The recent crisis in northern Yugoslavia has fanned the spark in the Balkans reviving all the old questions and ethnic divisions patched up politically at the end of World War I. The determination of Slovenians and Croats to liberate themselves from what they consider a backward Serbian domination has set in motion an unpredictable chain of events. Now that the referendum for the independence of the Yugoslavian Republic of Macedonia is set on 8 September, it is indicative that ideas from the north have contaminated the south.

Greece has watched the developments of neighboring Yugoslavia with increasing apprehension, not only because of common borders, but primarily because Yugoslavia is its commercial umbilical cord connecting it by land to the European Community. Northern Greece, and particularly the rich provinces of Veria, Naoussa and Edessa that are the main exporters of fruit and vegetables, are particularly vulnerable and immediately affected by the war skirmishes since Yugoslavia constitutes the only outlet for its produce. “The cross-border trade in consumer items has fallen off now, with the complete devaluation of the Yugoslavian dinar,” says Christos Alexiou, President of the Chamber of Commerce in Florina.

Basically, it is northern Greece that first and foremost felt the repercussions of the Yugoslavian crisis, watching a daily decline in the flow of tourists who crossed its borders, even for a daily trip, or to buy Greeks products, from detergents to clothes. The smaller cities closer to the border like Fiorina have been even more affected than the big urban centers like Thessaloniki.

Apart from these economic concerns, a lot of people closer to the frontier are naturally more sensitive to political changes in the neighboring countries, because, as in the case of the Albanian refugees, they are the first to be affected. The fact that some of the people in northern Greece are bilingual, speaking a Slavic idiom has no particular significance, although both Skopje and Sofia have contradicting theories about what constitutes Macedonia, with lobbies mainly in Canada and Australia. Sofia’s is the older one, dating from over a century ago, while Skopje’s only dates from the creation of its new Republic in 1945.

Athens is not particularly anxious about the referendum in Skopje, judging that an independent Republic of Macedonia will be ineffective and incapable of viability in the midst of so many incongruities. The fact that Greece has very friendly ties with Serbia and has maintained good neighborly relations with Yugoslavia is a positive factor. The Greek government spokesman, Vyron Polydoras, has said “it is an internal issue of Yugoslavia” and refused to make any further statements.

Bordering Greece on one side and Bulgaria on the other, the southern part of Yugoslavia will find it very difficult to survive as an independent republic because it will have to balance an odd mixture of restless ethnic minorities with different religions. Bulgaria and Yugoslavia are locked in a long-standing dispute over Macedonia. Apart from its consistency in having an explosive nature, the republic’s economy is in complete shambles. Any financing from the outside world seems most unlikely with all the simultaneous autonomous movements that have broken out. Yugoslavia’s economy has been in a tragic state with a steady decline over the past years, and Skopje has never been particularly affluent.

Apart from ethnic Turks, there are a lot of Moslem Albanians in Skopje and the Saudis have also tried to alleviate their economic plight by pouring in money to support their faith.

This part of southern Yugoslavia was chopped off and formed into an artificial republic, mainly in order to balance the overpowering presence of Serbia. It was a political act conceived by Tito in 1944 who first gave it the name Macedonia the following year. The second step was the upgrading, to the class of a new language under the same name, of a group of dialects spoken in the geographical area of Monastir-Skopje-Perlepe. Over a Slavic gramatical skeleton with a lot of Turkish words and newly-imported French words needed to fill the gaps for new notions, the ‘language of Skopje’ was born.

In northern Greece, there is a fundamental difference in the spoken dialect due to the large percentage of Greek words and a significant percentage of Vlach words that constitute the vocabulary. Nonetheless, it allows Greeks to communicate with Yugoslavs of the border areas in simple everyday words restricted to a basic grammar. A lot of people in the area have called it

