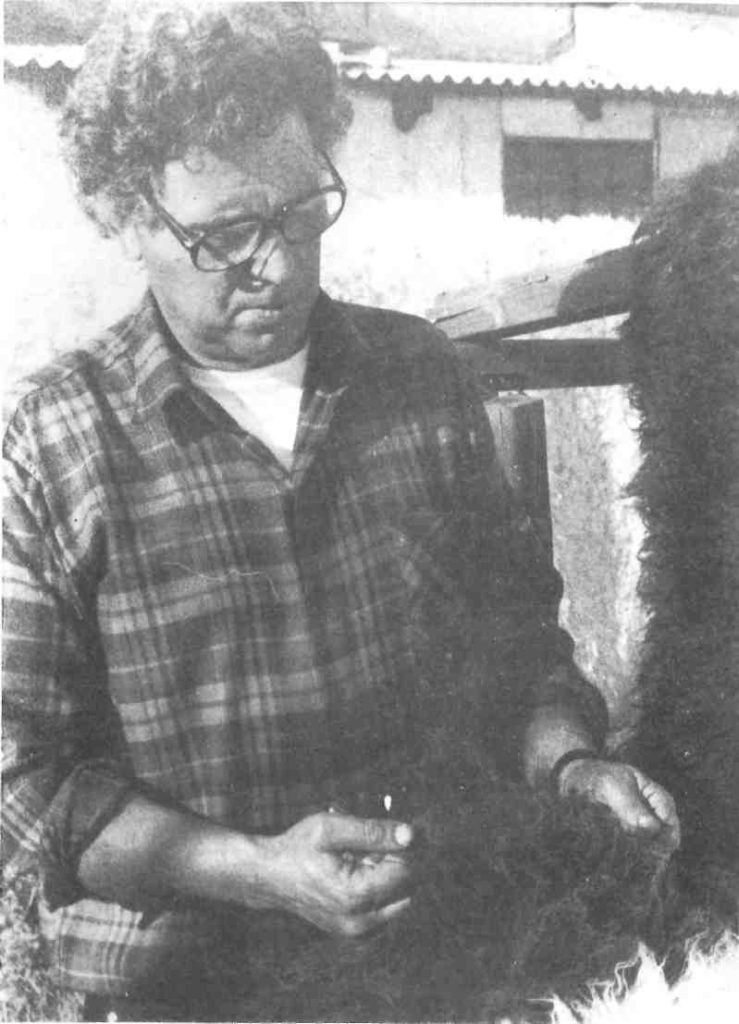

Kyr’ Alekos is a husky, gruff-looking man, with a gentle, patient way and a streak of tradition in his personality, perfect for his kind of work. He runs a small workshop staffed by dedicated artisans just outside Thessaloniki, where the National Highway to Athens begins. He and his employees are committed to preserving a traditional technique of creating a handmade product that modern machine imitations cannot hope to match. The product they make, with painstaking dedication, is the sheepswool flokati rug, and the shop, Shepherd’s Rug, is a business that Mr Alekos Stefas inherited from his father. In the face of cheaper, lower quality machine-made substitutes, he vows to continue the business.

The small staff, who call him by his first name, work not only for the money, but for the pride in turning a mangled bundle of sheep’s wool into a fluffy, 100 percent natural rug that is exported all over the world. With its long, shabby fibers, the flokati is as much symbolic of Greece as are worry beads and Metaxa brandy. Almost every Greek home has one, and, thanks to Mr Stefas and the remaining few like him, the distinctive carpet can also be found in homes all over the globe.

Walking into Mr Stefas’ shop, rather than the whir of machinery or the rattle of large pieces of motor-driven steel moving frantically back and forth, there is the sound of a hand loom, the clank of wood against wood, the soft swish of fibers on iron frames, the deliberate, careful squeak of foot pedals moving rolls of virgin wool. Occasionally, singing breaks out from inside this most human of factories. Mr Stefas prepares coffee while talking about his company. The room is furnished with a Spartan simplicity; a small wooden desk covered with correspondence and stacks of rugs of different sizes and colors rests beneath a plank ceiling supported by heavy wooden beams. Taped up on the walls are letters of thanks, of praise, of new orders from satisfied customers. They come from everywhere, from San Francisco to Saudi Arabia.

Lighting a cigarette and drawing it slowly, he runs a hand through salt-and-pepper hair, and in a calm, smooth voice explains the production process which begins on the other side of the world and ends here with a rug of the highest quality, constituted of the best materials. As Mr Stefas says with sincerity and pride, “here we make a rug that will last a lifetime.”

The wool comes from New Zealand, where it is sheared and shipped to Greece. The wool does not come from Greek animals because they are especially bred for meat, hence their somewhat coarser wool. The New Zealand sheep is fed a special diet and is bred specifically for a wool of high quality. Upon its arrival in Greece, the wool is cleaned and woven into several different thicknesses of yarn. From there it is wound onto several long rolls, each containing many strands of the wool. The rolls are then threaded through the hand looms to be woven into what will become a flokati.

