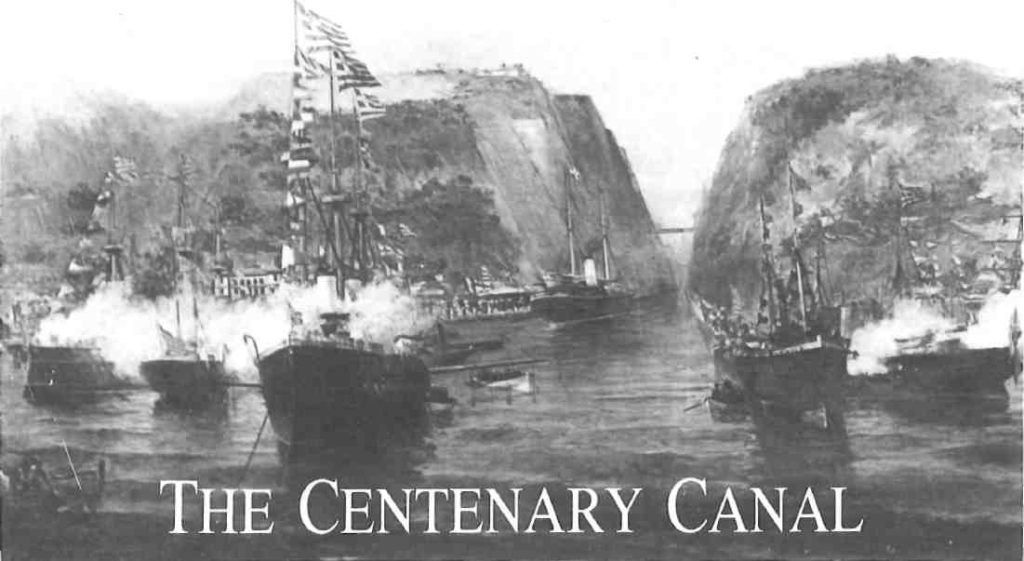

The long-awaited opening of the Corinth Canal produced a heady, jubilant atmosphere of pride and relief. July 25, 1893 by the old calendar then in use (August 6) was a day of intense national pride and the natural harbor of Kalamaki was en fete. Newspapers and journals of the day describe the scene as bands played, flags and bunting fluttered in the breeze and banners proclaimed long life to the Greek nation, the unification of the people, and the royal family.

Flag-bedecked warships, French, Russian and British as well as Greek, rode gently at anchor in the bay while small boats and tenders criss-crossed back and forth. The steamship his had already arrived from Piraeus bringing government officials and members of parliament. It was followed closely by the Thessalia carrying General Stephan Turr, the Hungarian engineer who had designed and constructed the canal. Other ships brought hundreds of excited Athenians, elegantly dressed for the great occasion, to swell the awaiting crowds of spectators, sailors and sol· diers of the local Corinthian Infantry brilliant in their dress uniforms. All waited in growing suspense for the arrival of the official flotilla.

At nine sharp (the meticulous arrangements were carried out with precision) the Hellas with the Greek royal family onboard, steamed out of Piraeus on its three-hour voyage. Flanked by the Russian and French flagships and followed by the Psara and the King George, its departure was marked by a multi-gun salute and the rapturous cheers of the flag-waving crowds which had lined the quays since early morning anxious to participate in some way in the historic occasion.

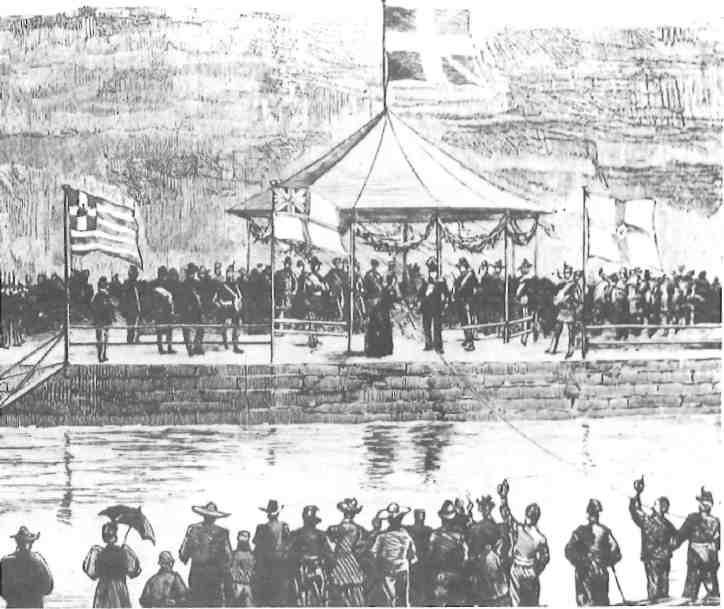

Punctually at noon, rousing cheers and a cannonade signalled the flotilla’s arrival at Kalamaki. After disembarking quickly each member of the royal party, which included the king’s father-in-law, the exuberant Russian Grand Duke Constantine, was greeted personally by General Turr, the hero and host of the day. When everyone was seated, the general began the ceremony by handing a small silver spade to King George I of the Hellenes, inviting him to place three symbolic spadefuls of earth into a small elegant wheelbarrow with silver handgrips. This was in turn passed to Prime Minister Sotirios Sotiropoulos who emptied the earth into a pool of water in which had been placed a marble block commemorating the official ceremony on 12 April 1882 when work had started on the canal. The intervening eleven years had been fraught with difficulties, bankruptcy and broken dreams.

