Part 1. From a Light Age to the Dark

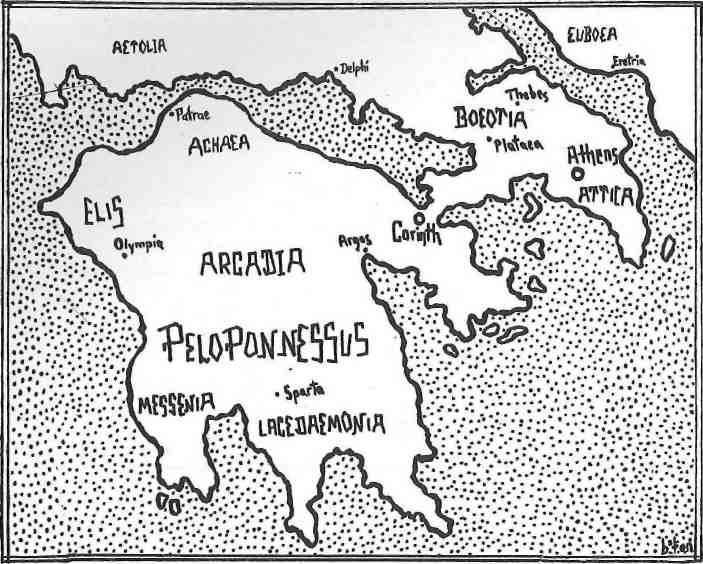

Corinth — controlling the one passage by land from North to South and the one passage by sea between East and West — could hardly help being the chief commercial state in Greece. It also had a small empire to the West (Corfu and Syracuse), while Athens made up for the poverty of its land with wealth secured by a powerful navy, enterprising colonies and a large empire to the East. Power and wealth and rivalry have a way of leading to more power and wealth and rivalry, and the day of reckoning was a matter of time.

In ancient Greece hatred or jealousy were inevitable anyhow between nations only a few miles long (consisting ot a few fertile lowlands locked off from each other by mountain ranges that only soldiers had the energy to cross, or quick-footed messengers, or ambassadors ready to risk anything in times of trouble). Just as inevitably, each city-state developed its own national psychology, dialect, constitution and foreign policy in accordance with its climate, geographical situation and particular economic needs.

In all centuries, for that matter, Greeks have had the courage to admit their hatred and live with it as one of the uncomfortable facts of life. The Trojan War was sparked off by a minor diplomatic incident on Olympos, when Eris, or Strife, was the only deity not invited to the banquet of the gods; and the first recorded incident in the Greek language is a word-battle between two allied chieftains before the walls of Troy. ‘Sing, Goddess, the rage of Achilles,’ is the first line of the Iliad; and that rage takes twenty-four books to work itself out before its end is fulfilled— which, already in line 5, is declared to be the will of Zeus in any case.

No turning of the other cheek, no socially convenient suppression of a basic human instinct, but also no hypocrisy. And in the eighth century BC Hesiod, in the Works and Days, assigns a useful role to a certain kind of Strife in daily existence:

She gets even the lazy to work; for a man grows eager to work when he sees some prosperous neighbour hastening to plough and plant and set his house in order. This Strife is wholesome for men. Arid potter is angry with potter, and craftsman with craftsman, and beggar is jealous of beggar, and minstrel of minstrel….

Athens hated Thebes too, but for reasons of international politics; in 480 BC Thebes took the side of the invading Asiatic army that was clearly large enough to win the war.

Except that it didn’t.

Fifty years later Athens and Sparta detested each other for ideological reasons, as well as for the size of each other’s armed forces. For Sparta, with all its institutions geared to war and the suppression of a indigenous population, and with its flawless heartless rigid and perfectly functioning constitution, it was difficult to coexist on the same land and speaking almost the same speech, with free and democratic and occasionally chaotic Athens. By the middle of the fifth century BC they were the two most powerful states in Greece: Athens reckless; Sparta mistrustful. And Corinth (before the crunch came) trying to do business as usual.

The Athenians had a special temperament, lively and versatile. The one element of compulsion in their form of government was the belief that the State was only safe when everyone took part in politics; the only tiresome officials being those who, at the summons to the ekklesia (the assembly of male citizens over the age of eighteen) to debate, orate and vote on public issues, hurried around town with ropes dipped in red paint to brand anyone who didn’t get there fast enough.

To this condition of almost total democracy there were however a few surprising imperfections: — slavery, imperialism and, alas, democracy itself.

