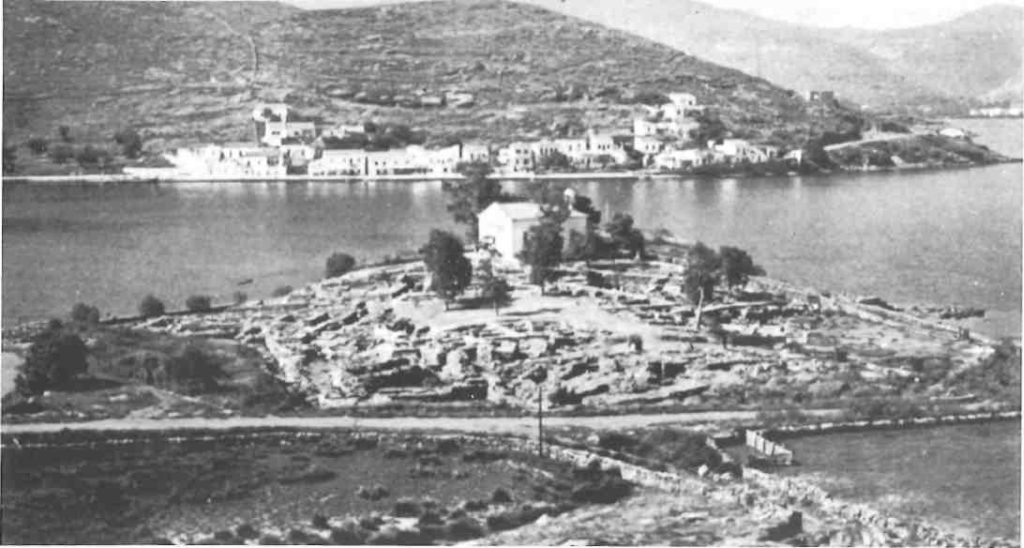

In the background is the tiny port of Vourkari.

Only 75 minutes, by Flying Dolphin, from noisy, overcrowded Athens, lies the island of Kea an oasis of space and tranquility so profound, it is almost tangible. Large, mountainous and sparsely inhabited (1700 inhabitants), wrapped in its own internal rhythm of life, it seems from a distance to rise sheer from the waves. But a closer look reveals hidden fertile valleys where cattle graze, sandy shores and blue limpid seas. Still scarcely touched by tourism, its bars and souvenir shops can be counted on ten fingers and no boutiques or kentra mar the charm of its traditional villages.

St Nicholas Bay, vast and indented, and one of the safest all-weather moorings in the Aegean, has attracted man since the beginning of time. Apart from remains and ruins littering its coastline, testaments in stone to continual habitation, it shelters three modern villages.

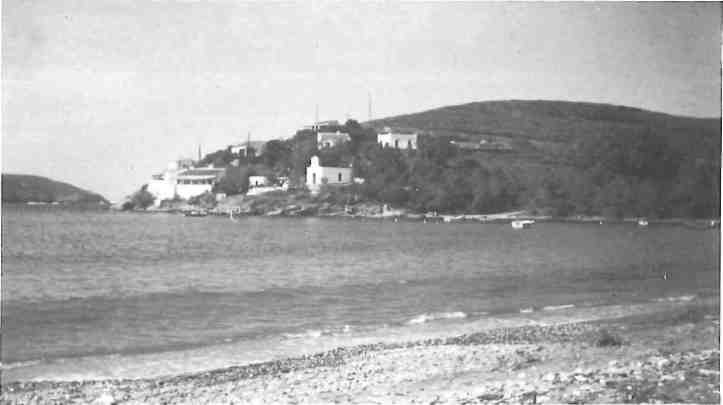

The main port of Korissia, known locally as Levadi, partly occupies the site of an ancient town of the same name, one of four which flourished during Archaic and Classical times. Whithin walking distance, Yialiskari clings to a steep rocky outcrop, its narrow beach fringed with tamarisk and cane. In the next inlet lies the tiny but rather sophisticated port of Vourkari, which is fast becoming fashionable with discerning yachtsmen.

This is a perfect spot to speculate, over lunch or a drink, on man’s transient glories, for directly opposite on the small peninsula of Aghia Eirini, archaeologists (American School) have brought to light the remains of an important Bronze Age trading town. Its lanes, houses and fortifications, some of which now lie under water, and all built from local pale green schist, are easily discernable even to the layman’s eye. Also in view are the deserted buildings of the coaling station which, in the great days of steam, serviced ships bound for Constantinople and beyond. Time and progress have turned them, too, into ruins.

Some six kilometres inland, Ioulis, the main village of the island (Hora) which occupies the site of an ancient city of the same name, spills 300 metres in a tumble of sugar-white, red-roofed houses, down the stepped hillside. It is linked to the port by a bus, which is infrequent and runs to an almost ficticious timetable, or by one of the island’s four taxis. They will take you only as far as the town gate. No cars can manoeuvre the steep, paved lanes which prove a litmus test for fitness, while carrying your luggage (make it light!) up to one of the two hotels becomes a feat of endurance.

