A long the road which winds up the hill towards the ancient citadel of Mycenae is the cemetery of the modern Greek village of Mikines. Like any other Greek cemetery, its large marble crosses crown rows of stark, white, raised marble slabs. Each grave has a box which contains a photograph of the deceased, an oil lamp, matches and wicks, and stubs of candles and plastic flowers, evidence of recent vigil for loved ones. The grave of George Mylonas, one of the excavators of Mycenae and one of Greece’s most revered archaeologists, stands proudly near the entrance. He was laid to rest there in the late spring of 1988.

To the right of the little church, and in front of a recently constructed cement fence, stands a modest, yellowing headstone. It is conspicuous in that, unlike the other graves which face east towards the rising sun, it faces south, across the plain of Argos, with a view towards Nauplia and the sea.

The epitaph tells us who is buried there: “Humfry Payne, born in England on February 19, 1902; died in Greece on May 9, 1936; scholar, artist, philhellene”, and, finally, a line of poetry invokes us to “Mourn not for Adonais”.

Who was Humfry Payne, and how did he come to die in Greece at the early age of thirty-four and be buried at Mikines, so far away from England?

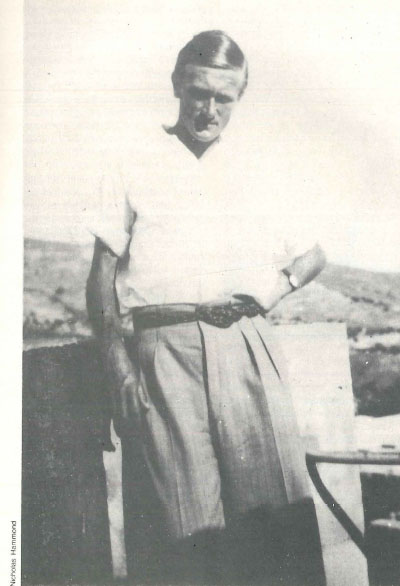

In both the physical and academic sense, Humfry Gilbert Garth Payne can be described as the Golden Boy of British archaeology. He was handsome: six feet five inches tall, slender, and very blond, a striking figure wherever he went. Sir John Beazley, the father of vase-painting stylistic analysis, Payne’s teacher at Oxford and close friend throughout his life, described him as “…square-shouldered, with a small head and small features (except the mouth), fair hair, a fresh complexion, eyes of a strong blue and something boyish, yet resolute in the face.”

A friend once dubbed him ‘Geometric Man’ in reference not only to the similarity of his physique and the elongated figures on Geometric vases, but to Payne’s specialty area of study, Geometric art. Greek children ran away in terror when they saw the apparition of the blond giant, while their mothers crossed themselves when they saw the ‘dyo metro anthropo’, the two-metre man, striding through their village.

Payne’s academic achievements made him outstanding from early youth and are a reflection of the high intellectual traditions on both sides of his family. His father, Edward John Payne, worked his way up from humble circumstances to become a highly respected Victorian intellectual. Edward Payne was extraordinarily gifted and able to master anything to which he turned his mind. He was a classicist, archaeologist, architect, a successful Lincoln’s Inn barrister, Fellow of University College, Oxford, a distinguished historian, as well as an accomplished musician and music historian. Payne’s mother, Emma Pertz, was an artist and the granddaughter of two eminent scholars, James John Garth Wilkinson, the Swedenborgian philosopher, and Georg Heinrich Pertz, editor of Monumenta Germaniae Historica. Unfortunately, Edward Payne died tragically in a drowning accident in 1904, so that father and son were never able to share their common interests in classics, archaeology and history.

Mrs Payne took great care to make sure that the family’s intellectual traditions were kept alive by the three children. She saw that Humfry and his two sisters, Cecilia and Leonora, received the best education possible, despite the fact that they were living on a Civil List pension supplemented by the sale of her paintings. Like his father, Payne’s education was financed throughout by his academic prowess. Over the years he won several prestigious prizes in classics as well as scholarships to finance his education at Westminster School in London, then Christ Church, Oxford, in 1920.