In the ancient world slavery was taken for granted; any army or general or monarch defeated in battle, or people captured after siege were automatically enslaved, whether they were foreigners (‘Anyone not Greek is a barbarian’ was the accepted doctrine) or else Greeks from another city. Yet in many cases slavery was more like a permanent version of domestic service; educated slaves could be teachers to their masters’ children; and — in a world where all that Perikles, for instance, had to say about women was that ‘their greatest glory was to be least talked about by men’ — slaves could be members of a household and treated with the respect due to their former station, or allowed to exercise their craft. Nevertheless their life was described by Aristotle as one of ‘work, punishment and food’, and slave-labour in the silver-mines of Lavrion was no happier than slave-labour anywhere in our own enlightened day. Even among the more democratic of the ancient Greek city-states, although not slave-economies, slaves did constitute up to one-third of the population.

More dangerous for democracy in its Athenian heyday, was imperialism. In 478 BC the Aegean islands and the Greek coastal cities of Asia Minor — (all, be it remembered, self-governing in those happy days before the centralized nation-state existed in the European imagination) — banded together in a protective alliance against the vanguished but ever-dangerous Persians. And Athens was invited to accept the military leadership. History has shown that excessive power is not, in the long run, safe for the holder of it; and by the middle of the century — golden age or no golden age — the Delian League had become a naval empire officially admitted as ‘the cities which the Athenians control’, with Athens extorting the hefty tribute-money that built the Parthenon and other temples destroyed during the Persian occupation of the city; and growing even richer through the prosperous Athenian colonies and military garrisons installed and the reprisals, finally savage, exercised wherever a city rebelled against the increasingly stiff Athenian domination. At the same time, paradoxically, a militaristic and oligarchic Sparta became the champion of Greek local independence.

Yet Athens, on its own territory and in many of its colonies, was riotously democratic; unlike Sparta, it expended most of its energy on other things than war. When the Peloponnesian War broke out in 431, it was Sparta, with nothing else to think about than techniques of battle, and without anything so inconvenient as a political opposition, that was destined to win. But even so, only after twenty-seven years — which says a lot for the resilience of a society that, for all its faults, stayed free to the end.

The pretext for the Peloponnesian War was a dispute with Corinth: a rebellion in its colony, Corfu, gave Athens the chance to come to the aid of an island with a strong naval force. Gradually all of Greece was drawn into the conflict, and in the following century the independence of the separate cities proved weak before another and more crucial test. In vain the Athenian Demosthenes called upon the cities to unite against the growing might of the nation-state of Macedonia to the North. Philip of Macedon’s victory at Chaeronea in 338 transformed Greece into a Macedonian empire, that Alexander extended to Egypt and the Himalayas.

A Macedonian garrison was installed in Piraeus, at what is now the yacht-harbour of Tourkolimano, and Athens had to accept strict modifications of its constitution. Soon it began living off its past. Less freedom, more order, continued prosperity, worse art.

And in accordance with the uniformity that must prevail when a lot of diverse but now enfeebled nations are reduced to a single and parasitic status under one fairly enlightened but military Power, less incentive, less risk, more harmless fun.

Although the Macedonians had not been obliged to exercise the Roman formula of ‘divide and rule’ since their enemies were already sufficiently divided, and although the other Roman formula of ‘bread and circuses’ had not yet been established as a way of governing and keeping people happy through stupefaction, still the energy of individual nations had somehow been exhausted. A series of local rebellions and military leagues between the Greek cities were not enough to throw off the Macedonian yoke, which did, after all, bring law and order to a damaged land, as well as soothe and cater to national pride by spreading the glories of Pan-Hellenic culture into Africa and Asia. The fact that there had never been any such thing as one strictly Pan-Hellenic culture, only a variety of separate cultures, didn’t bother either the Macedonians or their Greek subjects. Enough for Thebes that Pindar could now be read by the banks of the Oxus; enough for Sparta that Leonidas’ valour at Thermopylae should be taught to barbarians; enough for Athens that Sophokles should be performed at the mouth of the Nile; enough for the Thessalians that, some seven centuries before, Achilles had been born to one of their forebears by a sea-nymph; or for Argos that the name of Agammemnon should be known in Afghanistan and Russia. And enough for Corinth (once a power to be reckoned with and famous for her exports of pottery and warships) that a still flourishing city should have become the subject of a proverb in what was now the lingua franca of the small known world: ‘It isn’t everybody’s luck to get to Corinth.’

Corinth was the place for fun — and for perhaps better than the best of reasons; from time immemorial her patron goddess had been Aphrodite; and a corps of sacred prostitutes performed her mysteries in the temple dedicated to her on the mountain towering above the city. The proverb was a realistic and less sentimentally aesthetic version of ‘See Naples and die.’

And yet the Alexandrian Empire kept running into difficulties. Life had become boring for its subjects. Not everyone likes uniformity or even a pax alexandrina. There was a nostalgia for a braver and more warlike time. There were rebellions from below and struggles for succession at the summit. The age was notable for the bitter-sweet, exquisite and existentially hopeless degeneracy that Cavafy, at the beginning of our century, recreated for his own world-view, still curiously compelling even in translations of his poems.