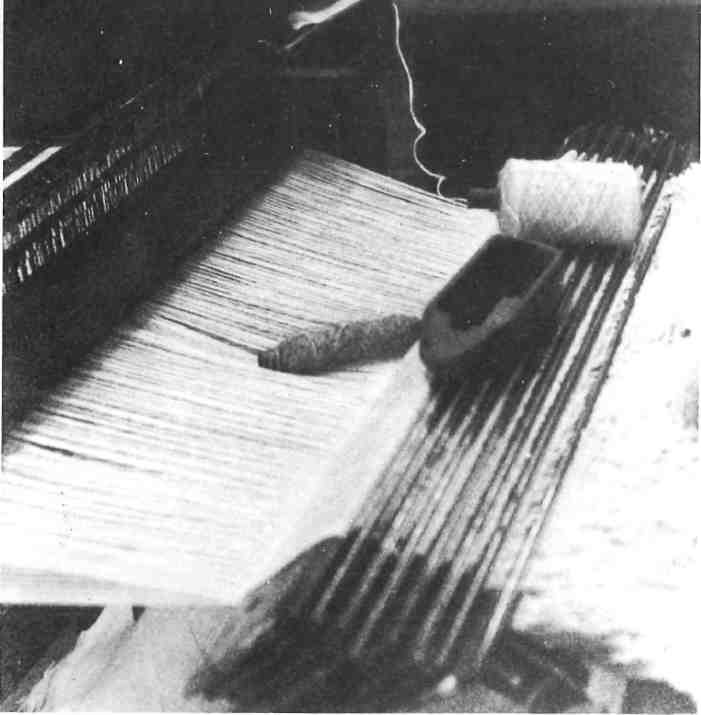

There are two main components of the rug: the pile and the backing. Both are made of the same wool, but the backing is made of a more thickly-woven yarn. Mr Stefas takes the visitor into another room where a flokati is being processed by a mother and daughter on a hand loom. While the daughter stacks several finished rugs, the mother sits on a bench before the loom, working the horizontal rack of yarns at waist-level, while manipulating at her feet a set of wooden pedals that turn the various parts of the loom, threading the yarn through a series of steel eyelets that direct them to the pile and backing. The pile is interwoven into the backing with a series of loops. While making each loop, she passes a small wooden shuttle through the tows of yarn, which carries another thread across the pile to separate and bind it. The motions together create a slow symphony of rhythmic clacks, thumps and whirs as cloth, wood, iron and human hands move together in a coor-dinated, paced motion of stops and starts followed by smooth flipovers and loopings.

This method of production is now rare: only about ten factories still use it, most of them located in northern Greece around Veria and Trikala. The remaining manufacturers produce a machine-made rug which is thinner and has a polypropylene backing instead of wool.

‘This product has been defamed by imitators,” Mr Stefas says, “whose machine-made polypropylene-backed product is significantly cheaper to produce. We refuse to go that way. We use the same quality wool for the pile and for the bottom of the carpet, that is, the best wool you can find. We must show people that we have an industry that is devoted to quality. It takes half a day to weave a rug, but its quality is apparent. You either make a low-quality product or you do the best.”

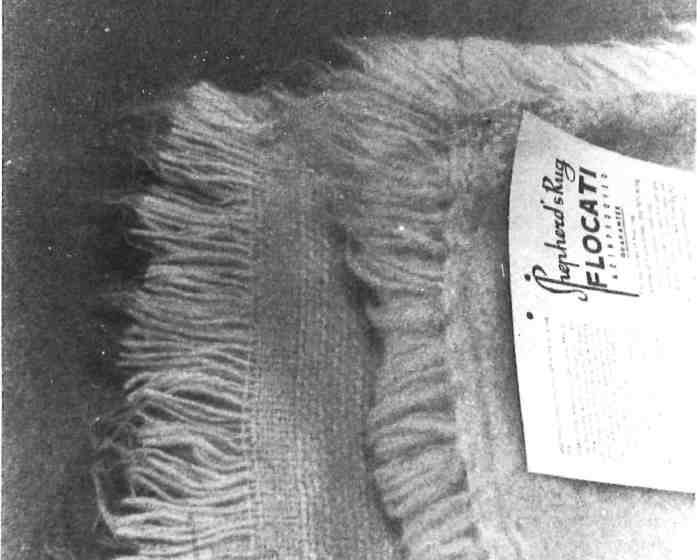

In displaying a machine-made rug next to one of his deluxe model hand-woven flokati, the disparity is striking. The machine-made carpet is barely two centimetres thick, from the thin backing to the top of the pile. But when a hand is pressed down on one of Mr Stefas’ rugs, it all but disappears into the pile. The handmade rug is of a better quality too, characterized by a radiant shine, a pure white hue, and a softness unusual for wool. The machine model is dull in color, coarser and less resilient. The pile is so sparse that the backing can be seen through it. If held up to the window, the light shines through. The handmade model is much denser, both in the thickness of the backing and in the pile. However apparent the difference, Mr Stefas explains, many buyers do not take the time to look for the best quality and simply buy what is most readily available.

