Renowned for their Minoan discoveries at Archanes near Knossos, Yiannis Sakellarakis and Efi Sapouna-Sakellaraki will soon lead a three-week excavation on the island of Kythera, to discover more about the first Minoan peak sanctuary found outside Crete.

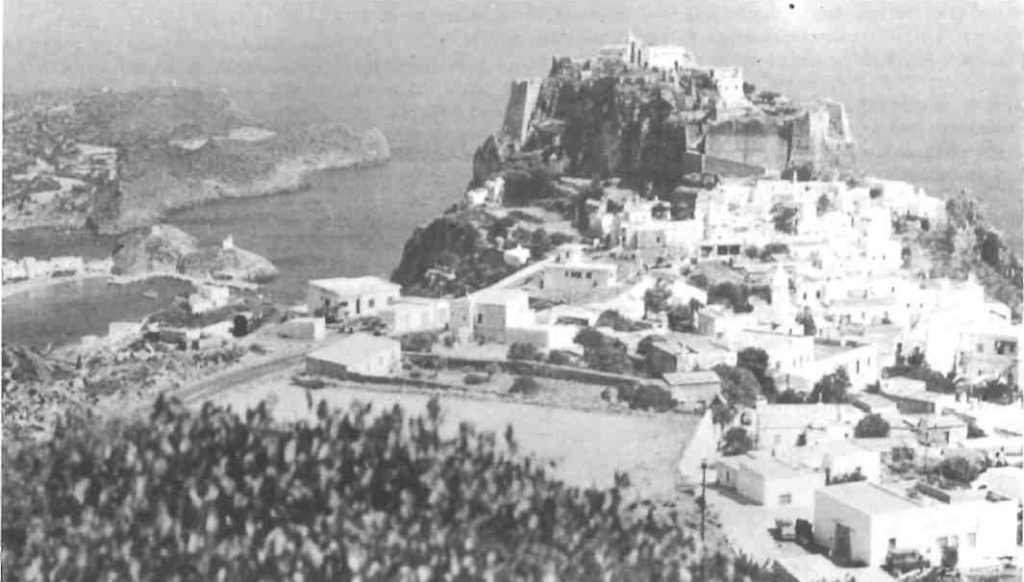

The sanctuary was probably the place of worship for Minoan colonists living at Skandeia on the Bay of Avlemonas and confirms the importance of Kythera as a link between the Minoan and Mycenaean worlds.

Those fond of Greek mythology cherish the hope that the excavations may shed light on the origins of the cult of Aphrodite practiced from ancient times until possibly the fourth century AD on the slopes of nearby Palaiokastro.

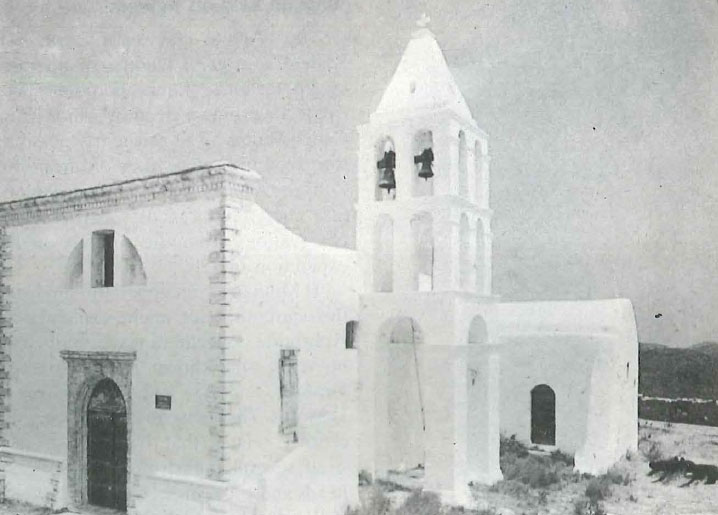

Discovery of the sanctuary followed the spotting of three small bronze statuettes in August 1991 by a visiting publisher/yachtsman. He had climbed to the 389-metre summit of Aghios Georgios to see the sixth-century mosaics of St George the Hunter, painted in the time of Justinian and preserved in the medieval monastery church.

