A good part of the general public is not aware of the existence of Greece’s Railway Museum, located right here in Athens. The museum does, however, have its own group of enthusiastic ‘fans’ who would readily admit their affection for the steam locomotive.

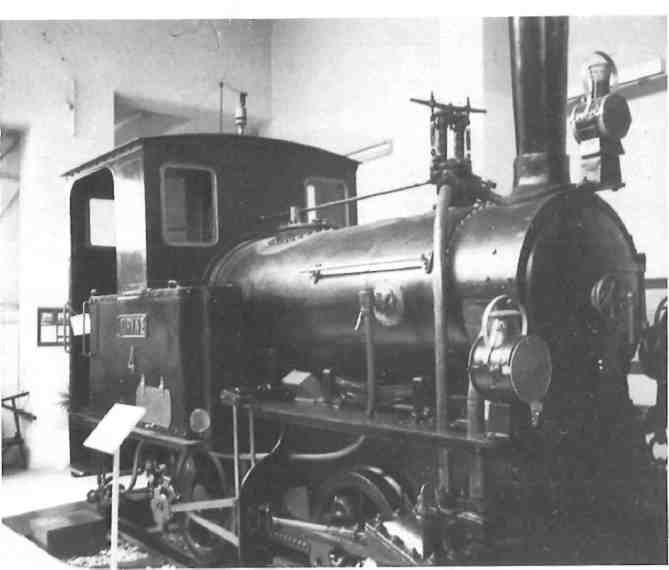

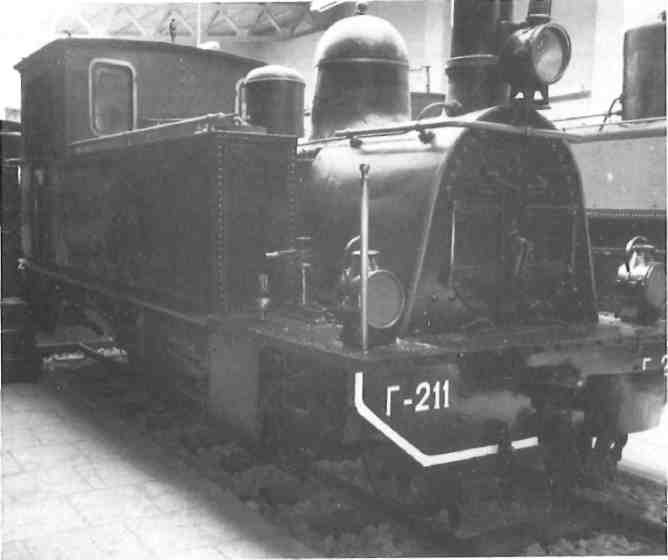

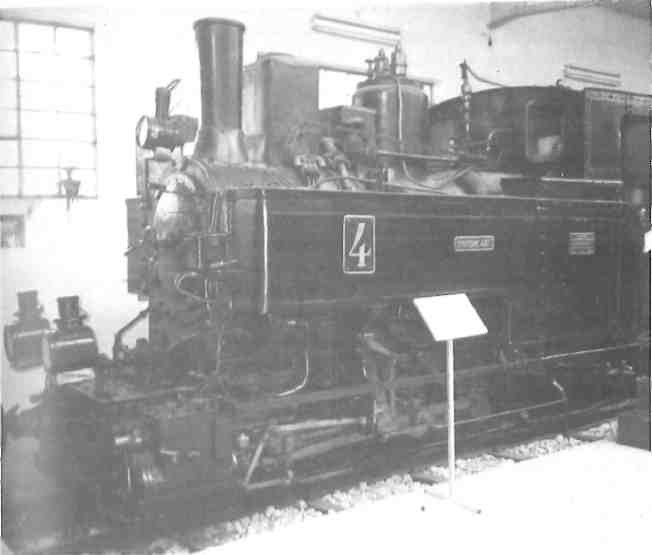

The Railway Museum of Athens holds some splendid examples of these steam locomotives, some dating from the 1800s, all of which are in perfect condition. Rail lines were laid many years ago across great lands: India, China, the USSR, Mexico and the United States. In India and China, steam locomotives still run, but China is the only country left in the world still manufacturing them, as they have ample supplies of coal, hence finding them profitable enough to run.

