well as the more modish Chaniots — on late summer afternoons to sit in the cafes and restaurants along the waterfront. The western street, lined with old Venetian and Turkish houses, leads to the Xenia Hotel.

Within this roughly defined rectangle is a small maze, formed by the crumbling facades of old Venetian houses with pretentious Latin inscriptions over their lintels. Here and there appear small doors with finely incised and pointed groins that once led into family chapels. Drawn to a Turkish fountain, one finds next to it the base of a minaret and adjacent to that a house which was once a mosque, and before that, a Venetian oratory. The hammam (Turkish bath) of the Quarter is now a coal storehouse. On the spot where Sudanese slaves used to celebrate the cult of one of their Dervish saints, there now stands a new house. Wooden grills and lattices that once hid richly decorated interiors and the mysteries of the harem have all but vanished or have been replaced by gaping windows out of which blare the latest songs of the 70’s. Where the window frames once were the rich veridian of the Muslims, an almost acid blue is de riqueur now.

The Yusuf Pasha Mahallesi, as the Quarter was once called after the Pasha who claimed Chania for the Sublime Porte in the 17th century, is the dessicated and neglected heart of the modern town, and, like most old centres, the Quarter bears the scars and tragedies of the past more obviously and proudly than the joys. The Cretan Muslims have all gone now, deported in the 20’s to spend their days dreaming of Crete in central Turkey. The present inhabitants of the Quarter are newcomers, strangers to its houses; intruders, in a sense, to its history. They live like sojourners, incongruously uninvolved with the buildings they inhabit — or, perhaps, the Quarter itself is indifferent to their presence.

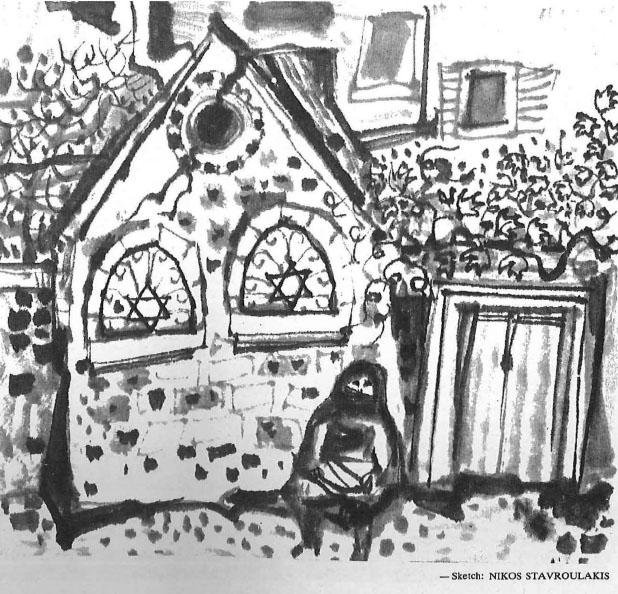

Toward the southeast section of the Yusuf Pasha Mahallesi is a small street with one main exit connecting it to the road that follows the contour of the Lando behind it. Both ends of the street are occupied by houses bearing the catastrophic signs of the German occupation — the houses raked by bullets, their walls pock-marked, broken open, sprouting with wild figs, weeds and lichen. Midway along the street stands a small gabled building flanked on either side by dilapidated walls. A circular window, split by a ragged crack that knifes its way across the facade, occupies the centre of the gable, its finely-chiselled, 15th century frame in elegant contrast to the ruin around it. The northern wall is interrupted by a doorway that leads into a small courtyard, its lintel still recognizably Venetian although across the top runs a Hebrew inscription that reads: Ze-Ha-Sh’ar Leadonai Tsaddikim iavouvo’ — ‘This is the Gate of the Lord, the righteous shall enter into it.’

This building is the only remaining synagogue in Crete, the Kehal Hayyim — the Congregation of Life. Today it occupies what was once a smaller Quarter within the Yusuf Pasha Mahallesi: the Yehudi Mahallesi, the Quarter of the Jews. During the Venetian period, the Jewish Quarter was known as the zudecca as it was then a strictly proscribed ghetto, the Venetians having had little patience with the Jews in their domain. After the fall of Chania to Yusuf Pasha in 1645, the Turks, whose religious vocabulary had no place for anti-semitism, expanded the Quarter and opened the ghetto. The Kehal Hayyim Synagogue, which was to become a sad witness to the last act in the 2000-year history of the Jews of Crete, owes its origin to this period.

At the turn of the 20th century, the Jews of Crete numbered some 2600 — living primarily in Chania, Rethymnon and Herakleion. Some Jews could trace their history back to pre-Byzantine times when Crete and its Jews gave St. Paul such difficulties on his visit to the island. Others were remnants of Jewish immigration from North Africa and still others came later from Spain after the great expulsion under Ferdinand and Isabella.

After Crete was annexed *to the mainland of Greece, the communities on the island began to disperse. Some came to Athens; others went to Palestine; the more venturesome made their way to Paris, London, or America. By 1944, the third year of the German occupation, only the community of Chania continued to function with a total number of 260 souls, one rabbi and a small cemetery. The last seven Jews of Herakleion had been shot in 1943 with a group of Christian hostages, and in the following year Chania and its Jews came within the scope of the Final Solution.

