Like a stone ship, the massive castle of Methone lies perpetually grounded on the reef from which it receives its name, ‘Mothon Rock’, at the south-westernmost tip of the Peloponnese. It gives the impression of riding low in the water, heavy with the weight not only of its walls, but, it seems, of its history burdened with cruelty, greed and slavery.

For all its outstanding natural beauty, Methone has been inhabited from long before recorded history because of its strategic location. In 1943, during the Occupation, the military blew up a section of the exterior curtain wall which revealed construction from all periods of Methone’s history: ancient, medieval and modern.

As Pedasos, it was one of the seven cities that Agamemnon promised to Achilles as a dowry on his marriage to Iphigenia. It was a deceit, of course. The bride-to-be was sacrificed for expediency’s sake. So from the start Pedasos/Methone’s history was military and melancholy.

A millennium and a half later, Belisarius moored his Byzantine fleet here in AD 533 setting out to reconquer Italy and the West for the Empire. Its success was short-lived. Arab conquests followed, the Saracens took to the sea, and for centuries afterwards Methone was above all dreaded as the haunt of corsairs.

With the little, cave-indented islands of Sapienza, Schiza and Aghia Mariani lying just across the straits of Methone, pirates were in no want of cover as they waited to pounce on the merchant vessels travelling the lucrative Byzantine trade routes.

Methone’s ‘piratical industry’ was encouraged by the Emperor John II Comnenus in an attempt to inhibit what he perceived, under the ambiguous term of ‘Crusade’, as a potentially dangerous build-up of Western soldiers and commercial interference in and around Byzantine lands. As the Crusaders passed through his territory they violated Imperial permission and looted and plundered the countryside as pirates did the seas.

The expedient accord his father Alexius I had concluded with the Venetians in 1082 had given them trading privileges which far exceeded those of his own Byzantine merchants. When he tried to extract himself from that rankling, 40-year-old treaty, the Venetians retaliated by attacking Byzantine strongholds along the trade lanes. Methone was besieged, forcing John II to ratify a new, equally disadvantageous trade agreement in 1126.

The Venetians left Methone desolate. Its inhabitants were carried off into slavery, its fortification destroyed, and the city within its walls was so laid waste that its ruins were noted when a storm forced a crusading knight to seek shelter there in the early winter of 1205.

It was a fateful tempest that brought Geoffrey de Villehardouin to Methone. He had joined the Fourth Crusade but split with the main group when he discovered that the mendacious and greedy Republic of Venice was diverting the expedition against the infidel towards the more glittering prize of Byzantium.

His uncle and namesake, the chronicler Villehardouin, wrote about his nephew and his connection with Methone, which he called Modon, in his 13th-century Conqueste de Constantinople. ‘The injury sustained by his ship compelled him to winter in the country which,coming to the ears of a Greek who was a powerful lord of the country, he sought him, and having treated him with much distinction; addressed him in these terms: “Fair sir, the Franks have subdued the city of Constantinople and have made one of themselves emperor. If you are inclined to bear me company, I will observe good faith towards you, and we will possess ourselves of much of the territory in this neighborhood. And so it came about. Though obviously biased in favor of his nephew, the chronicler tells truthfully how the Franks became involved in the Morea. Methane’s winter storm was the instrument by which Geoffrey discovered the wealth of the land and the vulnerability of its arms.

This “powerful lord of the country” was John Cantacuzene. Connected with the imperial family of Angelus, rivals and relatives of the Comneni, he well understood that his country was leaderless, and clearly intended to enlist the mercenary aid of the Franks who had, quite literally, landed on his doorstep. He thereby stood a chance of retaining a good portion of the Peloponnese for himself and his fellow Greeks. It was a gamble that he might have won had he not died the following year.

His son, Michael, lacked his father’s diplomatic skills, and when he saw that the Franks intended to carve a principality for themselves out of his ·land, he broke his father’s alliance and called his men to arms. But these provincial Byzantines proved incapable of taking on the Latin warriors, and with within four years, Geoffrey de Villehardouin had become Prince of the Morea.

Ironically, however, he was unable to take possession of the spot where he had landed to stake out his considerable realm. Al,ways with their eyes on long term, the Venetians, on the eve of the sack of Constantinople in 1204, acquired this salient spot controlling the sea lanes to the East.

