The ancient age of heroes had no heroines, according to American scholar Moses Finley. So as the word ‘hero’ had no feminine gender, we may talk only of hero-worship from that glorious, if chauvinistic, period.

Yet Odysseus and Achilles aside, no figure from the age won a more worshipful following than Helen of Troy. Homer institutionalized if not instituted her cult, beginning with his account of admiring Trojan elders sitting with King Priam on a tower by the Skaian Gates, watching their sons being slaughtered by Greeks.

Upon sight of Helen in her shimmering garments, the non-combatant old warriors are described as whispering in awe: “Terrible is the likeness of her face to an immortal goddess. Surely there is no blame on Trojans and strong-greaved Achaians if for a long time they suffer hardship for a woman like this one.”

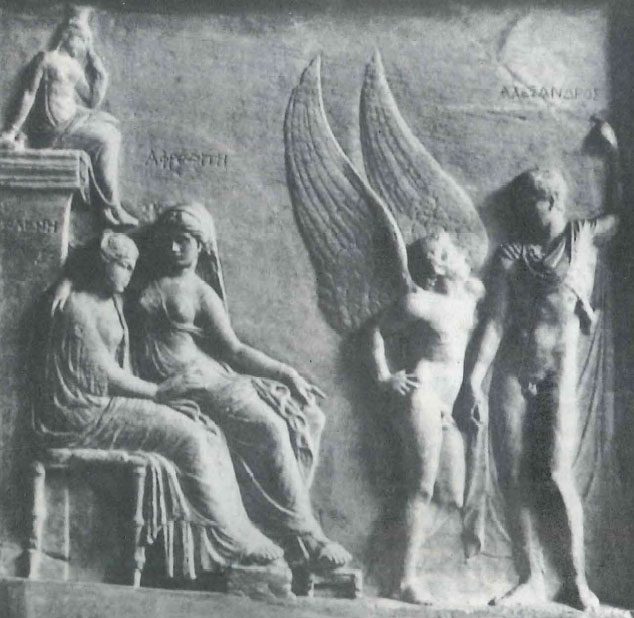

To Paris, or Alexandros as Homer usually calls him, Helen’s beauty was less the point than “the sweet favors” of Aphrodite. Taunted on the battlefield by his brother, Hector, for being woman-crazy, he answered rebukingly: “Never to be cast away are the gifts of the gods, magnificent, which they gave of their own will, no man could have them for wanting them.”

As if siding with Helen, Homer reserves for her what he rates the greatest good in life for women, “a husband and a house and sweet agreement in all things, for nothing is better than this, more steadfast than when two people, a man and his wife, keep a harmonious household.” So Odysseus told Nausicaa in the Odyssey.

With her consort, Helen is portrayed in comfortably affluent, postwar domesticity in Lakedaemon, when Telemachos visits seeking news of his father. The young lthacan marvels at their high-roofed, echoing mansion gleaming throughout with bronze, gold, amethyst, silver and ivory, complete with smooth-polished bathtubs.

Some of the treasures were souvenirs of their eight years of travel through Cyprus, Phoenicia, Sidonia, Egypt and Ethiopia after the war, according to Menelaos. Helen joined in the conversation, settling down to spin with a gold distaff beside her wheeled silver workbasket edged with gold, a present she received in Egyptian Thebes.

The couple note the likeness between father and son, tell of Odysseus’ disappearance, then after due grieving, share with their guest a repast washed down with wine into which Helen put ‘medicine of heartsease’ to drown all sorrow, another gift from Egypt.