It was therefore with immense satisfaction that the popular Queen Olga activated the electric current which dynamited forty specially-made cuttings and blasted turf and rock spectacularly into the air to the cacophony of the almost hysterical cheering of the crowds and thunderous band music. With emotion and pride the canal was declared ‘open’ and its future blessed by the church dignitaries present-General Turr entertained the official party to lunch during which enthusiastic speeches were made in French and Greek and a congratulary telegram was read from the great French engineer Ferdinand de Lesseps who had successfully constructed the Suez Canal.

At four o’clock the royal flottila set sail again for Piraeus. The day had been a magnificent and unqualified success. The millennia-old dream to unite the Corinthian and Saronic Gulfs had finally become a reality. And the ancient ‘curse’ of the sea god Poseidon who, the locals tenaciously believed, abhorred the idea of mingling the gulf waters, had at last been laid to rest.

Indecision and failure had dogged all previous plans and attempts to split the Isthmus of Corinth since the notion was first proposed around 600 BC. Periander, tyrant of Corinth, had been eager to increase his prospects for a share of the lucrative Nile trade. But apparently it was he who settled for a paved slipway known as the diolkos across which ships and merchandise were hauled on a train-like wagon from one gulf to another.

Later leaders from Alexander the Great to Julius Caesar had toyed with the idea of constructing a canal and the Roman Emperor Gaius Caligula got as far as surveying the isthmus but his Egyptian engineers announced that, as the level of the water in the Corinthian Gulf was higher than that of the Saronic, its waters would flood Aegina and the surrounding shoreline.

It was Nero in 67 AD, using six thousands Israeli slaves sent to him by Vespasian after the ‘pacification’ of Judea, who made the only serious attempt. But despite his theatrical inauguration ceremony, which the unstable emperor believed emulated those of Periclean Greece, work stopped after three months. A rising in Gaul was blamed but, in all probability, his engineers had run into difficulties with the heavily-faulted chalk dunes in the centre of the isthmus which so bedevilled nineteenth century attempts. (Nero’s cuttings were examined by the French School of Archaeology in 1884 before being destroyed by work on the existing canal.)

Hadrian and, much later, the Venetians no more than contemplated continuing the work. But in 1830 Greece’s first president, the progressive John Capodistria, enthusiastically commissioned French engineers to draw up plans. The cost proved prohibitive and the penniless, fledging nation could not raise the required loan on the open market.

The completion of the Suez Canal in 1869 again gave rise to canal fever. One of its ardent supporters was the philhellene Turr, a colorful and well-known figure in Paris. He had been connected with the original plans for the Panama Canal. During an international geographical congress in Vienna he proposed, or perhaps seconded, a resolution to construct a canal at the Isthmus of Corinth. The following year, in May 1881, he succeeded in winning a land concession from the Greek government and formed a company based in Paris, Societe Internationale du Canal Maritime de Corinthe.

Its objective was to “shorten the ocean route from the Western Mediterranean and Adriatic Gulf to seaports of Eastern Greece, Turkey, Asia Minor and the Black Sea” and avoid the “dangers of Cape Matapan and the Malea Head, places known to the Greeks as slayers of men.”

With a surge of confident optimism it was further proclaimed that as the work was straightforward, it would be completed in four years and its profits would be “even greater than those of the Suez Canal”. Shares yielding an annual interest of six percent sold at 500 francs each and the scheme was so well received that the required capital was subscribed “five times over.”

