There may be some people in Alexandria who aren’t aware that the city is sliding into oblivion. So, too, there may be a Loch Ness monster in Scotland or a yeti skulking in Tibet.

It wasn’t always that way. Two thousand years ago, during the hey-day of a culture we inherit and no longer understand, Alexandria (today’s al-Iskandariyah) was a metropolis, the prima donna of the ancient world. What happened? How did things go wrong? The dynasty that began with Alexander the Great ended with Cleopatra who backed a loser; the smart money backed Rome.

Today the city is neither smart nor picturesque. Lawrence Durrell, author of the Alexandria Quartet, called it the anus mundi. Hardly a trace of the finery in which the Ptolemies decked out Alexandria survives. But its nostalgia is shrewd and amusing. Coming ashore at Ras-al-Tin, I couldn’t help thinking of victims of neurological disorders – migraine, stroke, results of traumatic injuries – who experience peculiar occlusions of the visual field called scotomas. They find themselves staring, transfixed, at a face but unable to see it – and, stranger still, momentarily unable even to remember the idea of a face. In a sense, the visitor to Alexandria undergoes a long, drawn-out scotomic episode. You go around ritually echoing E.M. Forster by saying that we are all Alexandrians now, beneficiaries of its hothouse flowering, but you don’t see what you’re looking at. There is no there there.

Even a rudimentary knowledge of Mediterranean history suggests that Alexandria had a remarkable career. The roll-call is impressive: not only Alexander and Cleopatra, but also Euclid, Archimedes, Ptolemy, Caesar, Mark Antony, Athanasius, Nelson, Napoleon, Mohammed Ali Pasha and the poet Cavafy. It began with Menelaus who got everything wrong. After he had lost Helen, and indeed after he had recovered her and was returning from Troy, a gale blew his ship onto what Homer describes in the Odyssey as “an island in the surging sea by Egypt.”

“What island is this?” demanded Menelaus of a yokel. “Pharaoh’s,” came the reply. “Pharos?” “Yes, Pharaoh’s, Prouti’s.” (Prouti was another title, used in the hieroglyphs, for the Egyptian king.) “Proteus?” “Yes,” said the bemused yokel.

The wind changed, and Menelaus returned to Greece with news of an island named Pharos whose gaffer was called Proteus. Under such misapprehensions did the anus mundi enter geography.

Its entry into history was terrific. By the age of 26, Alexander the Great had transformed (some say destroyed) the civilization of Greece. But he didn’t hate Greeks. In fact, he admired them and wanted to be treated like one. After spending the winter of 332-331 BC in Egypt, he ordered his architect and city planner Dinocrates to build a magnificent Greek city near a small village called Rhakotis.

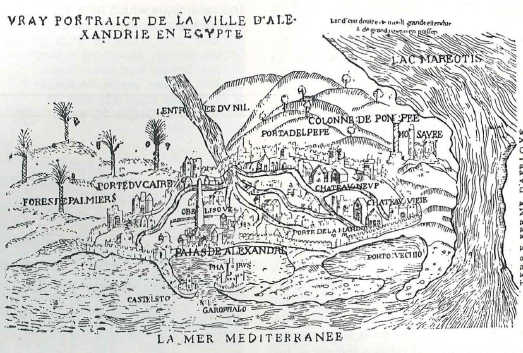

The coastline is flat and featureless so the first thing you notice is sand, the beginning of the desert. It shows up clearly against the blue sea in front and the blue sky behind. Before the Delta of the Nile was formed, the whole country as far south as Cairo lay under water. In the north west an extraordinary spur jutted out. Dinocrates stuck Alexandria halfway down it.

The Nile came out of a crack above Cairo, dumping the muds of Upper Egypt, which silted up against Alexan-dria’s limestone barrier. Alluvial land appeared, and the Nile took advantage of a short cut, escaping into the sea by what was known in historical times as the Canopic mouth.