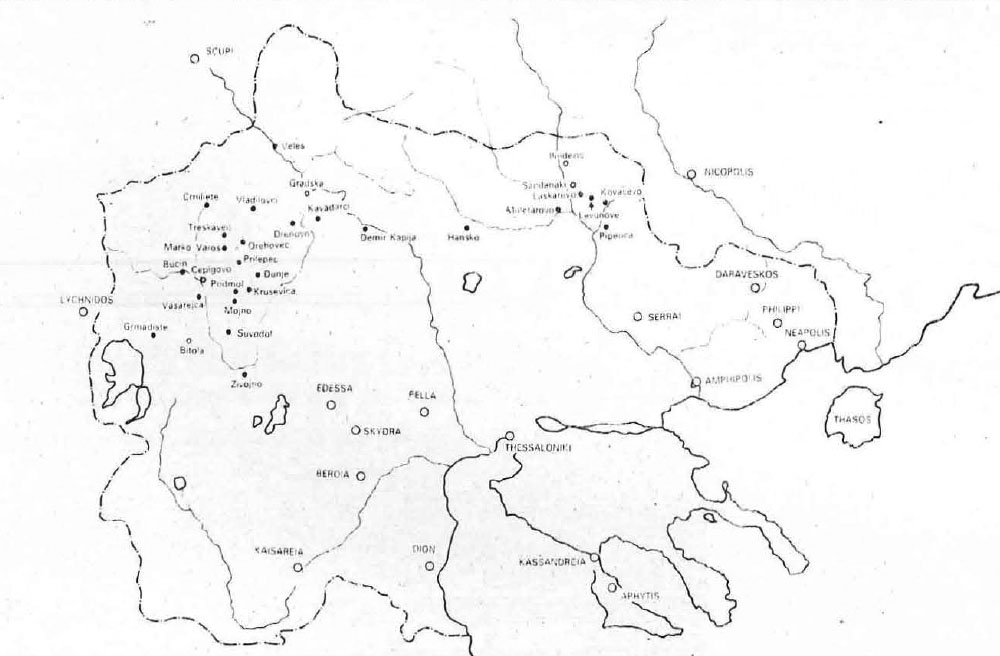

Bulgarian, and due to this and the fact that many in the area declared a Bulgarian orientation, there were exchanges of populations between Greece and Bulgaria, the first in 1924 under the Politis-Karlov Agreement and the second in 1928 under the Kafantaris-Molov Agreement. The Treaty of Bucharest in 1913 delineated the then existent borders of Macedonia giving 51.1 percent to Greece, 39.5 percent to Yugoslavia and 10 percent to Bulgaria.

The communists later created a theory for a Greater Macedonia which the Greek Communist Party endorsed in its 5th Plenum in 1949 at the end of the Civil War. Later, in 1956, they rejected these positions, but some diehards of these theories still exist among a handful of people in Greece who can find no new platform of ideas. Many believe that they are used as agents by Skopje. Yet it is in Canada where Skopje has its strongest lobby, and from there, various theories are spread about a Macedonian identity, with funding even paid out among some people in Greece. “It may be to the advantage of Greeks if Skopje becomes independent because it will clear the air about the historical inaccuracies once and for all,” says a western diplomat.

In 1957 the federal state was renamed the ‘Socialist Republic of Macedonia’ and in June it became the ‘Republic of Macedonia’. The Bulgarians, however, had appropriated this area much earlier when the first signs of a geographical interest appeared on the horizon in the 19th century. The two committees of the Internal Macedonian Revolutionary Organization (VMRO) were first created in Sofia and Resen. Today, the strongest party in Skopje is the VMRO, while a similar VMRO UMO (Union of Macedonian Organization) was created two years ago in Sofia.

Since the overthrow of Todor Zhivkov, Bulgaria has a rekindled interest in the issue. The last high-level bilateral visit was Zhivkov in 1967. Now, Bulgaria continues a low-key support of the VMRO, echoing the old relationship. Skopje’s effort to gain independence has created serious doubts about its success even in Yugoslavia. The questions of the referendum on 8 September, about autonomy, sovereignty and remaining part of a newly-negotiated Federal Republic of Yugoslavia, are contradictory in themselves. Yet the people will be asked to ‘ cast their ballot and make a decision that, according to a foreign diplomat, “opens the doors to questions and problems rather than answering them.”

The European Community has reacted anxiously and has taken quick decisions to avert further developments in Croatia and Slovenia. They are the richest and most developed parts of Yugoslavia. Above all, they were once part of the’Austrian Empire and, therefore, much closer to Europe historically. But the attempt of Skopje to hold a referendum on independence does not fulfill any of these qualifications.

Yet, even Slovenia and Croatia have not been welcomed into the arms of Europe, although Germany’s softened attitude has angered the French. The Americans, sensing the reluctance of a united European front to allowing them to play ball in their own court, has jumped to declare, as George Bush stated, that it is a ‘European question’. But this time it was not the Gulf War, and the EC has been decisive not to let the US move onto its own turf. The Balkans, all know, is a difficult area but political analysts believe that Washington is very interested in the area despite its claims and “would not miss a chance to have a footing under any guise because they do not like seeing en bloc a solid European front,”

Divided between East and West, with Slovenia and Croatia part of the Hapsburg domains and the rest part of the Ottoman Empire, Yugoslavia is the epitome of the Balkan problem. The attraction of wealthy neighbors incited the urge of Croatia and Slovenia for independence, and the pull of a united Europe has acted as a catalyst. Skopje would like to follow its rich northern brothers, but unable to flirt with Europe, Kiro Grigorov, President of the Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia, in an act of weakness, visited Ankara in July to discuss regional issues.

Turkey likes to play a hegemonic hand in the area reminiscent of Ottoman rule. In this, she is supported by a large minority of ethnic Turks existing in Bulgaria and a hundred thousand in Skopje. But Bulgaria shares borders with Turkey,and Ankara, with its foreign policy at its lowest ebb, made a miserable faux pas with the minority in Bulgaria. Closing the borders to the ethnic Turks whom President Ozal had invited with open arms to the mother-land three years ago, did not set a good precedent. Ankara, however, seems undaunted, and Skopje is too far away to dampen fears on both sides.

Apart from ethnic Turks, there are a lot of Moslem Albanians in Skopje and the Saudis have also tried in the past to alleviate their economic plight by pouring in money to support their Islamic faith. Even so, these are not compatible groups, even though they share the same religion.

The Ottomans left a difficult legacy in the area with their millet system of dividing population by religion rather than ethnic origins. It became an almost impossible process to disentangle the issues from the chain of nationalist movements and the Balkan Wars. Today, Europe is not willing to see a repetition of previous wars, and the political framework has changed together with our understanding of the historical word ‘ethnicity’.

Once more the Balkans are in flux with two currents juxtaposed. One aims at breaking existing countries into smaller units. The other, working at the same time in a parallel way, tries to unite into a greater Europe. It is the strongest which sets the rules, and Skopje, in its narrow nationalism, does not stand a chance.