Inaugurated in 1979, the museum was built and furnished with the financial support of railway enthusiasts and materiel donations from the Greek railroad organization OSE (Organismos Sidirodromou Ellados). When funds are raised for renovation, work is carried out by both museum supporters and experts from OSE. It needs to be mentioned that 90 percent of the enthusiasts have no connection with the railroad in their work.

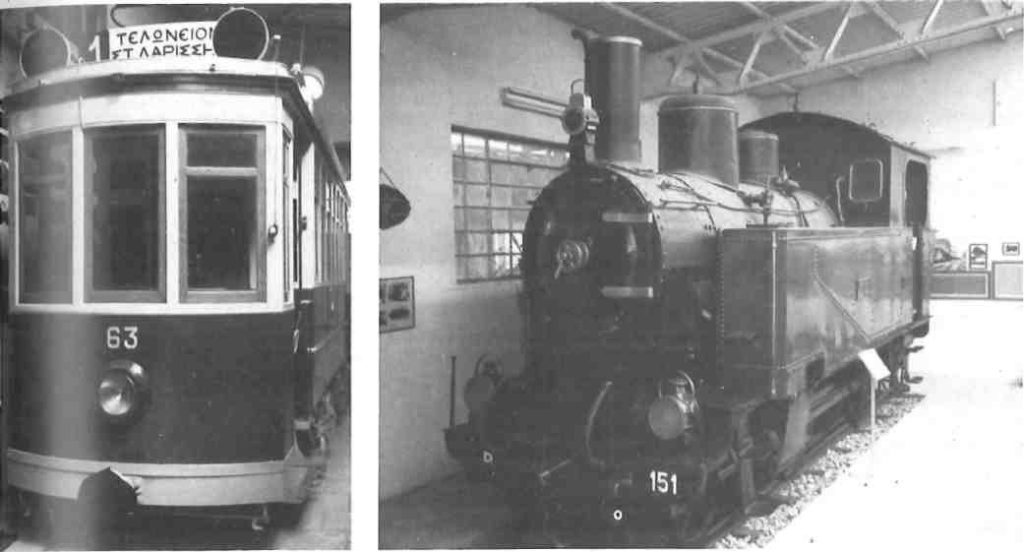

On display in the exhibition are four industrial steam engines donated by OSE, and an 1899 metre gauge (or cog engine) which once made the short run from Krioneri opposite Patras up to Messolonghi years ago.

The personal smoking coach of Sultan Abdul Aziz of Turkey was secured by the Greeks in 1913 when they captured Thessaloniki during the First Balkan War. Built in the middle of the 19th century and presented to the Sultan by Empress Eugenie of France during the rapid expansion of Turkey’s railroad system, the car is now on show in the museum. The car’s parquet floor is hooded by a ceiling of inlaid wood supported by spiraling columns, designed as a sort of open-air pergola. Gilt wrought-iron work in floral ornament and arabesques grace the car’s exterior, and the wheel hubs bear the crescent of the Ottomans.

In one of the exhibition halls, myriad paraphernalia are reunited: conductors’ uniforms, ticket machines, signals, whistles, old station signs and clocks, maps and train itineraries, and telegraphic equipment. There is a display of furnishings from royal coaches, including barometers, menus, wall clocks and mirrors. It is all fascinating, and one can spend hours poring over the various objects.

‘Out in the field’ I was shown a remarkable steam engine that wac once used for industrial purposes in Greece. It was discovered lying neglected in a railway yard. It appears much like a larger version of a child’s toy engine, rusty, however, and looking forlorn. She still lies as found, awaiting sufficient funding for restorative work.

Most engines are given names, and I was told both here and in the United Kingdom by people acquainted with the railroad that engine drivers could ‘understand’ the temperament of an engine just by its sounds and performance, perhaps a clue as to why sexist men referred to them as ‘she’.

‘Train’ in the general language of today means some sort of multiple-bodied vehicle, propelled by mechanized means and running on a strictly-confined track. Ever since the canoe evolved into the ship, this sort of train has done more to change the world than any other form of conveyance. It did for continental transportation what the ship centuries earlier had done for maritime transportation. Although motor and aircraft have since replaced them, ship and train originally opened up the world.