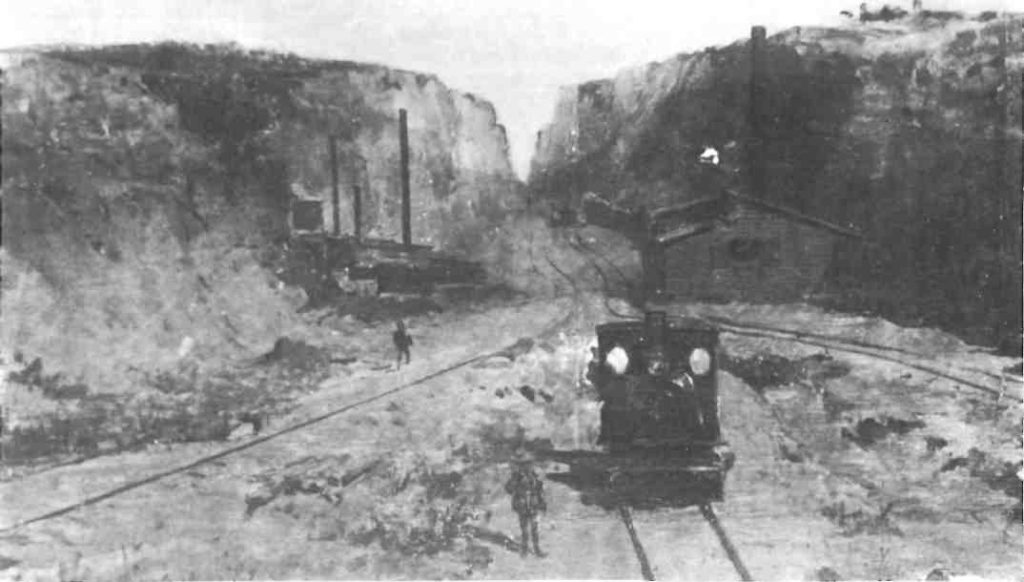

With hopes running high, construction work got underway in April 1882 after an official ceremony attended by the Greek royal family, state officials and VIPs. At first all went according to schedule until the engineers reached the limestone and chalk dunes which rose in the centre of the isthmus to a height of some 100 metres. Being both heavily faulted and rich in flints and oyster shells, these caused serious problems.

Various methods of excavation were tried but after five years, with the project still unfinished, the ugly realization came that the subscribed capital would not be enough.

In spring 1888 amid growing rumor and disquiet, the capital finally ran out and feverish efforts were made to raise a further sum of 3.5 million francs. With a desperate show of normality, to allay panic, work continued piece¬meal. But never-ending excuses were published in the press to justify stoppages: the bitterly cold winter of 1888/9, two earthquakes in January 1989, the financial crisis in Paris in March, when interest payment was deferred. Patience, too, finally ran out. One of the main sub-contracters, smelling several large rats, demanded one million francs in payment and occupied the works when he didn’t get it. His action precipitated a financial uproar of international proportions.

In the end the Civil Tribunal of Paris took the matter in hand and adjudicated for the contending parties. In February 1890 the company came under the hammer and an official liquidator was appointed.

Out of this chaotic and bitter fai¬lure, Greek banker and financier Andreas Syngros married patriotism to business and bought what was left of Tiirr’s company, creating the ‘Corinth Canal Company’ with a capital of 200,000 pounds and the authority to raise a further 15 million pounds on the open market. Construction began again.

There was some serious nail-biting when news came of the scandal surrounding the collapse of the Panama Scheme and the loss of 60 million pounds in the mosquito-ridden swamps of Panama. Relief was therefore all the more heartfelt when the construction of the protective harbors at each end of the canal signalled that the work at Corinth had finally been brought to a successful conclusion.

Sadly, the canal did not bring the promised prosperity to the surrounding area. Many of the main shipping lines of the time, such as Austrian Lloyd, did not use it. And Britain’s large merchant fleet, refueling at Gibraltar, Malta and various Cycladic islands, had no use for it. By 1906 it was taken over by the National Bank of Greece which created a new, later nationalized, Corinth Canal Co. Ltd (AEDIK) which still runs it today.

Although the canal is straight, negotiating the six kilometres is not without its problems as there is a fast running current of two to three knots, and larger ships require a pilot. But for those sailing between its precipitous cliffs (only 25 metres apart), the passage through the historic canal is an exhilarating and unforgettable experience.

It is used by all kinds of vessels from cruise and merchant ships to yachts -13,000 vessels from 61 countries passed through it last year bringing in one billion drachmas in revenue. The company’s President Thomas Thomaidis has strenuously denied rumors of privatization and earlier in the year announced plans for the centenary celebrations.

Between 20-25 July there will be performances of dance, theatre and music at Isthmia and, at the end of September, representatives from all the countries using the canal will be invited to attend a Pan-Mediterranean conference there on ‘Shipping and the Economy.’ This will tackle, among other issues, maritime trade and tourism.

Plans have already been drawn for a large classical amphitheatre capable of seating 2500 people. Performances will take place on a floating stage. Phaidon Kyriakis, the company’s managing director, was hopeful that it would be finished by next summer and that work would also get underway on the planned marina at Isthmia. He stressed that only Greek contractors would work on these projects. There are also plans for a small museum and library.

Brussels has already recognized the canal’s ‘historic value’ and AEDIK is hoping to receive partial funding from the EC Delors II package. This will be used to replace holding parapets along the cliff tops of the canal to block rock-falls, and also to deepen the canal by two and a half metres.

All told, in this its centenary or ‘golden’ year, as the company is calling it, the future looks bright for the Corinth Canal.