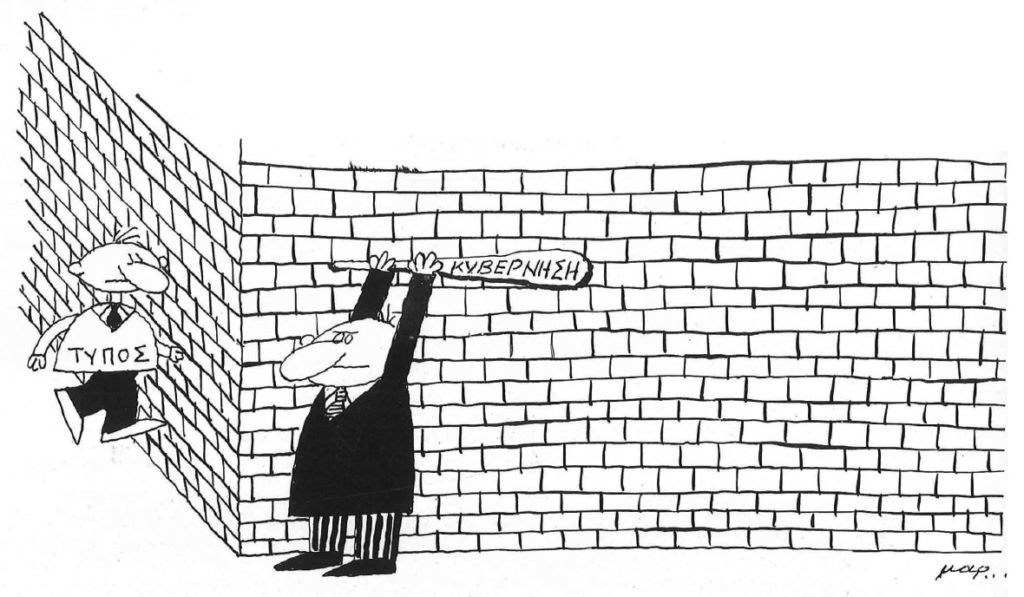

It is often said that the press, internationally known as the ‘fourth estate’ or ‘fourth authority’ is in fact the first authority in Greece because of the political and financial influence wielded by the powerful press barons. So, judging by the major clash which broke out last month between the government – purportedly the first estate or executive power – and the press establishment, what is at hand, by all accounts, is a ‘Battle of the Giants’.

The dash arose over the long-drawn-out dispute as to whether or not the press should have the right to republish the proclamations of terrorist organizations. The government’s argument in enacting such restrictive legislation last year was that such coverage provided “unwarranted publicity” for terrorists and therefore encouraged them to continue their activity.

As proof of the government’s determination to push through its plans, the editor of one of the largest circulation newspapers was arrested in June and an arrest warrant issued for the publisher, iri the first real application of the new legislation. On this occasion, the paper disregarded a prosecutor’s order banning the publication of a proclamation by the notorious ultra-leftist ’17 November’ group, a manifesto designed to explain the reason for its latest business targets.

The very next day, the publishers and editors of six other major newspapers were also charged with violating the same ban, after republishing the same proclamation. They were not arrested, however, and their trial was set for a later date.

The development immediately gave rise to a major political storm between the conservative government and leftwing opposition, as well as among the media.

Specifically, Serafeim Fintanidis, editor of centre-left daily Eleftherotypia, was arrested hours after his newspaper violated a district attorney’s ban by publishing the proclamation by ’17 November’.

At the time of his arrest, Mr Fintanidis told journalists that his paper had always opposed the legislation and that he consciously violated the ban “in application of our firm belief that we are serving the freedom of the press and the right of the public to be informed.”

The Greek government countered that publicizing terrorist proclamations was a major form of encouragment for them and perpetuated the terrorism problem that is plaguing the country.

The drive to enact the legislation last year was headed by Deputy Minister to the Prime Minister, Mrs Dora Bakoyianni, Mr Mitsotakis’ daughter whose husband was murdered by ‘November 17’ two years ago.

Under the legislation, newspapers are allowed to give full coverage of terrorist actions such as killings and bombings, but a state prosecutor must decide whether or not they can subsequently publicize the boasts and ideology advocated through their proclamations.