And to the West lay Rome — still provincial but lean, hungry and unscrupulous. The Eastern Mediterranean world had been sufficiently united under the Macedonians for the Roman legions to absorb it. Gradually. Inexorably.

The first step in the process of absorbing Greece was to declare it free. A Roman consul proclaimed the Greek cities’ liberation from the Macedonians at Isthmia, near Corinth, in 196 BC. Fifty years later, when some of those cities showed signs of challenging a foreign protectorate that was showing itself rather more than protective, another Roman consul completed the subjugation of Greece with the total destruction of its richest city — not before packing off the art-works. And about fifty years after that, yet another Roman consul sacked Piraeus and Athens during a war against Persia when the Athenians thought to use the twilight independence left to them, and took the losing side. In vain they tried to draw the consul’s attention to their glorious past, the fifty years (480 – 430 BC) when everything had happened: — Marathon, Parthenon, Sokrates, democracy, tragedy, comedy, etc. The consul replied that he was in Athens to punish rebels, not to learn ancient history.

After that, and for another five centuries or so, a quiet little university town was all that remained of the city whose fame, in the words of Chateaubriand, once equalled that of the entire Roman Empire. Meanwhile, Athens’ rival, Corinth, came to life again when, in 44 BC, Julius Caesar settled a colony of his veterans on the site of the ruined city, and commerce between four points of the compass began inevitably to move again. The independent political life of the city-states however was a thing of the past now that the world was ruled by one State only.

In the early years of the Christian era Athens and Corinth were notable (though largely to theologians and believers of later centuries) for the risky proselytizing visits of St. Paul described in the Acts of the Apostles, and for the two Epistles that he wrote to his negligent converts.

In Athens he tried (a learned Hebrew whose wealth and position had elevated to the rank of civis Romanus) to beat the Athenians at their own game of sharp philosophizing; preaching the Resurrection of Christ first ‘in the synagogue with the Jews, and with the devout persons, and in the market [Agora] daily with them that met with him. And some said, What will this babbler say? other some, He seemeth to be a setter forth of strange gods. For all the Athenians and strangers which were there spent their time in nothing else, but either to tell, or to hear some new thing’; and secondly among the high court judges of the Areopagus, ‘but when they heard of the resurrection of the dead, some mocked: and others said, We will hear thee again of this matter’. One of the judges was converted; Dionysius the Areopagite, who became patron saint of Athens.

In Corinth Paul was luckier and stayed there a year and a half, practising his trade of tent-maker with a colleague, and converting Corinthians and Jews, until the more persistently orthodox Jews had had enough of him and brought him before Gallio, the Roman proconsul, on a charge of something like treason against the State religion. But ‘Gallio cared for none of these things’ and even left the Corinthians to beat up one of the synagogue officials.

After Paul left Greece, word reached him indicating not only that the Corinthians, whether Greeks or Jews, were cursed (or blest?) with the same disunity of opinion that has always been a motive force in the affairs of the South Balkan peninsula, but also that Aphrodite had by no means abandoned her favourite city. The two letters from St. Paul to the Christian community in Corinth, rapping them on the knuckles for their dissipation, drunkenness, quarrels, marriage break-ups, conceit, pomposity and disrespect for the intervention of the miraculous in life, contain some of the world’s finest religious writing (‘Though 1 speak with the tongues of men and of angels, and have not charity, I am become as sounding brass, or a tinkling cymbal….’), as well as some of Christianity’s more unhealthy rubbish (all that gloating approbation of old maids, bachelors, virgins, widows!) that were to affect directly the religious and hence political history of a later Europe, chiefly during the sixteenth century, to say nothing of the agitation over divorce in Italy today.

For centuries however the two cities had little in the way of history. The danger to the Empire was largely external. After Mummius had razed Corinth to the ground in 146 BC and dismantled the citadel, Rome ordered the dismantling (in case of any local aspirations to other than Roman law and Roman order) of all the fortresses that had once guarded the narrow boundaries of the former independent states. In 267 AD the external danger showed itself in Greece with the descent from the Rhine via the Black Sea of a Germanic tribe, the Heruli, who sacked both Athens and Corinth.

In Athens during the fourth century AD the schools of philosophy and rhetoric were still rowdy centres of pagan learning, with Plato’s Academy and Aristotle’s Lyceum still functioning, and the very ancient mystery-cult of Demeter still being practised at Eleusis only a few miles away. But Christianity had caught on; from a religion appealing to slaves, women, the world-weary and the oppressed, it had spread to all sections of the population and been adopted (which wasn’t bad politics) as the official religion of the Empire.

Meanwhile control of the vast Imperial borders was weakening: Athens and Thebes had to be refortified.