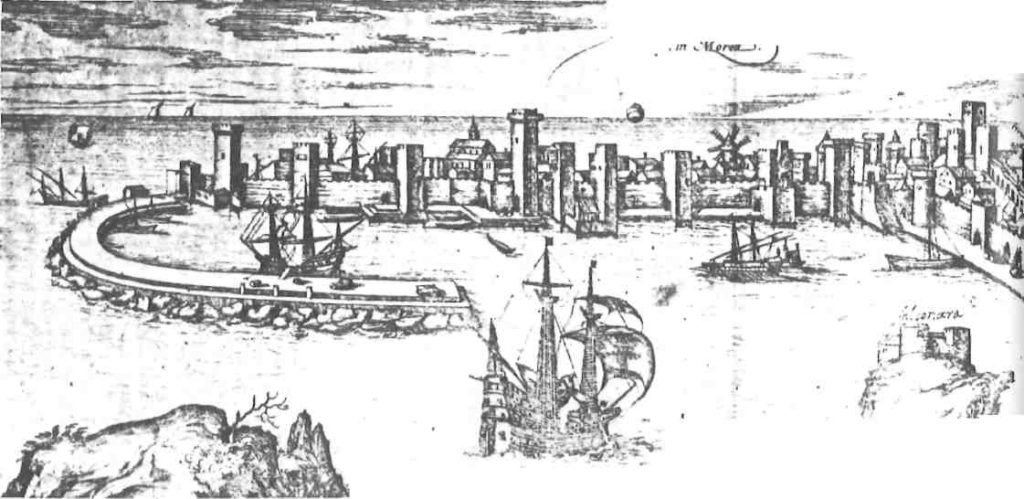

The Venetians held Methone for nearly three centuries. During this period they raised the vast fortifications on the ruins of ancient ones, transforming Methone into the largest fortress in the Peloponnese. Her population of colonists and native Greeks lived in peace and enjoyed the trading advantages of being, it was said, “half way to every land and sea.”

But in the 15th century the Serene Republic’s strg~tagem of playing rivals off one another contributed to her own downfall. The Franks of the Morea and the Orthodox Despots of Mystra were small-time players in the field in cornparison cornparison with the hordes of Ottoman Turks collecting for their -descent on the Morea, and Franks, Despots and Venetians were vanquished severally.

In 1500, Sultan Bayazid II, with an army of 100,000 men .and 500 siege guns, blockaded Methone and her garrison of 7000 for a period of one month. In a freakish climax to the assault, the Venetian garrison let down its guard in order to welcome four relief ships which had managed, with brilliant manoeuvring, to break through the Turkish blockade. In that moment of diversion the Venetians lost the battle, the castle and, most of them, their lives, for the amazed Janissaries seized the chance and swarmed over the momentarily unmanned castle walls. Taking their last stand on the little reef at the most southern point of the peninsula, the Venetians were cut down. Those few who managed to escape by sea to Zakynthos looked back in horror at the catastrophe and the smoke of the conflagration filled the sky.

The Turks held the castle for 185 years during which time its most celebrated prisoner was Cervantes, and many believe that the story of the captive in Don Quixote was derived from the time that Cervantes, missing an arm lost at the Battle of Lepanto, was incarcerated here.

In June, 1685, the Venetians recaptured Methone under Morosini, who directed the destruction of the Parthenon two years later. During the assault, the women and children were shut up in the Turkish-built fort of Bourdzi in order that their cries of anguish could not be heard by the attackers. Thirty years later, in 1715, the pendulum swung back and the Venetians left Methone for the last time.

In 1825 the ruthless Ibrahim Pasha, son of Egyptian ruler Mohamet Ali, captured Methone during the Greek War of Independence and used it as his headquarters for three years. It was from here that he waged war not only against the inhabitants of the Peloponnese, but its vegetation, uprooting and destroying all the trees in the vicinity. Shortly thereafter, with a fleet of small vessels concealed behind the island of Sapienza, Miaoulis set his fireships into the harbor by night and wreacked havoc on Ibrahim’s Turko-Egyptian fleet. Twenty-five warships and transports were destroyed along with buildings and sections of the castle walls.

After the final destruction of the Turkish-Egyptian fleet by the Allies at nearby Navarino in 1828, the French occupying force under General Nicholas-Joseph Maison found the buildings inside the castle in ruins. Removing all vestiges of the town from within the enceinte, he had his men build a new town outside the walls.

Today, the town of Methone is an interesting and pleasant interlude for tourists who have had enough of the Peloponnese’s graceful columns. However, the massive walls set above the one-time moat do not calm the senses. Here remains an unrest in the soul.

