Ρera Palace Hotel has not changed since the Belle Epoque of the city when it was the natural termination of the Orient Express. A cup of tea at the Patisserie, served in silver and porcelain, completes the atmosphere of the hotel’s beginning of the century grandeur. In Pera and Galata, a generation ago, one could hear nothing but Greek and French spoken. This is no longer the case, but Pera’s Grand Rue (Istiklal Caddesi or Independence Street) has been completely restored and has become a pedestrian street. The old reclaimed red and white tram is once again clinging its bells from the tunnel to Taxim Square. Walking down Grand Rue, one can still see some of the most beautiful shops in Europe, untouched and preserved as if time has stood still; the buildings in some cases are breathtakingly beautiful: Constantinople at its best.

The reason for any visitor, and particularly any Greek, to be in the city is to visit one of the greatest monuments of Hellenism: the Church of Holy Wisdom, or Agia Sophia as even the Turks still call it. The taste for splendor, the style of rich flamboyant material, and yet the natural and humble existence on earth are as such the new and profound transformation of artistic language for the Byzantine Greeks.

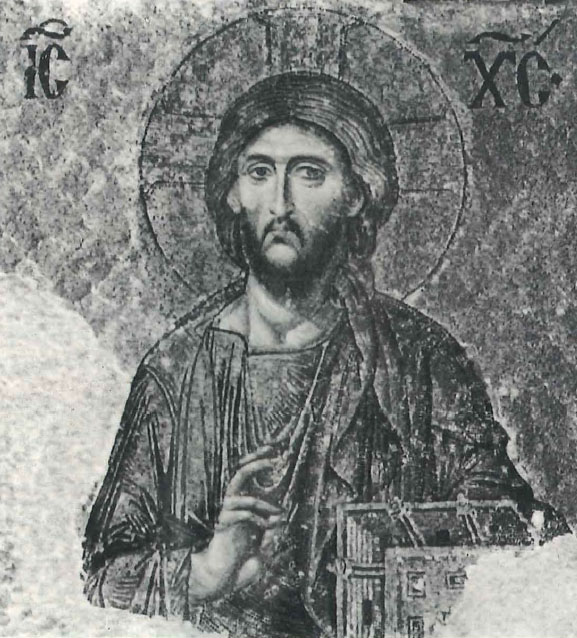

On the holy ground of Agia Sophia, the marbles of many colors, the alabasters, the jasper ornaments, the porphyries, the serpentine impose the feeling of being in a garden of purple flowers. The conqueror violated the mosaics and plastered over all human representation of God; only a few frescoes are to be seen, But the lower part of this prodigious church is panelled with marble inlays of heavenly variety and size. Fine jagged molds and large sculpted arches frame the marble inlays symmetrically positioned, iridescent in tone or veined concordantly. The enamel, this chromatic magic, spangles set with gold and colored stones to the highest degree of perfection, never attained elsewhere. Gold was here for the first time used to capture light so as to represent man in art, or heaven on earth.

Vladimir, Prince of Kiev, sent emissaries to the Muslim, the Jew, the Latin and the Greek to find out which was the appropriate religion to adopt. When they arrived to Constantinople, they were taken to Agia Sophia on a feast day. There, under the great dome studded with mosaic, with incense burning, in the blaze of candles and during the psalmody of “Holy, Holy, Holy is the Eternal”, the Boyars were bedazzled and believed the saying that “during the Greek Liturgy, the angels descend from heaven and celebrate liturgy with the priests.” Upon return, they declared to Vladimir: “We do not know whether we were in heaven or on earth, for on earth there is no such beauty. We do not know what to say, but one thing we do know: God is there, with man.”

In order to comprehend the spirit and the internal logic of Byzantine art, one has to keep in mind that Christ is the perfect God and the perfect Man unalloyed and unconfused”, as announced during the Council of Chalcedon in AD 451. It is this humanism regarded as sacred that has helped Byzantine art save the human figure from foundering as happened to the Monophysites, Islam and the barbaric West. In the rest of the Christian world, the human figure was either reduced to an ornamental sign or devored by the barbaric bestiary. Byzantium reinvented beauty already to be seen on the faces of the Orants of the Rotunda of Saint George in Thessaloniki, in the Nea Moni Monastery at Chios, or the Church of the Holy Savior in Chora in Constantinople.

Byzantium will continue to celebrate the mediations accomplished by Christ. Saint Maximus stated that “Christ unites man and woman, heaven and earth, the sensible and spiritual beings, and, ineffably the created and the uncreated nature.” He also showed that “celestial and earthly beings form one solemn ring.” It is this image of a conceived existence as a liturgic act, a cultural adoration and a “solemn ring” which Byzantium has realized on earth in the ecclesiastic rites and the palace ceremonies.