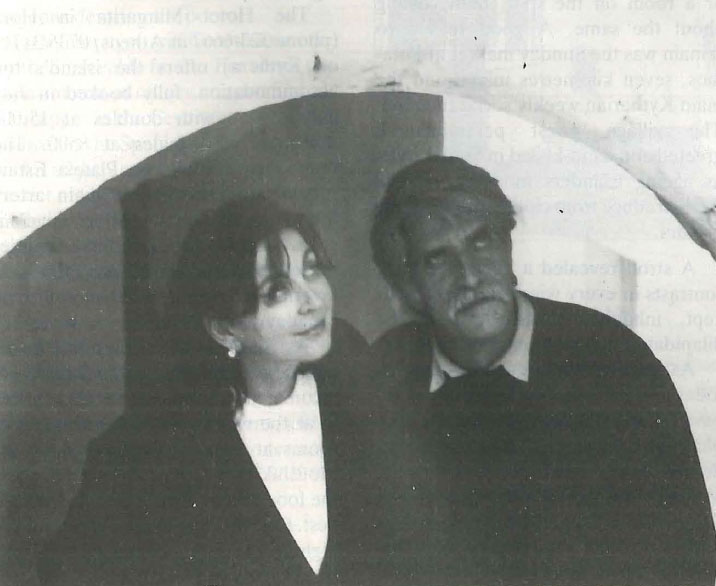

“It was a hot afternoon and the church door was locked, so I sat on the steps,” relates Adonis Kyrou, editor and owner of the Athens daily, Estia, and a keen amateur archaeologist. “The ground in front of the building had obviously recently been levelled for a terrace. The soil is light in color, and at the edge of the turned-over area by the steps I noticed a small dark object. I thought it was a plastic toy, but as soon as I touched it, I realized it was bronze.”

A search revealed two more figures. He identified them as Minoan votive idols, since he knew British excavations from 1963-65 had revealed a Minoan colony active for nearly 2000 years on the Kastri promontory in the bay below.

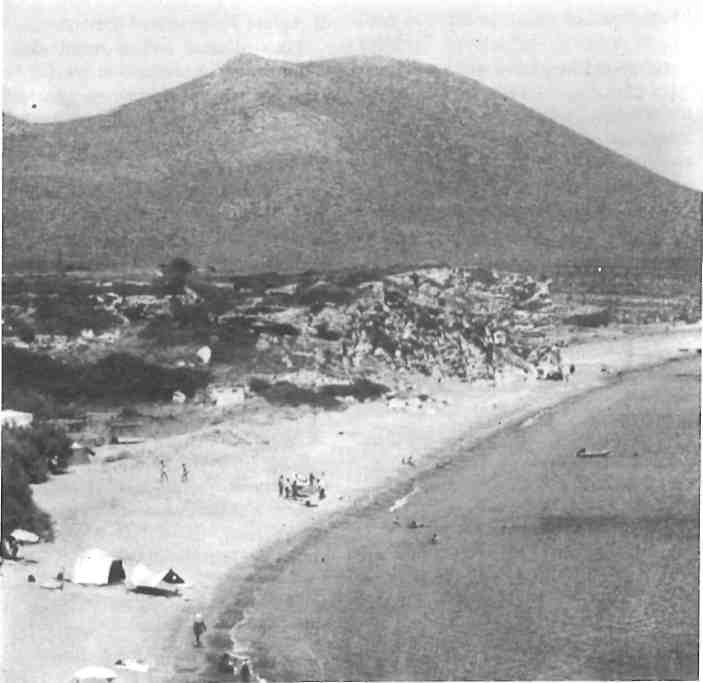

Remains of walls, houses and drains at the Kastri site showed extensive settlement developed from middle to late Minoan times. Pottery finds showed that colonists upheld Cretan ceramic traditions. Tombs found in limestone caves on the promontory were proof of Minoan-style burials.

Heaps of spiky shells of murex brandaris indicated production of the purple dye secreted in a gland of the mollusc, which when crushed and boiled, shells and all, with salt for several days (a smelly business) yielded one-sixteenth part of dye. This distinctive dark red or purple hue (called porphyris) was used to color royal garments.

Silver cups and a gold bead hinted at other links with Minoan palace culture, rather than an exclusively colonial society engaged in agriculture, fishing and the murex industry. “Such finds show the inhabitants of Skandeia were aware of the finer things of Cretan material life in the era of the thalassocracy,” says Dr George Huxley, a leader of the British expedition, now living at Oxford. An inscribed prism and a Linear A sign suggested at least some Skandeians were literate.