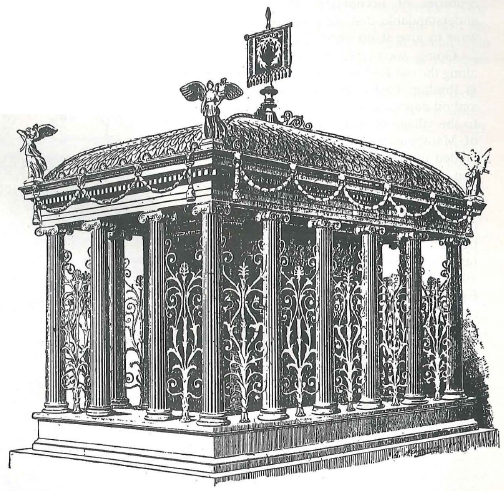

Alexandria was oblong. Its long, white fagade stretched for miles and it still does today. Alexander had Dinocrates lay out the city in zones, in grids. Then he left Egypt and did not return to Alexandria except for entombment: he never saw a building rise.

I had been thinking hard about Alexander’s tomb months before leaving England. Nobody knows where it is. So I got the best maps I could find and, with guidebooks and what bus timetables I could lay my hands on, I tried to imagine where a city would bury its favorite, a tutelary god. The place was called Soma, or body, and the pundits reckon it must have been somewhere underneath Rue Nabi Daniel, below the cinemas and shops and stalls and human flotsam strewn about the jetty. On the way, the bus got stuck in traffic and for an hour and a half it did not move. The hold-up meant walking every inch looking for clues or, worse still, a dangerous nighttime ride along the hairpin bends of the Corniche. Alexandrians are used to waiting for buses that are late, used to travelling on buses that don’t arrive. They don’t complain, but I did. Mohammed, the bus driver, just shrugged. He knew Alexander the Great was down there, too. So what?

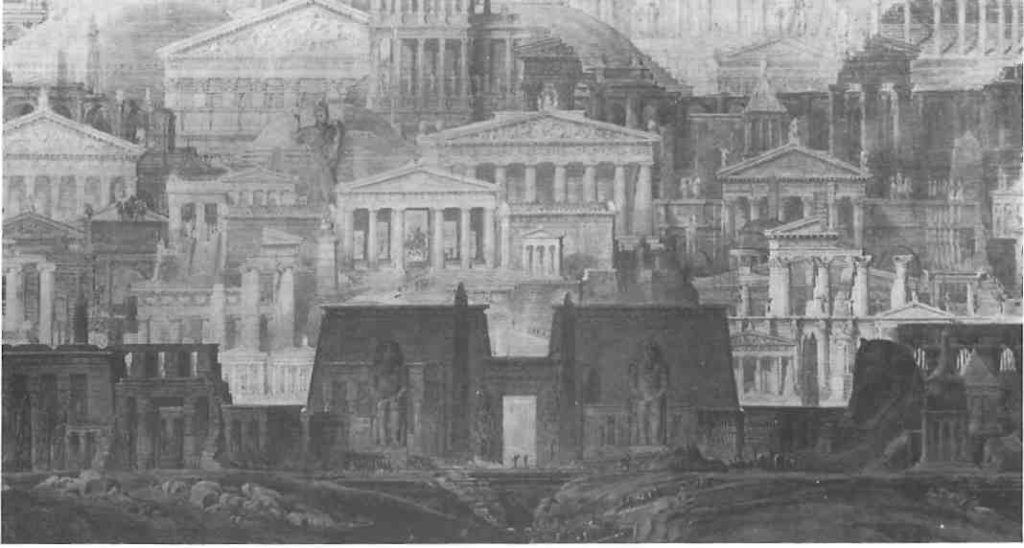

So what if Alexandria disappoints the fraught tourist who comes expect-ing to see the monumental design of Claude Lorrain’s painting in the National Gallery, which shows the Queen of Sheba setting off from a North African port on her journey to the court of King Solomon? Alexandria shone. Its buildings were stuccoed with gypsum of dazzling whiteness. It was no less brilliant intellectually. The Mouseion at Alexandria was the Ptolemies’ great achievement. Not only did it mould the scholarship of its own area: it changed the way we think. Of course, it has disappeared; the site is conjectural (opposite the Soma). Inside were lecture halls, observatories, a park, a zoo, and, most important of all, the Library founded by Ptolemy Soter. The Alexandrian Mouseion outstripped its model in Athens. Mathematics, geography, astronomy and medicine came of age there.