The Greek language and the Orthodox faith united the Empire as Byzantium was a second revival of Hellenism to which Christianity was grafted and which had a determining effect on western civilization. Byzantine Orthodoxy has given Hellenism its veritable historic dimension. Consider the Orthodox Fathers and their good old Greek confidence in nature, radiant in the canons of Saint Basil, the monastic legislator, in the gracious works of Gregory of Nyssa; or in the writings of Maximus the Confessor. The world is not this tenebrous prison that primitive Christianity vowed to apocalyptical destruction. The world is a Theophania, a ‘manifestation of God’ as Dionysios Aeropagitis said. In this universe where all existence is Theophania, every being is good, and evil is nothing but an unreal shadow. That is why the Greek Byzantines refused to portray demonic contortions that apocalyptic visions carved upon the portals of Northern European churches. No wonder the decadent painters of Byzantium used the paintings of Durer, Cranach and the illustrations in the Bible of Piscator to depict the horrific Apocalypse at the Convent of Dionysiou, or the churches of Jeroslav.

The expression of the ancient Philokalia was the fusion between man and God as a “drop of vinegar uniting with the waters of the oceans.”

“If,” as Eusebius defined it, “the Empire upon this earth is the reflection of celestial Heaven,” then no human can enter Agia Sophia without a chill that signifies the heavenly expression of the greatness of God in these premises, even for the staunchest non-believer.

Constantinople is not just Agia Sophia, but a continuous flow of churches and monuments that have painted, carved and built Hellenic history on this holy soil over the centuries.

The Byzantine churches have suffered but have survived. The Ecumenical Patriarchate is cocooned in Phanar, once a glittering Greek neighborhood. The Greeks had to leave and their houses were either left for time to reduce them to rubbles, or were occupied by Anatolians of another civilization. Houses standing since the 16th century fell prey to “modernization or cleaning up programs.”

Constantinople is still alive and kicking in the Vlachernes area (Karagumruk-Ayvansaray) with its numerous churches: in Philadelphion (Suleymaniye) under restoration; in Galata and Pera; in Mesochorion (Ortakoy) and Mega Revma (Arnautkoy) under restoration, with its lovely Sunday street bazaar, and where the Patriarch has his residence; lastly, in the aristocratic suburb of Bebeki. Everywhere else the city is quickly changing into a city of mixed, mainly Oriental, origin with a touch of Levantine flair one could experience in Beirut before it was destroyed.

The Municipality of Istanbul is actually restoring a good part of the city and the monuments the Greeks left behind, though the people that put the stones up are no longer there. The Heptapyrgion area and the Theodosian Walls near the Golden Gate, facing at the enemy from the West, are being completely restored with UNESCO funds, and look like the kitsch one can admire in Ben Hur or Spartacus.

The Prince’s Islands have not moved a stone for more than a couple of centuries, and Dr Sozen, the Mayor of Greater Istanbul, promised no one will dare touch a stone for as long as he is around. One should accredit Dr Sozen with the greatest restoration enterprise since Suleiman the Magnificent, without any exaggeration. Anyone who visited the city a few years ago would testify so.

But the city is not just Constantinople; it is also Istanbul. It is alive and, despite the soot that emanates from the burning of coal for heating purposes which covers and pollutes absolutely everything, it is an enjoyable city, especially for a Greek. I have had the pleasurable experience to be advised by many Turks I met that Greeks are more liked than any other visitor; I was treated with nobility you no longer encounter in many places. I was even invited to stay and live there. Dr Sozen is actually inviting all the Romii (Greeks with Turkish citizenship) to return to the city of their forefathers.

Food in Istanbul is good and service in tavernasis excellent. In some tavernas, people sit around the charcoal fire and watch the cook prepare their meat, just as described by Anna Comnena and Constantine Porphyrogennetus. Surely a togetherness Westerners have never experienced. The food has a style which gives it a sense of history as dishes have a mixture of Turkish, Farsi, Arabic and Greek names. This makes it difficult for any neurotic nationalist to trace its origin, if ever one could trace the origin of food. Good restaurants have, for generations, adopted a Byzantine and Levantine style that knows no structural border. Tavernas and restaurants are not as lively as the ones in Athens. By about eleven, things quiet down, and everyone is gone by midnight. Nightlife is poor and bars are rare.

Turkey is a man’s world. Women are not to be seen in the streets and, if seen, they have to wear a scarf or even more. One can notice many people from Eastern Europe selling their cheap items around the University area and the Covered Bazaar where things are more expensive than in other parts of the city as the tourist trade here, too, has pushed up prices while pushing down quality. Istanbul is a city of about 11 million people, three seas and two continents: a world you cannot discover in a few days.

Very few cities are as noble as Constantinople and as attractive as Istanbul. Where else can one encounter so many faces of history?

No wonder it is still called the Vasilevousa, the Queen City.