At five o’clock in the morning of the 21st of May, 1944, several lorries quietly came down the street on which stands the Church of St. Francis. The sun was already breaking the horizon and only a few early risers were preparing for the day. Within a few minutes the soldiers and local police cut off all minor exits and the two main ones so that the Mahallesi became the zudecca once again. Its inhabitants, barely awake, were suddenly shocked into the new day by the sounds of doors breaking and the murmuring of confused voices. A few hysterical screams broke the morning stillness followed by sharp orders in German and Greek. Within an hour, the work had been completed: the entire community of the Mahallesi with only what they could carry in their hands was crowded into the lorries.

By midday the Quarter was a silent shambles; clothes, books, odds and ends, that were dropped in the sudden shuffle to the lorries, littered the streets, limply stirring in the hot noonday breeze. Chania had lost its Jews after 2000 years of history, lost them in one morning of ruthless Teutonic efficiency.

Within a week the new synagogue, in use since the 1860’s, was destroyed. The veils of the Scrolls, the tfiHin and prayer shawls of the community and its prayer books were thrown into the smouldering mire of its ruins. The cemetery came next. It was bulldozed and pillaged by-a levy of hostages. The last resting place of the rabbis, who had been renowned for their knowledge of the Law as far north as Vilna and in the Academies of Alexandria in the south, were desecrated, as were those of lesser-known members of the community whose eyes were blessed in not having seen the light of that day.

The fate of those who were seized that May morning was less quickly determined. Their first resting place came at Itz ad-Din, the former Turkish fortress that dramatically overlooks Suda. Here they were taken from the lorries and herded into the old Turkish barracks and cells, where they were kept with scant food and water under the indifferent eyes of the soldiers. On the 7th of June, the prisoners were once again forced into the lorries and taken to Herakleion where they were joined by 400 Cretan civilian hostages and 300 Italian prisoners of war. Here they were all packed into the hold of a small ship, the Danae. It seems most likely that the ship was bound for Athens, where, at Haidari, most of the Jews from the islands were being collected for transportation to their ultimate destination — the crematoria of Belsen. During the night, however, something went amiss and the Danae docked at Santorini. Its German crew and soldiers disembarked and the ship set out for the Cape of Melos with only a token crew and its pilot. Nothing is known of the Danae after that. It never reached Melos. It seems probable that the ship was flooded and sank somewhere in the vicinity of Philigandros carrying 950 souls down into the sea.

Today all that remains of the Chania community — all that remains of the history of the Jews of Crete in fact — is the little synagogue of Kehal Hayyim. Its survival is the only miracle to be found in the last act of its history.

The building can be traced architecturally back to the 15th century when it may have been a Latin Oratory dedicated to St. Catherine. It seems quite probable that when the Venetians were driven from Chania, the church, then standing in the deserted Venetian Quarter, was absorbed into the enlarged confines of the Yehudi Mahallesi. In re-orienting the oratory it was necessary to block up its eastern door, the rough outline of which is still discernible in the wall. This reorientation was necessary to facilitate the erection of the Aron ha-Kodesh, the Ark, in which the Scrolls of the Torah were kept. The building was also shortened, its apsidal end being incorporated into a house. After this the building became the centre of the new zudecca and remained in use until shortly before the war.

The north courtyard is covered by a large vine, the trunk of which betrays its great age. A tradition has it that the original shoot was brought to Chania by one of the 18th century rabbis who had visited Jerusalem. Over the door that leads into the synagogue proper is a small inscription dated Ί52Γ with the name of the benefactor, Moshe Ben Michael Genniti.

The interior of the synagogue is aligned in the typical Sephardi, or Spanish, manner with the Aron ha-Kodesh, its foundation support and heavy hinges still discernible, located opposite the Bema, or reading stand. Indentations in the wall and floor still indicate the proportions of its railings and platform. Above the now empty space where the Ark stood can be seen the ring from which hung the perpetually burning lamp that gave honour to the Scrolls of the Law. There is nothing else. As in the Quarter itself, only mute vacant spaces seem to silently tell their stories.

One can enter the south courtyard of the synagogue through a small door. This open space was formerly covered by a roof and was divided into two floors. The upper floor was the women’s section from which they could look down into the synagogue through wooden latticed screens. The lower floor, one of the walls of which bears the outline of the stair and contains a fine 15th century niche, was reserved for the mikveh or ritual bath. Built according to the stipulations of the Talmud, the mikveh held 40 cubits of water. That it still functions is well testified to by the present inhabitants of the Quarter who complain that periodically it floods into the streets. Perhaps the waters of the mikveh weep in such torrents of sorrow that they cannot contain themselves and seek out those who can no longer weep.

It is very quiet now in the zudecca An old woman occasionally sits in the shade of the building; a white goat nibbles leisurely on a low-hanging ‘muzmulia’ in the courtyard; a voice can be heard calling for ‘Manoli’ or ‘Niko.’ Sometimes the old woman begins to gesticulate at the odd person who stands a bit perplexed by the inscription over the gate. She complains about the ‘ekklesia ton Ovraion’ — ‘the church of the Jews.’ ‘Why don’t they look after it? What a pity it is that they leave it to crumble away.’