One morning Alaa El Din Ebrahim, a philosopher by training as well as by nature, introduced me to Dr Mohsen Zahran, who has a goal in life – a goal, you could say. He is director of the General Organization of the Alexan-dria Library, a visionary project to rebuild the library as a research institute. Dr Zahran is a peerless fundraiser, but although UNESCO backs the scheme, he is still some way short of his 150 million US dollars target. Dr Zahran cannot understand why. “If you lot in the west had any sense of decorum, the library would go up tomorrow.” He is right, in a way. The advanced countries of the world owe an enormous debt to the advances made by Alexandrian science.

“What to do!” Alaa El Din ex-claimed, rolling his eyes. The philo-sopher believes Alexandria has been neglected and starved of investment. “The tourists don’t come because they don’t know about us. History means nothing. Even our own government has forgotten us. Cairo asks ‘What has Alexandria got?’ No pyramids, no Luxor, no Aswan Dam.”

Alexandria is schizo. It is beset by problems of identity. A pre-Muslim citadel from which all but the Muslims have fled, it has a European past but no European present. Even the physical geography bears witness to a divided self: Alexandria has two harbors, one facing east, the other west. The noise is terrific: the revving of lorry engines, the shunting and uncoupling of railway cars, the clatter of iron wheels and the throaty warnings of ala ra’sak (mind your head).

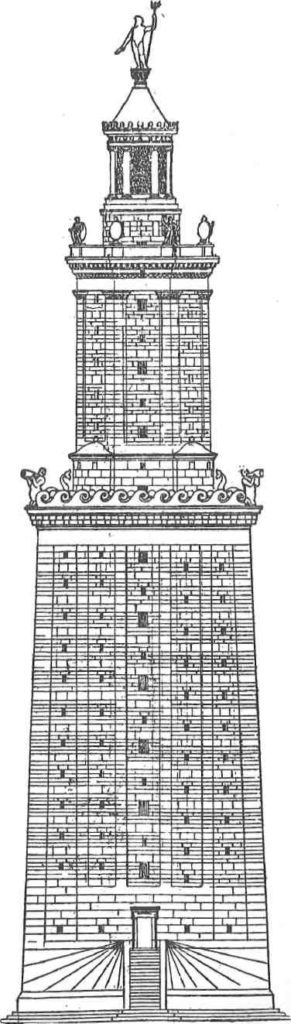

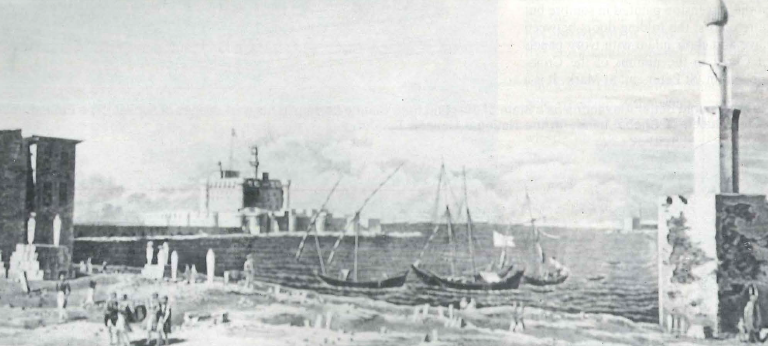

There is evidence of a prehistoric harbor on the edge of the island of Pharos, but no historical record. On the site of what is now the fort of Qa’it Bey, guarding the double harbor, Ptolemy Philadelphus built a lighthouse 400 feet high. Completed in 279 BC, it was one of the Seven Wonders of the World. According to legend, the lighthouse had four storeys. The ground floor was rectangular, with 300 windows. There was a spiral ascent- probably a double spiral- through the octagonal first floor to the circular second floor. The lantern was on top. The lighting arrangements were uncertain. Visitors speak of a mysterious mirror on the summit which was even more wonderful than the building itself. What was this mirror? Was it a polished steel reflector for making a fire or for heliography? Some accounts describe finely-wrought glass or transparent stone and claim that anybody sitting underneath could see · ·invisible ships. A telescope? Is it possible that the Alexandrian school of mathematics discovered the lens and that its discovery was lost and forgotten when Pharos fell?