It was during his time at Oxford that Payne first met Sir John Beazley, tutor at Christ Church before becoming Lincoln Professor of Archaeology at Oxford in 1925. When Payne took Greats (literae humaniores) in 1924 he achieved a spectacular First with an ‘A’ in every paper. In this case Beazley was unusually unstinting in the praise of his students when he described the gifted twenty-two year old as “one of the ablest all-round classical men of his time.” Beazley had a profound effect on the young Payne, both personally and intellectually. As Payne’s intellect matured under Beazley’s tutelage, the two became great friends, played tennis together, and wrote to each other regularly until Payne’s death. Bernard Ashmole, also a student of Beazley, said of Payne and his relationship with Beazley, “This was an outstanding mind brought to its finest temper by Beazley’s tuition and example. Beazley never ceased to feel his loss.”

Upon graduation. Payne was awarded the Travelling Fellowship in Archaeology which first brought him to the British School of Archaeology in Athens in the winter of 1924. It was then that his love affair with Greece began. Like so many philhellenes, Payne became enamoured with Greece’s history, antiquities, landscape and people; it became one of the driving forces in his life. As a student at the British School, Payne was serious and dedicated, mixing little with the other students. His interest was in Geometric and Archaic art and as a disciple of Beazley his focus naturally fell on vase-painting. Much of his first year at the School was spent visiting the major archaeological sites and museums of Greece and making notes and drawings of the iconography and style of vases. A study session at the American ex-avations led him to decide on Corinthian vases as his special area of study.

When Payne went out to Athens in 1924 he left behind in England his fiancee, Dilys Powell. Their romance had begun as undergraduates at Oxford and was conducted in the form of escapades and clandestine meetings in the Fellows’ garden at Christ Church. One of Dilys’ nocturnal scrambles over a wall to a rendezvous was discovered by the authorities and both were threatened with being sent down. It was Payne, and not Dilys, who was spared when Gilbert Murray, the famous classical scholar, stepped in to save Oxford’s most promising classics student. Dilys, however, did not get off so lightly. She was rusticated for two terms, during which time she worked as an ‘editor’s dogsbody’ at The Sunday Times. (This was the beginning of her career in journalism and her long association with The Sunday Times- for which she still writes film reviews). She returned to finish her degree, but had to take rooms out of College. She studied hard for her final exams, and graduated with a First in English Literature and French.

After Payne’s death Dilys Powell wrote his biography, entitled The Traveller’s Journey Is Done. In it she paints an enchanting picture of their romance at Oxford during the 1920s: “a conspiratorial trip by night down the Isis to prise a crest off a rival college barge, a night-into-day society whose members dined on Sunday mornings under Magdalen Bridge… the dance-hall out of bounds, the night picnic on the river… It was the heyday of cocoa-parties and chaperons…” The relationship survived the drama of the rustication incident and the couple eventually married in January 1926. Their honeymoon was spent travelling in Greece and Egypt.

The couple returned to Oxford in April 1926 and by the end of that year Payne had ready his first draft of Necrocorinthia: A Study of Corinthian Art in the Archaic Period, a remarkable achievement considering the huge amount of material with which he was working, the speed in which the text was written, and also because he was working full-time as the assistant curator of Coins at the Ashmolean. The draft of Necrocorinthia was awarded a University prize in 1926, the Conington, after being assembled in a frantic thirty-six hours’ sitting. When the book was finally published in 1931, E.J. Forsdyke of the British Museum said in his review of the work, “Mr Payne’s work could not have been better done, and this is one of the few books that justify the claim of archaeology to be called a science. I should say that the excellent drawings seem to be nearly all by the author’s own hand, and that the writing is a work of art.”