As the woman at the loom puts the rug together centimetre by centimetre, Mr Stefas tells me about the ups and downs of the flokati industry since he began in the 1950s. At a time when the people and the economy were reeling from the aftermath of civil war, which ended in 1949, an export agreement was made with a Swiss humanitarian group specialized in post-war economic development. The agency, the Association of the Swiss Organizations for Foreign Assistance, helped set up a program by which women earned in-come by producing flokati in their pets and synthetics.” Soap, water and sun are all that are needed to clean the flokati rug.

As customers affiliated with the bases travelled on, they informed friends all over the world of these unique rugs. With the departure of the bases, however, the market has experienced a downturn. Presently, Mr Stefas, who learned English as a student at Anatolia College in Thessaloniki, frequently invites tour and school groups to come to the shop to observe a living Greek tradition.

At the loom, the woman repeatedly runs the pile through the backing and over six independent wooden planks. Stopping the foot pedals, she takes a special razor, and runs it over a groove

in the top of each of the planks, cutting the pile and giving it the shaggy-dog appearance with which we are familiar. She pulls the planks away, weaves another set over them, and repeats the move. By using planks of different height, she can lengthen or shorten the height of the pile, making it either short and bristly, or long and shaggy.

The weaver gives a personal touch to each rug, controlling the tightness of the backing, the way the pile is cut and the length of the pile. There is even a special name given to this personal touch: tsalimi. Mr Stefas explains tsalimi by comparing it to the way a musician controls a piece of music. “It’s the softness, the spirit that the woman is putting into the instrument. It’s like playing an organ. It’s not only necessary to know the notes; you have to put something of yourself into it. Two rugs made on the same loom, but by two different women, will look different.”

When the weaving is over, however, the flokati is still not finished. Taking a woven rug from a stack nearby, he indicates the spot where the pile loops through the backing. Pulling a strand of the pile, it begins to come out. “Now, the pile comes off easily. So, we have to find a way of tightening the pile with the bottom.” The carpet is therefore run through a river-fed water passage which will effect shrinkage of the carpet, tightening the backing around the pile and holding it firmly. “This, for example, which is now 84 centimetres, will come out from the water 75 or 70 centimetres,” he says. “This is a primitive way of holding the pile with the bottom, because, in the carpet industry, they are always trying to find ways to hold the pile to the bottom. Sometimes they use latex, or try other ways, but what we do is a unique and ‘traditional’ way, because it’s based on the properties of the wool.”

Trucks haul flokati shipments to a water installation in Veria, at a tributary of the Aliakmon River, west of Thessaloniki. They are placed in an outdoor track in the river, using only the natural current of the stream water to process the rugs. They are then trucked back to Thessaloniki, still wet, and put in a steam-heated hot-water tank for about 20 minutes to be disinfected and mothproofed. This done, Mr Stefas and his workers hang the soaking rugs outside to dry in the Mediterranean sun. When dry, they are brought in to be combed and fluffed. Only then is the flokati completed.

Standing in the bright midday light, Mr Stefas concludes “some people see a sunny day and say this is a good day for going swimming. I see a sunny day and say this is a good day for drying flokati.”

Is it Real? How to tell α genuine, high-quality handmade flokati carpet from a cheap machine-made imitation.

Turn the carpet over and look for seams (places where two sections of rug have been sewn together to make it wider). Remember, on a hand loom, the width of the carpet can only be as wide as the span of the worker’s hands, about 70-80 centimetres, because the worker must reach far enough to pass the wooden shuttle through the yarns. If the carpet is more than 80 or 90 centimetres wide and has no seam,.it has been made on a machine.

Hold the carpet up to the light. Does it block the rays or does the light shine through? If it is so thin that the light shines through, it is probably not handmade, and is certainly not good quality.

How thick is it? Is only a centimetre or so its total height? Then it is a cheap imitation. If the thickness is more than four or five centimetres, and up to eight centimetres, you are holding a high-quality rug in your hands.

Look at the pile. Is it nice and uniform? Then it is handmade. If the pile is mangled, it was made on a fast-moving machine, which can mutilate and sometimes even tear the wool.

Examine the texture of the backing. A good handmade flokati will have the same 100 percent wool as the pile, though a little thicker. A machine-made imitation will have a synthetic polypropylene backing.

Do not worry much about the color. Wool can be dyed in any color without harming it. The natural colors, however, are white, brown and grey. If you are examining a white carpet, check to be sure that it is an even, full white, which is a sign that the wool came from a well-bred, healthy sheep.