Pharos was still standing, intact and functioning, when Alexandria fell to the Arabs in 641 AD. The lantern fell in about 700, and the octagon as a result of an earthquake in about 1100. The ground floor survived until the 14th century when it, too, was destroyed by an earthquake. It was called a! Manara (the place of fire) by the Arabs, who adopted the name, and probably the form, for their minarets. Nothing identifiable remains of Pharos, except for a few broken granite and marble columns now used as a perch by fishermen.

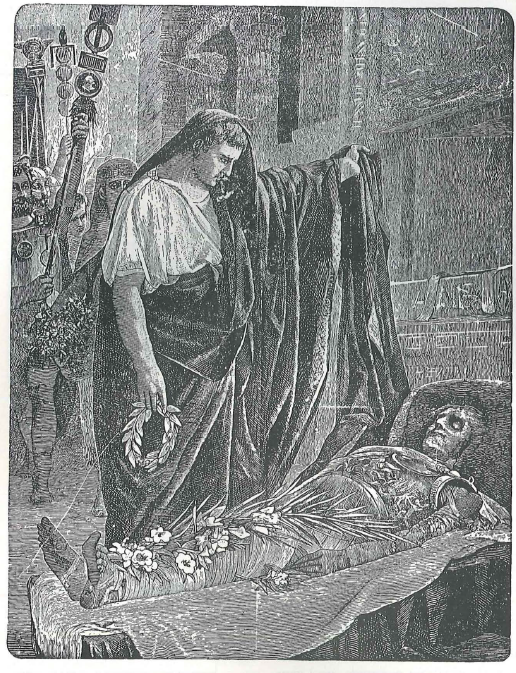

The career of the Greco-Egyptian city ends, as it began, in soap opera. Of course, the Queen of the Nile was a meaner figure than Alexander the Great. Her ambition was purely selfish. Yet the man who created and the woman who lost Alexandria have a monumental greatness in common. The city lacks natural monuments. I looked for the Nile but the elephantine river has also packed its trunk and said goodbye to Alexandria. Alaa El Din told me I had arrived too late, on a geological timescale. The Canopic branch of the Nile silted up a thousand years ago. Octavian (later Augustus) blew the whistle on Alexandria and reduced its imperial function to exporting grain. In the first century AD, however, the triumph of Christianity led to the Copts whose dispute with the established Church was not resolved until the Council of Chalcedon decreed, in the fifth century, that Christ had two natures – divine and human. He was son of God and Mary, but was cosubstantial with God.

Exiles

It goes on being Alexandria still. Just walk a bitalong the straight road that ends at the Hippodrome and you’ll see palaces and monuments that will amaze you. Whatever war-damage it’s suffered, however much smaller it’s become, it’s still a wonderful city.

So Cavafy imagined Greeks in Alexandria some time after the Arabic conquest. They were exiles . .. though it is uncertain from what or where. So, too, Greeks might linger on in Alexandria today … after another diaspora. Yet Alexandria was really never more than a Greek colony in a foreign land, and Hellenes there were always exiles from a homeland left geographically unclear.

