A long with the hum of cicadas in the pine trees, the clinking of ouzo glasses and the lapping of waves, the rattle of dice and the clatter of plastic counters on wood must rank amongst the most evocatively Greek of sounds. With the first inkling of summer sun comes that imperious call of trapezakia exo! (out with the little tables!), and makeshift open-air mini-arenas spring up on Athens street corners, in garage forecourts, beneath the accommodating branches of village plane trees. All thought of work is banished as the two players give themselves over entirely to the game and the friendly banter which is so much a part of it: Backgammon in English, meaning ‘back game’, because the pieces go back to the beginning again or re-enter; Tritrak in French, after the noise made by the counters; Brettspiel in German, meaning wooden-board game; and in Greek, Tavli, from the Roman and Byzantine name tabula, meaning table or board.

The precursors of modern tavli, which is the oldest of all board and dice games, date from as early as 3000 BC. The oldest gaming boards known were found in the royal tombs of Ur in Mesopotamia, and although no account survives of how the game was played, there appear to be striking similarities to backgammon. Each player had seven marked pieces whose moves were controlled by six pyramidal dice: three white and three lapis lazuli. Later, the ancient Egyptians used boards developed from the type found in Ur which bears an even closer resemblance to our modern game.

Several were found in tombs of about 1580 BC which were actually constructed as a box, containing the dice and pieces inside, and on the underside of the box some bore the marking of a game known by archaeologists as the Game of Thirty Squares. At this stage, the dice comprised either two knuckle bones (the ankle bones of a sheep) marked on four sides, or so-called ‘long dice’, but by the time the game was adapted by the Romans, these had been replaced by the cubic variety. The Roman game was known as Ludus Duodecim Scriptorum (twelve-lined game) and was almost identical with modern tavli.

Meanwhile, cubic dice, or kyvoi, had been known in Greece since Homeric times: legend has it that the great inventor Palamedes first fashioned the dice as a means for the Achaeans to while away their time at the foot of the Trojan walls between battles, very nearly causing them to come unstuck on one unfortunate occasion – the Trojans launched a surprise attack when they were deeply absorbed in their game!

In the first century AD, Ludus Duodecim Scriptorum gave way to Tabula, a variant with only two rows of marked off spaces, which developed in turn into ‘tables’, or tavli, more or less in the form we know it today. During the Middle Ages, it flourished in the bazaars and inns of Persia and the Byzantine Empire, the game of travellers and traders. Like other Persian games, such as polo, backgammon was brought to western Europe by the crusaders, and was at first a game of the royal courts and the gentry, gaining in popularity after the Renaissance.

In Greece and the Balkans, the spread of tavli coincided with the development of the kafeneion as the main cultural centre of every town during the 16th century, and in the two following centuries further urbanization promoted the spread still more. In the 19th century, the kafeneion became a part of village life too, bringing with it, of course, the game of tavli.

Part of the attraction of tavli to the 20th-century player surely lies in its portability and the simplicity of the required apparatus: two dice (traditionally, and perhaps mainly for reasons of superstition, a shaker is not used in the Greek game, as it precludes that all-important ‘feel’ of the dice. The ability to ‘fix’ the dice is a rare, though much revered, skill), 30 pessous (counters or ‘men’), usually black and white and made of wood or plastic, and a hinged wooden board (serious Greek players turn their noses up at the small modern bound leather variety found further west, as it lacks the necessary acoustic qualities of the traditional Greek board!).

The normal size is 40 cm long by 20 cm broad and 10 cm deep, and each compartment of the board has two ‘tables’ consisting of six chevrons. In the English game, each player calls one side of the board his ‘inner table’, and

the other his ‘outer table’. In recent years, a so-called ‘doubling cube’, having the numbers 2, 4, 8, 16, 32 and 64 on the six sides, representing gambling stakes, has given a boost to the popularity of backgammon in America and western Europe, but in Greece the game remains primarily a battle of wits, in both senses of the word, the ritual teasing of one’s opponent being just as much an essential element of the game as those of risk and skill, which are so nicely balanced in tavli. “You rely completely on the luck of the dice,” they jibe “while I have to look to my own skill,” or, if the opponent has inadvertently taken the dice to start the next game, when he has lost the previous one and therefore is not entitled to, “Come on! Give the dice to the mastora (expert)!”

Another major difference between Greek tavli and international backgammon is that in Greece at least five distinct variations of the game are played as opposed to just one. The three most common – portes, plakoto and fevga ~ are normally played in the same order in rotation, and the first player to achieve seven victories is the winner of a round. To begin the game, each player rolls one dice (which must land within the box to count), and the highest throw starts. In subsequent games, the winner of the previous game always plays first.