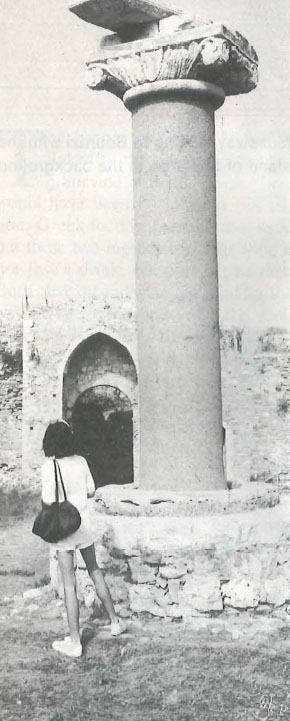

Bembo monument (1494) in the castle

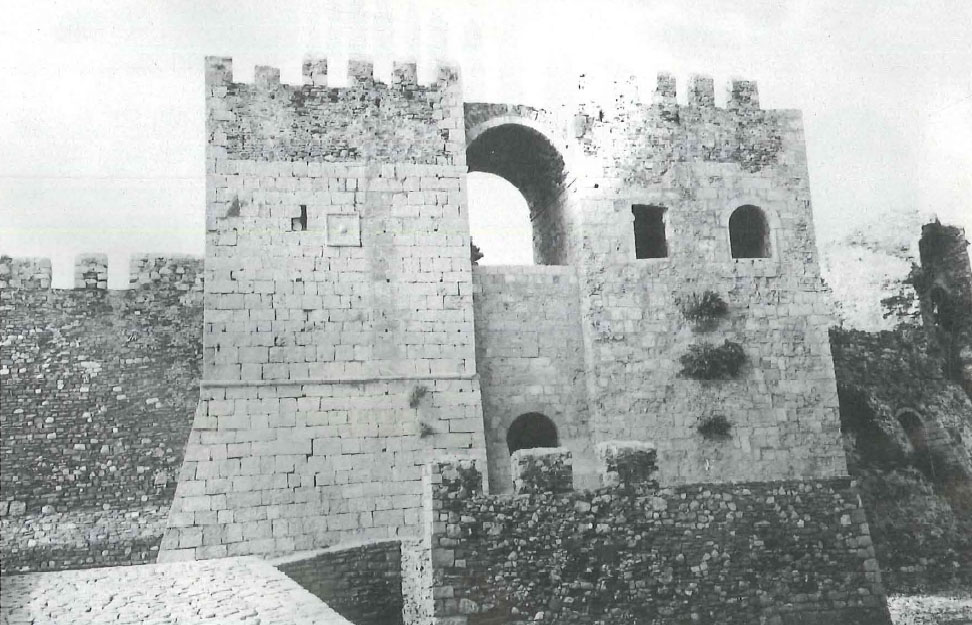

enclosure with the inner entrance gate

beyond

Corridor connecting the first two entrance gates

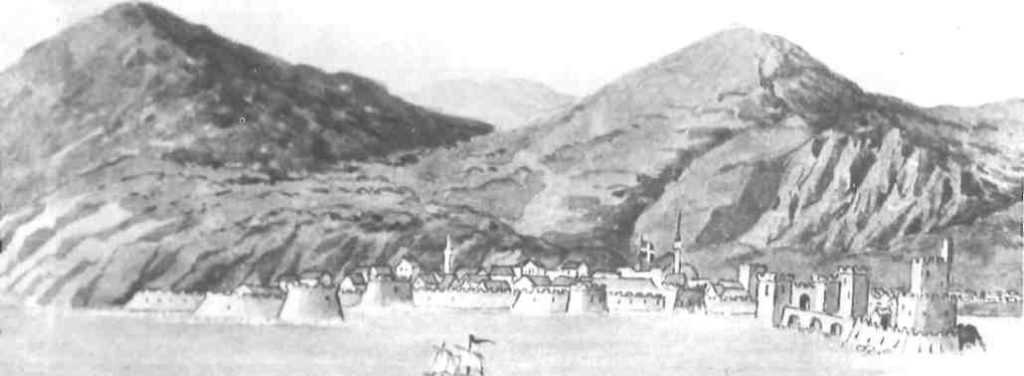

View south from castle enclosure towards Bourdzi

Immediately to the right of the gate at the end of the 14-arched cobbled bridge, is a path leading passed a bastion to the north side of the castle. It was along here that the Turks poured over the walls when the Venetians fatally turned their backs to welcome the relieving ships. Left, at the entrance gate, a long, spacious, high-walled corridor with dark chambers opening off it, leads to a second gate, and this to a third, which finally opens out into the enormous expanse of the outer castle enclosure.

At several locations on the walls can be found the coats-of-arms and the Winged Lion of St Mark. Two fine examples are set into the wall that divides the outer from the inner enclosure. To the west, the sea licks the castle wall and windsurfers in these gusty straits mock the graves of the medieval galleys that lie below the shoal-filled waters. It is along here, too, where the wall, destroyed during World War II, revealed thousands years of human habitation.

Only two buildings still stand inside the castle walls – the ruins of a church and Turkish baths. Attention, however, is drawn to the gleaming south gate framing the octagonal fortress of Bourdzi, one of the most photographed medieval sights in Greece.

Why is it then, right here, in the center of this picture postcard, on entering the octagonal keep, that one is chilled to the bone? Not because of the change in temperature, which is welcoming after the burning sun. May not it be that – just out of earshot, just above the click of the cameras – we imagine to hear the cries of women and children and the smell of the dark, dreaded fear that their cries fed on, still incarcerated here in history?

Let us zigzag our way down the eastern path, passed the harbor gate, toward the exit. Let’s admit that we have had enough of Castle Methone. It was hot. It was tiring. Here ahead are the welcoming houses with red-tiled roofs that General Maison built across the moat. A little further on, where the swimming is fun, we can sit under a tree and sip an iced ‘Nes’ and eat baklava. Listening to the delightful sound of today’s happy, carefree children, we can look back safely at those walls which are there for our tourist enjoyment. Aren’t they? Those walls at whose feet the poppies and the pimpernels dance – almost the color of blood. And the laughter of children – almost like cries.

There still hovers over Methone an uneasiness. Nothing here of the tranquillity felt up north at Olympia and Bassae, none of the sense of romance – whether real or not – which invests the Frankish castles of Chlemoutsi and Karytaina. Here, built into these very walls, is the enigma of the Greek experience: a blight on an ancient land; a blemish that marks the face of beauty.