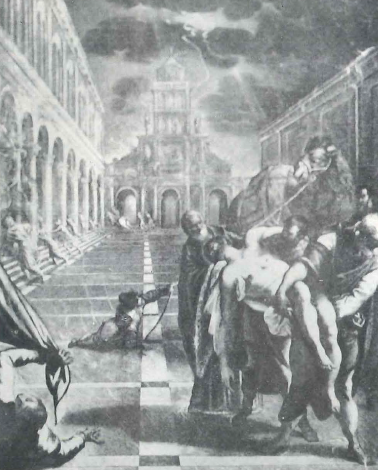

As the minds of the Alexandrians decayed, their heresies became increasingly technical. In most theological disputes, the contending parties agree on a foundation of facts, but in the case of the Monophysite doctrine – that Christ is only divine – the Copts and the Patriarch Theophilus agreed on almost nothing. The Copts claimed their mission was founded by St Mark, who arrived in Alexandria 12 years after the death of Christ. They even ‘built a church on the beach where the Apostle is thought to have been buried before his remains where kidnapped and removed to Venice. The Patriarch dismissed the claim as fabrication. Of Egypt’s 40 million inhabitants, about six million are Christians, and the majority are Copts. The word Copt is derived from the Greek for Egyptian. They point to several monastic ruins, dating from between the fifth and the 11th centuries, that can be found (using bus timetables) in the Western Desert as evidence of their rootedness in the land. From here black-robed monks swarmed into Alexandria to help the patriarch when he wished to extirpate paganism, to threaten him when he wished to conciliate it, and to burn the Library.

The four monasteries at Wadi Natrun , a salty depression on the road to Cairo, are artistic gems. In style, they reveal Egyptian Christianity’s debt to Byzantium. The Convent of the Syrians – a Christian anomaly in Egypt’s Muslim world- is surrounded by high stone walls that emphasize its separatedness.

Because the church of the Virgin has only a few narrow windows, the visitor is in near darkness soon after crossing the threshold. It takes a minute or two to discern a basin for the Maundy washing of the feet, a marble slab with a circular depression.

In the western semi-dome is a fresco of the Ascension painted in sombre but pure colors, the folding doors between nave and choir inlaid with ivory panels of Christ in the nimbus of the Cross, the Virgin, St Peter and St Mark. It is a tribute to the Ottomans that they preserved this Christian shrine during the centuries of occupation. It is also understandable that the Copts do not want to give it up again.

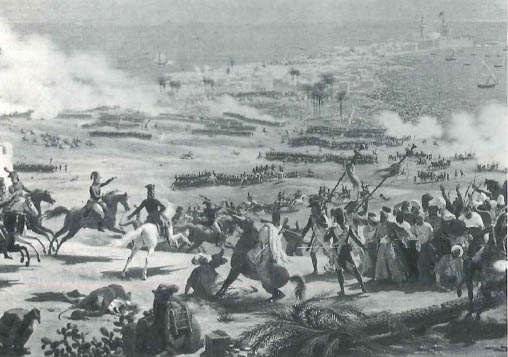

Going west through Alexandria, along the old Rue des Soeurs and Sharia Ibrahim Pasha, passing dock gates and oil depots and abattoirs, you come to the village of Agami and the island of Marabout where Napoleon’s army landed in 1798. Going the other way, you pass through a string of once prosperous resorts, like Ma’amura, now inexplicably ghost towns. The sea is electric blue and unpolluted. The beaches go on forever, and it never rains between March and December. I asked Alaa why the northwest coast of Egypt is depleted of tourists – it is spectacular and cheap, and it is, after all, the Mediterranean – but even the philosopher didn’t know the answer.

Just beyond the promontory is Abuqir Bay, where Nelson fought and defeated Napoleon in 1798. At the Battle of the Nile, one of the decisive battles of history, Britain won command of the Mediterranean and the French Navy received a shock from which it never recovered. Some historians argue that Britain’s imperial adventure can be bracketed between two victories: it made a fine debut at Abuqir and a spectacular exit with the defeat of Rommel’s Afrika Korps at El Alamein a century and a half later.

The Gulf War left its mark on discourse in Alexandria, as it did in most places, the t,rampling of dogma and oil quotas calling forth more passions than can be aroused by the trampling down of lives. In the dusty hamlet of El Alamein, however, an hour to the west, it altered the landscape. The war cemeteries became a gathering place in the middle of nowhere for all sorts of people who appeared to draw strength from remembering the victims – German, Italian, Libyan and British- of an earlier desert storm, whose 50th anniversary was commemorated just a few months ago. War sometimes brings good fortune.