Bits of pottery dug up pointed to a transition from Helladic to Minoan habitation unique in the early Aegean world. “Kythera’s ties with the Peloponnese were severed as Cretan maritime influence grew,” observes Dr Huxley. But in late Minoan times, mainland influence reasserted itself. Minoans are thought to have abandoned the colony about 1450 BC when it is believed the volcanic island of Thera (Santorini) exploded and the entire Minoan culture collapsed, swept by fires, tidal waves and invasions. By about 1250 BC, the time of the Trojan War, Mycenaeans were in occupation. “But it is not possible at present to say what was the condition of the place in the age of greatest Mycenaean power and prosperity,” says Dr Huxley. Homer gives evidence for high-level comings and goings on Kythera, and it would appear unsurprising that Skandeia had a place of worship. Mindful of the legends, Mr Kyrou told the Sakellarakis, who are friends, that he had located a Minoan peak sanctuary on Kythera, and persuaded them to procure a permit for a trial dig.

The couple is known worldwide for excavations begun in 1964 at Archanes where discoveries include a large Minoan cemetery with unplundered tombs, one with the remains of a woman bedecked with 140 pieces of gold. Another discovered in 1975, contained remains of a noble lady adorned with a marvellously ornate gold necklace. Most notably, they unearthed evidence of human sacrifice, apparently interrupted by earthquake. Mrs Sakellarakis is completing a book on Aegean Bronze Age idols this year for publication by the Munich Academy of Sciences.

To their astonishment, a little spadework on Kythera turned up an unprecedented cache of 31 bronze Minoan votive idols on the hilltop, along with a fair amount of middle and late Minoan and Mycenaean pottery and other objects. “Some are big, some small. All are male. Not all are intact,” says Dr Sakellarakis. “Statistically alone the find is important, as even in Crete not more than five such bronze idols have been found together and a total of only 190 is known.”

The discovery, in his opinion, is a “tremendous addition to Minoan peak sanctuaries and highly valuable for study of Minoan culture, particularly of plastic art and dress.” Being bronze, these Kytherian adorants are evidence of cult practice from the late 17th century, continuing till the 14th century. The thousands of clay idols found at Cretan peak sanctuaries show pre-Bronze Age cult practice going back to the third millennium.

Such figures were deposited by devotees, who apparently believed they served as substitutes for themselves as continuous worshippers. These Minoan sanctuaries are sited on the highest point visible from main centres – Mt louktas for Knossos and Archanes and Kofinas for Phaistos. Aghios Georgios is the highest point near Kastri.

The plethora of figures surfacing on Aghios Georgios prompts Dr Sakellarakis to surmise that the sanctuary was used to spread Minoan religious propaganda to Mycenaeans. “In those days, religion was used to influence people for political purposes,” he says.

As a result of this new find, Aegean archaeologists are looking for peak sanctuaries near other Minoan colonial settlements like Akrotiri on Santorini (the largest site); Aghia Irini on Kea; Phylakopi on Milos; and a recently discovered site on Samothrace which has yielded Linear A tablets and important sealings.

The late American archaeologist John Caskey is known to have found an idol on top of the hill of Troulos on Kea during the 1960s and on Milos some finds suggest cult practice, says Dr Sakellarakis.

Idols found on Crete depict a sway-backed figure with a hand touching the forehead in salute and suggest a posture of worship. “It seems a gesture made while praying to the rising sun,” suggests Dr Sakellarakis.

Hardly less a mystery is how so many objects could have lain near the surface undetected for 3500 years. Kythera’s remoteness has perhaps helped. “Kythera is still almost a magical island lying in the realm of dreams,” says Dr Sakellarakis. “Life there is simple. The people preserve their character, unaffected by the world at large. Pilgrims have come and gone to the chapel of Aghios Georgios to light their candles for 1500 years, but it would never have occurred to them to scour round for antiquities. Even today there are no great waves of tourists to the island nor thought of smuggling, so these tiny votive idols lay there undisturbed,” Dr Sakellarakis said.

Several trenches will be dug this summer by a team of 30 Greek archaeologists, one to the south of the site where Minoan building remains rise above ground and another to the north. More evidence of Minoan culture may be unearthed, but Dr Sakellarakis makes no predicitons. “The excitement of archaeology lies in its complete unpredictability,” he says.