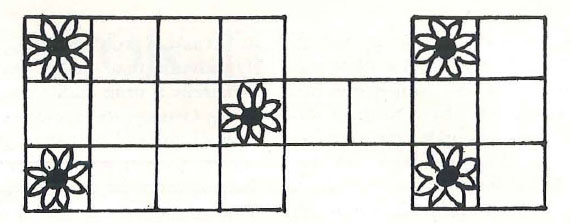

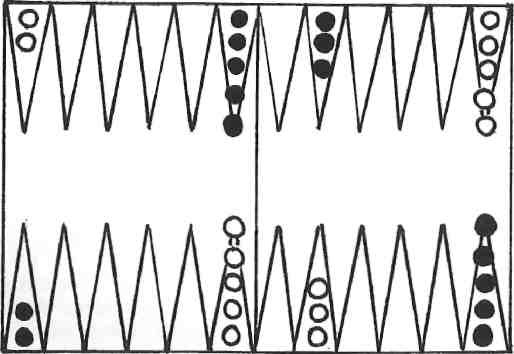

Portes, or ‘doors’, the first game in the Greek sequence, is also the internationally-known game, featured in a special weekly column of the New York Times and played in international tournaments. At the start of the game, also sometimes known as ktipito (literally hit) in Greek, each player arranges his counters on the board in a specific pattern. As in plakoto and fevga, the basic object of the game is to move one’s counters all the way round the board, and then to ‘bear them off, or remove them from the board, the first player to do so being the winner. In portes, the starting point, or mana (literally mother), of each player is directly opposite that of his opponent, and while one player moves his men in a clockwise direction, the other progresses in an anticlockwise direction. If a single counter is left on a point (known in English as a blot), an opponent’s counter may land on top of it (thus hitting a blot) and the counter is withdrawn temporarily from the game, being placed on the central bar until it re-enters the game from its mana compartment. In the event of the re-entry of the withdrawn counter being blocked by opponent’s men, the first player must wait until his counter comes back into the game before making any other moves. As in the other games, if one player manages to move all his counters round to the compartment from which his opponent began and bear them off before his opponent has picked any up, he wins a double game, or mars, as it is called in Greece, and scores two points.

Plakoto, the second game in the sequence, is said to involve more luck than the other two. The mana and the direction of play are the same as in portes, but at the beginning of the game each player places all 15 of his counters on his mana point. In addition, when a counter lands on a chevron occupied by a single counter of his opponent, it ‘sits’ on top of it, preventing it from moving. As in portes, if a player has two or more men on one point, a ‘door’ is formed and his opponent cannot land on that square but is obliged to jump over it. If a player has the good fortune to land on top of one of his opponent’s counters in the chevron next to his mana (the paramana), he is almost certain to win, while landing on the mana itself virtually assures him of a double game, or mars.

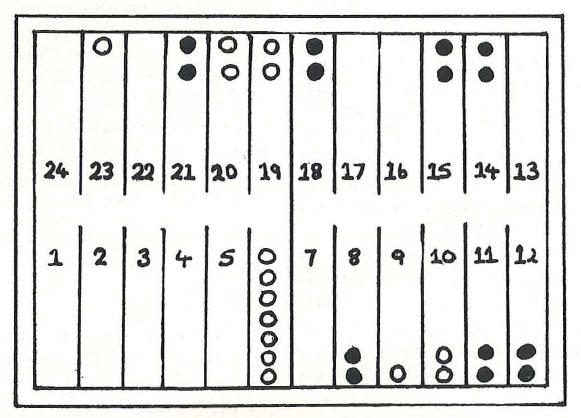

Although it may appear very simple at first, Fevga (sometimes called bouldezim, a Turkish word meaning a kind of tax collector), the final game in the sequence, is considered by experts to require the most skill. At the beginning of this game, each player positions his counters in his bottom left-hand corner, diagonally opposite those of his opponent, and he moves his counters in an anticlockwise direction, bearing off from the compartment opposite his mana. Before he can move any other counters, each player must have moved his first counter to the compartment from which his opponent started. In this game, a chevron may only be occupied by one man at a time: counters do not land on top of other counters, neither are they removed from the board. The object of the game is to have one’s counters spread out around the board in such a way as to facilitate one’s own passage around the board, while making it as difficult as possible for one’s opponent. A player must not block the first six spaces in front of his opponent’s mana, though he may block continuously anywhere else on the board, but he must not create a situation of stalemate: he must always leave his opponent some space to play.

Other games, played less frequently, include gioul, a variation on fevga, and to evraiko (the Jewish game), a simple game, often the first one taught by grandfathers to their grandchildren. For tavli, the most ancient of board games, is, fittingly, a special tradition in Greece whose secrets are passed down from generation to generation.