Penalties foreseen for the print media include the arrest of editors and publishers and fines of up to 100 million drachmas, and in the case of radio and television stations similar fines and even their complete closure.

The arrest of the editor caused a major political storm. Provisions against the press have provoked strong reactions from left-wing parties and newspapers, on the ground that they curtail press freedom . The opposition socialist party, led by former prime minister Andreas Papandreou, charged that the arrest and the other prosecutions constituted “government terrorism” that .was personally ordered by Prime Minister Constantine Mitsotakis.

The government denied any involvement, calling on the press and political parties not to interfere in the course of justice. Minister to the President, Mr Miltiades Evert, summoned a special press conference· and accused the press of “unacceptable conduct” in encouraging the violation of the law.

He said. newspapers carried pages and pages on the case, yet committed the “nationally unacceptable mistake’ of paying little attention to the official and highly significant visit to Cyprus by Premier Mitsotakis that was simultaneously under way.

The Prime Minister himself was even more categorical and, from Cyprus, dismissed criticism, indicating that his government would stand firm on the legislation. “Everyone in Greece,” he declared, “including the prime minister, the main opposition party leader, the parliamentary deputies and ministers, should respect the laws. Newspapers and journalists should do the same and cannot be the exception.”

Meanwhile, reaction from media executives varied. Dimitris Mathiopoulos, President of the Athens Union of Journalists, took a mildly anti-government stand by declaring that “there are strong reservations as to whether this provision is constitutional.”

He qualified this statement by saying that it should be left up to the courfs to decide. Most centre-leftist newspapers, on the other hand, took issue with the Prime Minister over the apparent contradiction between his proclamations to the outside world and his practical moves at home.

Specifically, they pointed to the paradoxes contained in Mr Mitsotakis’ address to the World Conference of Publishers that was convened in Athens earlier in the month, in which he criticized regimes which put any kind of restrictions on the press. Only a few days after that speech, papers pointed out, he imposed the ban on terrorist proclamations, a measure which in Europe is only applied in Ireland and Great Britain against proclamations by the IRA.

The arrested editor himself said that he would “fight the case in court, not only for our own newspaper but for all the Greek media.”

He was released after an initial hearing and his trial was rescheduled. Christos Tegopoulos, the publisher of the paper who is also President of the Athens Union of Publishers, remained at large and managed to avoid immediate arrest and trial. He has not yet commented on his arrest warrant. On the other hand, the conservative media welcomed the government’s decisiveness.

The editor of Greece’s largest circulation newspaper, the conservative and pro-government Eleftheros Typos, described the publication of the proclamation as “blood trade” by Eleftherotypia designed to cash in on a higher circulation that was expected to generated through the general commotion that was caused. Indeed, over the next two days Eleftherotypia’s circulation increased by about 30 percent, bringing it considerable additional revenues.

“By publishing terrorist proclamations we become a public relations office for the terrorists,” said Dimitris Rizos, prominent editor of Eleftheros Typos. “We do not help press freedom as much as we help terrorism. We, in the newspaper business, believe we can easily accept such a minor restriction, when comparing it to the enormous benefit to society and the country as a whole if we succeed in restricting terrorism.”

In the proclamation in question, ’17 November’ explained why it hiid bombed six industrial and business targets over the passed two months, most of them representing European and American interests. The group claimed that Greece’s conservative government was “selling Greece out” to “Western capitalism.”

It particularly objected to US Lockheed Corporation recently obtaining 49 percent of Greece’s Hellenic Aerospace Industry. “As long as this vital industry remains in the hands of Lockheed, no prbper air defence of Greek airspace can exist against Turkish expansionism,” the proclamation said.

’17 November’ has murdered 16 Greek and American officials since 1975 and has also bombed western business targets, especially during the Gulf war as an expression of opposition to the coalition forces fighting Saddam Hussein.

In recent months the Greek government has achieved impressive successes in disrupting a number of Arab terrorist networks and in arresting a Palestinian involved in the 1985 hijacking of the Italian cruise ship Achille Lauro. But it has not yet scored any successes against ’17 November’.