Payne gained his first excavation experience in Greece in 1927 when, at the encouragement of Sir Arthur Evans, he excavated the Zafer Papoura chamber tombs located north of the Palace of Knossos. Evans had excavated two tombs in the area in 1907 and found a number of Geometric vases. He asked Payne, now recognized as the established expert on the material, to continue the excavation and then publish the results. Payne started learning modern Greek in earnest while working in the field at Knossos with Evans’ foreman, Manolis Akoumianakis, affectionately known as ‘the Old Wolf. It was said of Payne that he spoke excellent modern Greek, and that he always had a warm relationship with the Greek people wherever he went.

By 1929 Payne had all but finished Necrocorinthia, and his job at the Ashmolean was not up for renewal. A stroke of luck came when he was offered the position of director of the British School of Archaeology in Athens. His appointment was unusual, considering the fact that he was only twenty-seven years old, the youngest person ever to serve as director of the British School. It seems likely that Beazley and Evans had a hand in his appointment as they were both members of the Committee of the British School and their opinions certainly held considerable weight. The Oxford/Cambridge rivalry was alive and well and it was undoubtedly a chance for staunch Oxford men like Evans and Beazley to have one of their own at the helm in Athens. It was also an opportunity for the British School to move away from the usual areas of prehistory and the classical period which people had studied for so long. Payne brought to the job his expertise in relatively untouched areas of study, the Geometric and Archaic periods.

The Committee showed its commitment to change when it told Payne to find a new site to excavate. They gave him carte blanche, and in the spring of 1929 he set out to find a new site. He explored the potential of a number of places, and in May made a journey to Eleutherna in Crete with John Pendlebury, later curator of Knossos, and his wife Hilda,who published an account of it as “A Journey in Crete” in Archaeology. She said of Payne, “He was the perfect companion in wayfaring, and he and John Pendlebury shared a deep love of Greece… Almost two days were spent in this enchanted spot while Humfry Payne investigated the site with a view to future excavation.”

Payne was looking for a site to prove that the chronology of Geometric and Archaic pottery which he had established in Necrocorinthia was correct. Eleutherna did not serve his purpose. He eventually found the perfect site at Perachora, a promontory jutting into the Gulf of Corinth just north of the Isthmus. Of the relationship between Necrocorinthia and Perachora, Payne later said, “I wrote a book, and then I came and dug it up.” Perachora had long been known to the Americans at Corinth and many archaeologists had visited the site and thought better than tackling it. The Pendleburys accompanied Payne, once again, on this trip. John Pendlebury wrote after Payne’s death, “I’m very glad to have known him, particulary on trips. [I remember him saying,]”My God, to think we’re paid to do this!’on a very good day when we had found Perachora and were sitting on the hills above.”

The British School of Archaeology, under the direction of Payne, excavated for four seasons at Perachora, from 1930 to 1933. The finds were extraordinarily rich: little bronze statues of gods and goddesses, animals and birds, exquisitely carved ivories, jewellery and scarabs from exotic lands, and tons of fragments of finely-made pottery, all dedicated to Hera in her temple at the harbor’s edge. Payne died before finishing the text of his Perachora excavations and it was due to the devotion and persistence of his friends and colleagues that it was finally brought to press in 1941.

Those who dug with him at Perachora describe Payne as a striking figure on site. In the days when dour Oxonian greys and blacks were the fashion, it was easy to distinguish his Olympian figure towering above the rest in colorful open-necked shirts of pink and scarlet. Like an expectant father he could be seen pacing from trench to trench, anxiously awaiting the delivery of the next precious object from earth.