In 395 Alaric led his horde of Vizigoths into Greece, ravaging and slaughtering all the way to Piraeus. But (in the words of the contemporary historian, Zosimus) as Alaric came against the city walls [of Athens] with all his host, he beheld Athena Promachos pacing the battlements such as she is figured in the statues, armed and ready for attack, and high upon the walls likewise Achilles, just as Homer has described him at Troy when he came forth in his rage to avenge Patroklos’ death, Unable to prevail against the vision, Alaric halted all operations against the city, offering it peace instead. And he entered the city with a small number of his followers and was received with all manner of courtesy, and visited the baths, and sat at table with the most prominent of the citizens. When he had received their gifts, he withdrew from the city, doing it no harm, and from the whole of Attica. In terror of the apparition, Alaric left all the land in peace, and proceeded against Megara and took it, and then went on into the Peloponnese, meeting no obstacles. Gerontius allowed him passage across the Isthmus, and every town was easily to be captured. For they were without walls, trusting to the protection which the Isthmus gave them. First Corinth was taken, then the smaller towns around it, then Argos. And Sparta suffered the fate of all of Greece, thanks to Greek avarice, undefended by either arms or fighting men, but given up by its commanders, who themselves were both traitors and in everything conducive to public calamity, willing tools of those governing the State.

Athens itself is described at the same period by a Greek from North Africa, Synesius, who came to study at the schools of rhetoric, where the professors were mostly foreigners — Syrians, Arabs, Armenians, Cappadocians and others from Asia Minor.

…May the accursed ship captain perish who brought me here! Athens no longer has anything sublime except the country’s famous names. Just as in the case of a victim burnt in the sacrifical fire, there remains nothing but the skin to help us to reconstruct a creature that was once alive — so, ever since philosophy departed from these precincts, there is nothing for the tourist to admire except the Academy, the Lyceum and, by Zeus! the Decorated Porch, and this no longer decorated, since the Proconsul has shipped away the panels on which Polygnotos of Thasos once displayed his skill. Athens was once the home of the wise: today only the bee-keepers bring it renown. Such is the case of that pair of Sophists in Plutarch who drew the young people to the lecture-room, not by the fame of their eloquence but with pots of honey from Hymettos!

Another of the last pagan students in Athens, Eunapius, describes the end of the thousand – year – old Eleusinian Mysteries, and the end of an era too:

…The name of him who was at that time hierophant it is not lawful for me to tell. He it was who, in the presence of the author of this book, foretold the overthrow of the temples and the ruin of the whole of Greece. He clearly testified that after his death there would be a hierophant unworthy to touch the hierophant’s high seat, because he had been consecrated to the service of other gods: in that one’s lifetime the temples would be utterly destroyed, and the worship of Demeter and Persephone would end. Thus indeed it came to pass. For no sooner had that priest of Mithras become hierophant than without delay many inexplicable disasters came on in a flood. Then it was that Alaric with his barbarians invaded Greece by the Pass of Thermopylae, as easily as if he were traversing an open stadium or a plain suitable for cavalry. For this gateway to Greece was thrown open to him by the impiety of the men in black raiment, who entered Greece unhindered along with him.

In 435 the rest of the prophecy came true, in the Imperial decree of Theodosius II:

We interdict all persons of criminal pagan mind from the accursed immolation of victims, from damnable sacrifices, and from all other such practices. We command that all their fanes, temples and shrines (if even any now remain entire), shall be destroyed and purified by the erection of the sign of the venerable Christian religion. All shall know that if any person has mocked this law, he shall be punished with death.

A few temples not destroyed were transformed into churches: the Temple of Hephaistos (still wrongly called Theseion) overlooking the Agora of Athens, rededicated to St. George; while the great cathedral of now Christian Athens underwent a comparatively painless transformation to the worship of the Virgin Mary, from the monument that Perikles had built in honour of the virgin goddess Athena; once called Parthenon.

The final traces of pagan learning in Athens were wiped out in 529 at the acme of Byzantine civilization, when Justinian ordered the closing of the schools of philosophy and law, including the Academy founded by Plato nine centuries before. ‘Nor,’adds the chronicler (John Malalas) in the next sentence, ‘was dice-playing to be allowed in any city. For in Byzantium those who were discovered playing at dice had their hands cut off, to the tune of dire blasphemies, and paraded about the City on the backs of camels.’

While building in Constantinople the greatest church in Christendom, Justinian proceeded to rebuild walls at strategic points of a land that was now its most neglected province. Prokopios his biographer tells how he refortified Thermopylae ‘and also made safe all the towns of Greece that are inside the walls there; in every case rebuilding their defences. For they had fallen into ruin long before, at Corinth because of terrible earthquakes; and at Athens and Plataea and the towns of Boeotia they had suffered from the long passage of time, while no man in the whole world took thought for them.’

Within these walls an uneducated and wretched population waited for new disasters and the further darkness.