The Minoan presence has been evident on the island since 1914 when the Kytherian archaeologist Valerios Stais, an early curator of the National Archaeological Museum in Athens, found Minoan pottery and jewellery in tombs at Kionis, near Manitochori in the south of the island.

Also found was a stone vase inscribed in hieroglyphics with the name of the pharaoh Userkaf, ruler in Egypt from 2494-87. Other evidence for links between Kythera and Egypt is the inclusion of the island’s name in a hieroglyphic list of Aegean ports-of-call, between Crete and Nauplia, dating from the time of Amenhotep about 1400.

An intriguing question concerning the new-found sanctuary, says Mr Kyrou, is its connection, if any, with the renowned sanctuary of Aphrodite which flourished on the island. Eastern links may be significant in this respect, as Herodotus says the temple of Aphrodite on Kythera was established by Phoenicians from Syrian Ascalon, the site, he was told, of the most ancient of all temples to the goddess. Cypriots also claimed their shrine to Aphrodite at Old Paphos originated from Ascalon.

Pausanias adds his bit, noting that the sanctuary of the goddess on Kythera was “most sacred and the most ancient of all the sanctuaries of Aphrodite in Greece.” The goddess, he tells us, was “an armed wooden idol.”

Skipper of the black-hulled yacht Kalokyra, Mr Kyrou still studies the Aegean past, and the history of the Gulf of Argos is of special interest since his home port is Spetses, where his Cypriot-Greek family has a summer home. His enthusiasm and love for the area are evident in his book, published in Athens in 1990. At the Crossroads of the Argolikos is a goldmine of ancient history with detailed illustrations of the coastline.

The Aghios Georgios cape on Kythera is a great landmark and vantage point for seafarers, he points out, as the air is blown clean by winds from Cape Malea. The ancients possibly stargazed from it, as they did from Mt Zeus, or Zas, on Naxos. French explorers, he says, made astronomical observations from the summit on an expedition in 1780.

If Minoans worshipped the sun from this spot, the cult might explain why Aphrodite on Kythera was described as heavenly and known as daughter of Uranus, the sky god, he theorizes. Hesiod’s Theogony in the late eighth century relates that Uranus by Gaia sired several monstrous sons with 50 heads and 100 arms whom he hated and hid underground. At his mother’s behest, son Kronos rose in revenge, castrated his father and threw the genitals into the sea from whose “white foam the goddess came forth, lovely, much revered, and grass grew up beneath her delicate feet,” wrote Hesiod.

One of the 31 bronze Minoan votive idols excavated from the Aghios Georgios site last summer. Only 190 such idols are known to exist Later poets embroidered this account, describing Aphrodite zephyr-surfing ashore on a scallop shell escorted by Nereids and Triton, greeted by Eros and the Horai (seasons) and crowned by Peithos (persuasion or cunning deceit) with garlands of roses and myrtle. Sparrows and doves, symbols of fertility, fluttered round her and flowers and greenery sprouted underfoot.

Deconstructionists have debunked this classical image of the Minoans. “The strong Oedipal element in the Greek version suggests it rose in the period of guilt culture,” says scholar John Pinsent. “Aphrodite, goddess of desire, rose naked from the foam of the sea… She is the same wide-ruling goddess worshipped in Syria and Palestine as Ishtar or Ashtaroth, who rose from Chaos and danced on the sea,” wrote Robert Graves in 1955.

Commenting on Hesiod in 1966, Oxonian M.L. West said: “The birth of Aphrodite is a delightful sequel, an episode which has a certain dream-like quality… transforming an ugly scene into one of beauty… In dreams the mind moves freely, creating a fantasy in which thought and images are associated. So the myth of the birth of Aphrodite is a fantasy associating various elements. She is formed of foam, to explain her name. It is an excellent example of how a complex etiological myth is created.”

Walter Burkert in 1985 said tartly: “The birth myth is not a marginal extravagance of poetic fancy.” In his view the castration and throwing of the genitals into the sea were perhaps part of sacrificial rituals. He saw Aphrodite as thoroughly enmeshed in the Greek tradition of cosmogonic speculation. (Excavations round Ephesus have produced evidence of bulls being sacrificed and castrated, the severed parts used to bedeck the bodice of the gown worn by the goddess Diana as seen in countless replicas in Kusadasi).