Payne’s own artistic talents and his Oxford training with Beazley had endowed him with an interest in and feeling for art of all media. In the autumn of 1933 Payne and a student of the British School, Gerard Mackworth Young, decided to photograph the marble sculptures in the Acropolis Museum in order to publish a visual and descriptive catalogue of the collection. His sensitivity to sculpture, as well as his gifted prose style, are evident in the following passage from the book Archaic Marble Sculptures from the Acropolis:”… I have attempted to keep some kind of balance between the two chief influences which lie behind the archaic traditions: the desire of the artist to reproduce the observed forms of nature, and the necessity which compels him to use a language governed by an order as precise and as exacting as the rhythm of the most strictly metrical verse.” (p.xii)

Payne had an extraordinary visual memory and an eye for detail. It was these two skills that led him to the greatest successes of his career: the piecing together of the scattered fragments of the Aphrodite of Lyons and the Rampin Horseman. While photo-graphing the Acropolis marbles, Payne discovered that the fragments of a kore, a shoulder and part of her garments, were the missing parts of the Aphrodite statue in Lyons. Not only were the pieces with which he was working in Athens the less obvious ones, but he had never examined the Aphrodite of Lyons. A cast of the Aphrodite was sent to Athens and, in great excitement, was found to fit the fragments exactly. Next, he discovered that the head of a bearded man in the Louvre, the famous Rampin head, belonged to the body of a seated figure in the Acropolis. Athenian society soon dubbed him ‘Le Maitre’, but Payne was characteristically modest about his success. In a letter to a colleague he said, “I have been working fairly hard finishing my Acropolis text… It isn’t very grand; meant for beginners, a simple outline of the development of Attic sculpture as illustrated by the marble work on the Acropolis.”

In 1933 Payne and his friend from Oxford, Alan Blakeway, began excavating a small Geometric cemetery on the western face of the acropolis of Knossos. During the second campaign in 1935, James Brock, a student of the British School, assisted Payne and Blakeway, but never managed to discuss in detail with either of them the results of their excavations. After the death of Payne in May 1936, and, most ironically, the death of Blakeway five months later, it fell to the young James Brock to publish the material from the tombs, and the publication is dedicated to the memory of Payne and Blakeway.

In October 1935 Payne travelled to America to give the Charles Eliot Norton lecture series. In a letter to a friend he wrote cheerfully,”… twenty lectures in a month: the last at Bethlehem, which I find is near New York, rather to my surprise. But it will be worth it to see the museums.”

By Easter 1936 Payne was planning to go back to finish excavating Perachora. All the arrangements had been made. Two weeks before excavations were due to begin he played a game of tennis with friends and complained of a ‘bad knee’. In the space of a few days the discomfort persisted, and his doctor treated him for rheumatism. The pain and discomfort increased and he was sent to Evangelismos hospital. It soon became clear that his illness was far more serious than anyone had realized. It was diagnosed as a staphylococcal infection of the blood (commonly known as blood-poisoning), but those were the days before penicillin, and very little could be done to save him. On 9 May, when the moon was full over Hymettus, and with Dilys Powell at his side, Humfry Payne’s life slowly and quietly slipped away.

John Pendlebury was excavating a cave in the Lasithi plateau in Crete when Payne died. In a letter to his father Pendlebury said, “We’ve just heard that Payne has died. How and what of, we don’t know. He was only thirty-five and, apart from bad asthma, about as fit as anyone could be. It will be a terrible loss for the School and for archaeology in general as well as for his friends… [and later] Humfry Payne died of some staphylococcus germ which attacked him in the knee. They took it for rheumatism at first apparently, and gave him massage. We shall miss him a lot. Our friendship throve on insult and abuse. He is buried, I am glad to say, at Mycenae.”

Dilys Powell had Payne buried at Mycenae because it was a place which they both loved dearly. They first went there during their honeymoon in Greece, and managed to go there often over the years in order to get away from Athens and the pressures of Payne’s job. The epitaph “Mourn not for Adonais” is a quotation from the elegy “Adonais” written by Shelley on the occasion of the premature death of the young poet Keats, and is appropriate for another whose spirit lives on in the outstanding achievements of a short lifetime:

“He lives, he wakes – ’tis Death is dead, not he;

Mourn not for Adonais – Thou young Dawn,

Turn all thy dew to splendour, for from thee The spirit thou lamentest is not gone.”

Louise Zarmati is Assistant Archivist at the American School of Classical Studies. She is currently writing a biography of Humfry Payne