The Rosetta stone, for example, which provided the key to Egyptian hieroglyphics, was found on the beach near Alexandria by an officer in Bonaparte’s army. During the rule of Mohammed Ali and his successors, which began ten years after the Battle of the Nile, Alexandria underwent a . renaissance largely due to Greek entrepreneurs and as a result of becoming ·linked to the interior of Egypt again – in 1819, by canal, and later, in the 1850s, by railway. Cotton spread across the Delta, and owing to the blockade of Southern cotton ports during the American Civil War, Egyptian cotton gained prestige in world markets. The warehouses remain today, but that is all – the industry is gone – and so are the Benakis, the Choremis, the Kazoulis, the Salvages who created it, amalgamated into modern Greece.

On the way home, I stopped by the Roman amphitheatre at Kom ed Dikka, unearthed in 1963, and the nearby catacombs of Kom esh Shugafa, which date back to the early years of the Christian era. Like the catacombs? the Greco-Roman Museum at Midan at Tahrir holds pharaonic relics as well as Mediterranean antiquities. Walking back along the Corniche, beyond the 15th-century Fort of Qa’lt Bey, I took a wrong turning down a back street and ended up wandering through slums near Abul Abbas, a mosque built in 1767 and probably the most alluring of Alexandria’s religious places.

“Alexandria,” wrote Durrell in the Quartet, “would never change so long as the races continued to seethe here like must in a vat.” He was referring to the extraordinary mixture of Arabs, Syrians, Greeks, Italians, Jews and Berbers. During the first half of this century, cosmopolitanism made Alexandria what it had not been since the Arab conquest – a Mediterranean city in its physical appearance, in its way of life and in its cultural and intellectual ambience. The ambience is faithfully reflected in the work of C.P. Cavafy, the celebrated Greek poet who was a native of Alexandria. On my last day in Alexandria I went to the Greek Consulate where Cavafy spent his final, impoverished years, living in a small room among books and papers and memories of “The City”, Wherever I turn, wherever I look, I see the black ruins of my life, here, where I’ve spent so many years, wasted them, destroyed them totally.

It was not a jaundiced view, merely pessimistic. Durrell, on the other hand, returned to Alexandria a dozen years ago, and sat in the lobby of the Hotel Cecil, glowering at the statue of Sa’ad Zaghlul Pasha, hero of the 1919 uprising against the British, and railed against the city for changing.

Until 1960, Alexandria was hardly an Egyptian city. Turning its back on the Delta, as the Ptolemaic capital had done, it looked to the sea. It was clever and ecumenical. Half the street signs were in Latin script, not in Arabic. That is why Alexandria changed: it was unacceptable to a nationalist Egypt. Nowadays Cavafy’s Alexandria has disappeared almost as totally as the city of the Ptolemies. The cotton barons have fled, the poets have dispersed. Villas are shuttered, dubious cafes expropriated, gardens overgrown. The Greeks have left Alexandria, again.

The disappearance of the metropolis was inevitable, even justifiable, but it was also sad. Now amplified mullahs and rich smells of sewers and perfumes fill the market at Tahrir Square where the talk is of Egypt’s debt and a new austerity package – ten percent sales tax, sharp increases in petrol prices and electricity charges – drawn up by the International Monetary Fund. Ironically, the news coincided with the end of the Muslim fasting month of Ramadan, the most euphoric day of the Islamic calendar. The irony is a so.urce of bitterness.

Alexandrians feel victimized when they catch glimpses of the money being invested in Cairo, in the tourist resorts of the Red Sea and Sinai. They deliver a blunt message, in words that have lost some of the tact for which Egyptians are famous.

Others fell victimized as well, but philhellenes still have rallying points. The sea remains. When the Greeks came, they brought something of the Aegean’s lucent quality to Alexandria. Waves curl in the harbor, catching the light . The city draws you into a kind of complicity with itself: it gives off the suggestion of real, human mystery below the surface – a constant sense of something about to be revealed. But, of course, it never is.