Graves sensibly remarked: ‘The science of myth should begin with the study of archaeology, history and comparative religion, not in the psychotherapist’s consulting room.” He regarded Greek mythology as “no more mysterious in content than are modern election cartoons, and, for the most part, formulated in territories which maintained close political relations with Minoan Crete… a sophisticated country.”

He believed the Aphrodite cult entered Greece from Kythera because it was such an important centre of Cretan trade with the Peloponnese. What is more, he thought, the cult travelled from Crete because the Cretan Aphrodite was closely associated with the sea: shells covered the floor of her sanctuary at Knossos; she is depicted blowing a triton shell in the Idean cave; a triton shell was found in her sanctuary at Phaistos; and sea urchins and calamaria were sacred to her.

Aphrodite’s genealogy is usually traced back to the Semitic Ishtar-Astarte, goddess of love, war and vegetation, known as queen of heaven, and accompanied by flights of doves. In tracing the cult back to such a divinity, the scholar Lewis Richard Farnell, writing a century ago, noted Phoenician links to its practice in Attica, at Athmon, introduced by King Porphyrion (the purple king), an archetypal Phoenician trader. He also points to Thebes, where Aphrodite was associated with Cadmus, the mythical city founder from Phoenicia.

Questioned about possible links between the Minoan and Aphrodite sanctuaries, Dr Sakellarakis is the very model of a modern scientific archaeologist. “What do we know?” he asks. “We really don’t know much about the cult of Aphrodite. Having now established the existence of such an old cult as the Minoan on Kythera, we have still to find out what the connections might be between the two.”

The Phoenicians emerged in the ninth and eighth centuries, he says, and engaged in the porphyry trade. It would be logical for them to stop at Kythera on their voyages to the western Mediterranean, to Sicily, to their great colony, Carthage, and as far west as Cadiz, bringing back olive oil, timber, textiles and pottery to Aradus, By bios, Sidon and Tyre. “They were a sea people and knew where to stop,” he says. He is researching possible links between Phoenicians and Crete, but has no evidence as yet where the cult originated.

Surprisingly, no systematic excavation has been done on the site identified as being the likely location of Aphrodite’s ancient temple on the south-west slope of Palaiokastro. The British dug there in 1887-88 and Heinrich Schliemann thought the temple must have been near the church there of Aghioi Kosmas and Damianos.

Four columns and an upside-down architrave block used as the lintel of the west door in the church are generally thought to have come from an Archaic Doric temple, but it appears to have been about 400 metres west. Dr Huxley favors a terrace site halfway between the church and the summit, a spot shored up by a wall of big polygonal blocks, possibly Archaic. Another scholar, Judith Herrin, believes the temple was still an attraction as late as the fourth century AD.

The island of Kythera is caught in a sea of cross-currents in every sense – geographically, culturally, socially, and historically. Its rugged limestone coast is washed by five seas, the Ionian, the Aegean, the Cretan, the Libyan and the Mirto, all merging where Kythera lies, five miles off the Peloponnese. The crossing has a reputation for being treacherous. “I would have come home unscathed to the land of my fathers,” recounted Odysseus, “but as I turned the hook of Malea, the sea and current and the north wind beat me off course, and drove me on past Kythera.” So began his years of wandering.

The island has hosted so many refugees over the centuries and suffered such massacres of its population by pirates, real Kytherians hardly exist, says Nikos Lourantos, a typical islander. Of Venetian stock, he was born in an outback town near Canberra, settled on the island of his parents in the tiny Kytherian capital, Hora, at age five, and now teaches English and acts as a roving Byzantine antiquities guide on the island for the Ministry of Culture.

Many Cretans fled to Venetian-held Kythera once the Turks took Herakleion in 1669. Few stayed long. Venetian rule was oppressive, and most moved to more prosperous northern Ionian islands.

“No one living on the island wants to stay,” says Christos from Amphilohia on the western mainland, who for 12 years has run a popular art and antique shop in Hora half the year, fishing back home during the winter. “But Kytherians anywhere else want to come back.”