Should you be feeling particularly energetic, you pay your first visit to the Kastro, what is left of a 14th-century Frankish castle where the ancient Acropolis once stood and from where today there are literally breathtaking, aerial view across the blue expanse of sea to the Attic coast.

The Archaeological Museum in the main part of the town, is also well worth a visit (admission free). The top floor houses the interesting Bronze Age finds, some of them reflecting Minoan influence, from Aghia Eirini. Below, are the antiquities from the island’s four ancient cities, which span the Archaic and Roman eras. Each exhibit is well labelled in both Greek and English but unfortunately there are no postcards or books on sale and the taking of photographs is forbidden.

Nearby on the pocket-sized main square, dominated by the neoclassical town hall, there are a couple of tavernas. And, in case you thought you had left reality behind, enlarged photographs of Mitsotakis and Papandreou glower across at each other from their respective political offices. The main lane, which winds its way through the houses, continues on outside the town where it passes an enormous lion. Carved out of a single block of green schist by an unknown Ionian sculptor around 600 BC, it is said to have frightened off evil nymphs which, mythology has it, once plagued the inhabitants.

Like its modern namesake, ancient loulis thrived on husbandry and agriculture introduced, they say by the Thessalian, Aristaeos, who arrived on the island with a band of Arcadians bringing rain with him during a drought and was thereafter worshipped as a god. Gods aside, the city, for some reason, produced a truly remarkable number of doctors, philosophers and sophists, the most remarkable being Prodicus who is less well-known now than his pupils Socrates, Euripides, Thucydides and Xenophon.

It is perhaps Kea’s poets Simonides and Bacchylides who have the greatest claim to fame. The former became what was almost a poet laureate of Athens, writing elegies, epigrams or dirges as the occasion required around the time of the first Persian invasion. It was he who penned the famous inscription, in suitably Laconic style, to honor the Spartans who died holding the pass at Thermopylae against the advancing Persian army. Little was known of Bacchylides works except from fragments and by repute until surviving manuscript copies, now in the British Museum, were discovered very much later in Egypt.

The of the most fertile Cyclades, in antiquity, Kea was covered by a dense forest of mainly oak trees, which sheltered boar, wolf and bear. Kean bear meat, a 13th-century Archbishop of Athens remarked in astonishment, was regarded as a delicacy by the unsophisticated Franks who then occupied Greece. Part of the ancient woodland survives in the southern half of the island, where, in an area of particular beauty, slumber the some-what inaccessible remains of Karthaia, the oldest and wealthiest city of the ancient tetrapolis. Like the three other independent towns, it issued its own coins at a time when the island flourished on trade and the export of miltos (enamel), a red-ochre mineral which was much sought-after for use in medicine and red paint. From the remains of three large Doric buildings, which dominate the isolated sandy beaches below, there are stunning views over the open sea to the west.

It was probably built on the site of an earlier settlement, for Kea at the dawn of history, like the other Cycladic islands, attracted trading Carians, Pelasgians and Phoenicians to its shores and has been known by many names; Euxantis, Kiano, Merope and then Hydroussa because of its plentiful water supply. Oral history passed on the story that the island was then named after a hero called Keos who arrived there in the 12th century BC at the head of a band of Locrians from Naupactos on the Gulf of Corinth. Just what he was doing so far from home is unknown, but at Karthaia a marble inscription refers to the city’s connection with Naupactos, so oral history may be right. Later, in Christian times when Venice ruled the seas, it was latinized to Cea or Zea which the locals pronounced Tzia, still its popular name today.

The Keans in history were known for their sobriety, politeness, and independent nature and differed in many ways from their Cycladic neighbors. They were, for example, the only islanders to fight alongside the Greeks against the Persians, sending two fully equipped triremes to the battle of Salamis. They, too, had their own strange customs one of them being the Kean Law which prevailed until the coming of Christianity. This was an early form of euthanasia, accepted by all citizens, who when they reached the age of 60 (some sources say 70) drank hemlock -the same poisonous herb which Socrates drank when he was condemned to death in Athens – so that the youth of the island could live better.

Even today the Keans are polite but not gushingly so, and view tourism, which is still in the embryonic stage, as a doubtful blessing to be welcomed cautiously. The island has few hotels or even rooms to let and those are patronized mainly by Greeks from Athens. The only holiday complex is Kea Beach, complete with thatched windmills, which is on the coast at idyllic Koundouros Bay. It is self-contained in that it has its own tennis courts, swimming pool, taverna and entertainment.

North of Koundouros Bay lies another almost as beautiful, at Pisses, the site of the fourth ancient city, Poiessa, of which there are few remains. Today there is only a scattering of houses and a superb sandy beach, where for some reason the water always seems warmer than at other parts of the island. Just a little to the north at Aghia Marina is a square Hellenic tower which is the best surviving example of its kind in the Cyclades.

Kea holds few thrills for tourists hell-bent on a swinging holiday of the booze, boobs and bars variety, though a disco does materialize at both Korissia and Ioulis in summer. It is rather what the islands must have been like some 20 years ago, before the advent of mass tourism in the Aegean, when archaeological sites were not fenced off, the roads were empty, the beaches pristine and the sea unpolluted.