Trains, loosely speaking, are as old as the ancient Greeks. Hero, an Alexandrian Greek, devised a primitive reaction ‘turbine’ as simply a scientific toy. Motive power was furnished by men (or slaves), mules, asses and horses. Steam engines were first used for industrial purposes centuries later, principally in mining. Owing to its rugged terrain but its accessibility by sea, steam-powered ships long kept their edge over railways in Greece, and, excepting Albania, it was the last European country to construct a railroad system.

Public railway systems were first incorporated in the United Kingdom in the early 1800s. France, Austria, Belgium and the United States soon followed. Some of the more famous inventors of early modern steam engines were James Watt (1736-1819), a Scot credited with the invention of the condenser which gave steam greater pressure; and Richard Trevithick, a Celt from Cornwall, who died in poverty despite his many attempts to inspire the public with his inventions. George Stevenson (1781-1848), with his son Robert, are among the names most often affiliated with the development of the steam engine in the United Kingdom. Robert Stephenson became the first millionaire engineer, and when he died at the age of 56, he was buried alongside kings and queens in Westminster Abbey.

Steam trains served the world’s transportation needs for 150 years, and they are still held in great respect by millions of enthusiasts around the globe.

The first Greek railroad line, Siderodromo Athens/Piraeus (SAP) was constructed in the 1850s to connect Athens with its booming port of Piraeus (‘the Manchester of the* Levant’) 10 kilometres away. It began at the present Theseion Station and ended at the glamorous depot still standing today opposite the major Piraeus docks.

It was completed in 1869 and inaugurated by Queen Olga and her retinue with great pomp. The royal passage took 15 minutes to complete.

In the 1880s a new central Athens station was built which has recently been charmingly restored and SAP engendered SPAP, the second ‘P’ standing for Teloponnese1. The narrow gauge line which goes to Corinth and then makes a circuit of the ‘island of Pelops1 still has a tiny station at Mycenae where the legendary figures of early archaeology like Sir Arthur Evans and Mrs Schliemann would descend from the cars with mountains of luggage. Sadly, the train does not stop there any more. A branch from Argos to Nafplion still functions, however.

Twisting up the mountains to Arcadia, then down to Kalamata, up the western coast to Patras and finally back along the Gulf of Corinth to Isthmia, it is one of the longest narrow-gauge ‘network’ still functioning in Europe, and certainly the most beautiful. Just the short rack-railway leaving from Diakofto on the Gulf up to Kalavryta is itself still a great tourist attraction, and right¬ly so.

The liberation of Thessaly in 1878 inspired a standard-gauge railway to inch up from Athens to Larissa over a period of 20 years.

At Pharsala, a little to the south (where Pompey met his end at the hands of Caesar), a crossline was built from the port of Volos up to Kalambaka at the foot of the Pindus Mountains. Last year Patriarch Demetrios I of Constantinople made this trip to celebrate the 600th anniversary of the founding of Great Meteora.

The successes of the First Balkan War joined Macedonia with the Kingdom of the Hellenes and the railway continued its slow progress northwards.

Although it had none of the magnitude of the link-ups between the eastern and western coasts of North America and Australia, the connecting of Athens with Thessaloniki, and, therefore of all Greece with Europe in 1918, was a great moment in the history of the country and its growing ties with the West.

The revival of the Orient Express in recent times, induced by nostalgia and Agatha Christie, began a new period in railroading, substituting for necessary, practical transport an aesthetically delightful experience.

Quite recently I was offered an opportunity for a trip from Vienna to Sopron, Hungary, and jumped at the chance. The engine was built in 1923 and brought out Austrian and Hungarian rail enthusiasts from both sides of the border. I was happy to learn that Austrian Railways now has a regular fleet of old, lovingly-restored locomotives, which embark upon journeys from one evening to two weeks in duration. It is an enjoyable way to see parts of the Austrian and Hungarian landscapes; of course one need not be a railway devotee to enjoy it.

In 1980 some British enthusiasts came to Greece on a special seventeen-day tour of the Peloponnese on the narrow- gauge railway, via steam locomotive. Such trips are wonderful, chugging through the still much unspoilt and spectacular Greek countryside. The Railway Museum, located on Liossion Avenue, not far from the Aghios Nikolaos metro station, is open Wednesdays from 5pm to 8pm, and Fridays, from 10am to 1pm. With the efforts of Greece’s numerous patrons of the railway, what might otherwise be lost, has been, and will be, preserved.