The population shrinks in winter to 2500 scattered in 90 villages. In some only one house may be occupied, says Mr Lourantos, the rest deserted by owners now living in Australia. “At least 20,000 Kytherians have settled round Brisbane. Many have made a lot of money, moving from catering and general stores begun in the 1950s to property speculation in the last 20 years.” Expatriates have built a hospital and large old people’s home in Potamos. Many summer on the island and in their old age return, to be visited by back-packing young relations from Down Under.

Julia Kritikos, a Tasmanian economist, and her Launceston fiance stayed last summer with two of her elderly uncles, retired from Australia to a patriarchal home in the village of Milopotamos. One had been an orchestral violinist, and to entertain his guests played on his old Italian fiddle, bought for two pieces of gold in pre-World War I days from a Venetian music trader on the island.

Such island lore is easily picked up on the two-hour ferry trip aboard the Martha from Gythion to Aghia Pelaghia. Rosemarie, a Swiss native, resident for 15 years in Kapsali, gave an insight into island society “I survive it because I go back to Zurich and work as a nurse in a hospital ward for three months each winter,” she said. “Other foreigners suffer from never getting away.” (Winter whisky-drinking is a particular snare, she remarked.)

Arrivals in Aghia Pelaghia find no public transport, apart from school buses. “Nine taxis serve the island. The drivers want to keep it that way,” said Takis Kladakis, of Cretan stock, born and bred in Alexandria, now married to a Belgian and living in Ostend after 15 years at sea on Niarchos tankers. He spends a late summer month each year on the island, doing maintenance on a family village house.

A choice could be made between a taxi for the 33-kilometre drive to Hora or a room on the spot, both costing about the same. A good reason to remain was the Sunday market at Potamos, seven kilometres inland and the main Kytherian weekly social function. The village priest perambulated, greeted and hand-kissed in feudal style, as ageing islanders modestly offered fresh produce from cloths spread on the ground. A stroll revealed a village of stark contrasts in every winding street, well-kept, inhabited homes next to the dilapidated hulks of emigrant families.

As part of the Piraeus nomarchy today, Kythera is blessed with newly paved roads- which have allegedly doubled traffic accidents, and a 63-million-drachma restoration scheme for the old Venetian village of Milopotamos. An EC grant has funded a modern sewage system, though not helped solve the chronic water shortage.

Like other Ionian islands spared Turkish occupation, Kythera’s records cover the period of Venetian rule from 1207 until 1797, and it was a British protectorate from 1809 until 1864. In historical importance, the documents are ranked second only to Corfu’s. These archives are kept in the former Venetian governor’s residence inside the majestic fortress dominating all views of Hora. A young classicist from Piraeus, Evanthia Skopeta, a Ministry of Culture employee, has been trying to collate them, directed by Byzantine scholar Chryssa Maltezou of Athens.

While Kythera’s ancient fame attracts amateur archaeologists, treasure-hunters might descend: “A Kytherian pirate confessed on his deathbed to a priest in Constantinople late last century that he had hidden two big pots of gold near Melidoni, on the south coast,” says Mr Lourantos. “Only one has been found.”

To complement tourism, he favors industrial development like improved methods of honey production. “Byzantine families in Constantinople used to charter boats to come to Kythera and load up with honey,” he recalls.

Kythera is connected to Athens by daily Olympic Airways flights and, from May to October, by twice-weekly Flying Dolphins. A ferry calls throughout the year on the route between Piraeus and Kastelli in western Crete, currently the Milos Express, replacing the lonion which ran aground in fog on Gramvoussa last October. In high season, there are calls at both Aghia Pelaghia and Kapsali. A local ferry, the Martha, links Aghia Pelaghia with Gythion.

The Hotel Margarita in Hora (phone 323-6667 in Athens, 0735-31711 on Kythera) offers the island’s top accommodation, fully booked in July and August with doubles at 15,000 drachmas and singles at 8500. The brand new Castello on Plateia Estavromenou, where Hora’s main artery forks for the kastro, offers spacious rooms with views and cooking facilities for less. Zorbas, Hora’s one off-season taverna, is closed, like the museum, on Monday.

At Kapsali, the Aphrodite apartments a block above the beach are recommended, as is the taverna tucked in at the wharf end of the beach. For rooms at Aghia Pelaghia, ask at the Moustakias taverna-cafe-ouzeri, where the food is basic Greek island fare at its best. One needs to reserve a bed for the night in order to be at the wharf in time for the early morning boat to Crete.