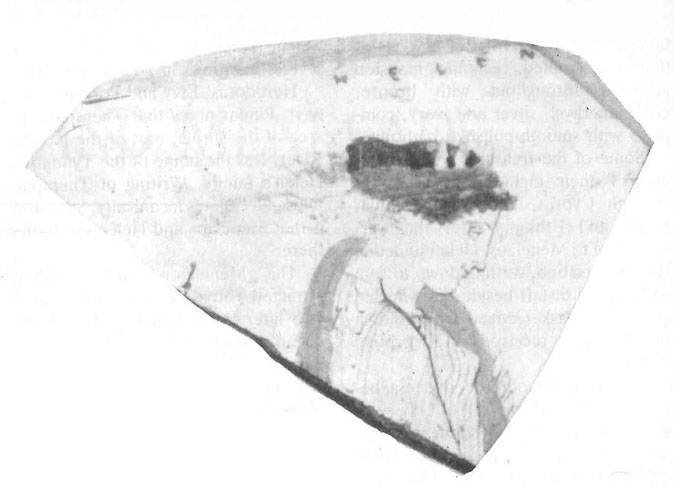

Later Greek literature tends to take up the theme of Helen’s culpability, rather than her immortal beauty and housewifeliness. In The Trojan Women, Euripides endows her with quite casuistical dialectic ability: the whole bad business of the war was Hecuba’s fault, she says, because she gave birth to Paris who abducted her. But the traditional view of the daughter of Zeus hatched from an egg is perhaps epitomized in a red-figured vase painting: Menelaos is depicted so bowled over by his long-lost wife’s beauty, that he drops his shield when he first sees her again.

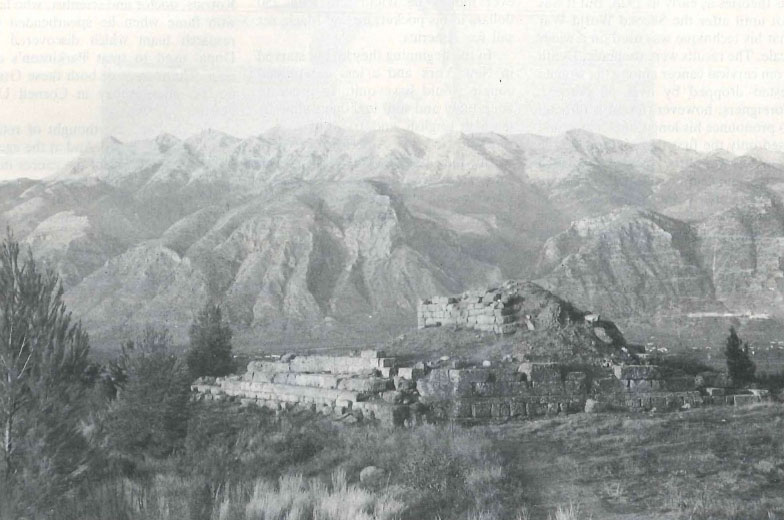

Twenty years have passed this month since definitive British excavations began into Mycenaean remains beside an Archaic seventh-century BC shrine to Helen and Menelaos on Mount Parnon overlooking Sparta. But archaeologists still do not agree on precise identification of the hewn-stone Bronze Age ruins.

The excavation director, Dr Hector Catling of Langford near Oxford, and the British School at Athens director from 1971-89, believes that what now lies exposed is the remains of the principal Laconian settlement of the 15th and probably also of the 13th century BC. If so, what bursts rewardingly into view after a steep climb could be foundations of the magnificent mansion that so impressed Telemachos.

Classical scholars digging in Laconia have naturally sought keenly for the home of the Spartan royals, since Heinrich Schliemann in 1876 showed that Mycenae broadly tallied with the Homeric description of the house of Atreus. They had a clue since the Archaic shrine to Helen and Menelaos which remained visible, had earned several mentions in ancient writings.

Herodotus, Livy and Polybius refer to it. Pindar notes that Therapne, the area of the shrine, east of the Evrotas River, was the home of the Tyndarids, Helen’s family . Writing of Therapne, Pausanias relates laconically, “the story is that Menelaos and Helen are buried there.”

The Menelaion shrine perhaps attracted votive offerings continuously into later times because of its Mycenaean remains, suggests Richard Catling, who worked with his father on the site. The building of the shrine at the turn of the seventh century would have consolidated the tradition linking it with the supposed burial place of Helen and Menelaos. The Spartan state possibly played a role in transforming what had been a centre of an unofficial cult into a major public sanctuary.

Father and son agree that erosion, compounded by a severe earthquake in 464 BC, has dealt harshly with the site, radically changing the lie of the land. Building remains on the edges show the hilltop must have once been broader. Soil chemistry has also meant most pottery finds are in deteriorated condition.

Another British archaeologist in Greece, Dr Colin Macdonald, curator at Knossos for the last two years, also believes that Archaic age Spartans must have associated the place closely with their great Bronze Age ancestors sung of in the J:Iomeric poems. “If Helen and Menelaos existed, they’d have inhabited that place which their descendants believed they were associated with,” he says.

Schliemann had inspected the Archaic shrine but noticed no evidence of Mycenaean occupation. Neither did Christos Tsountas, excavator in 1889 of the Vapheio beehive tomb down on the plains which yielded up the famous gold cups of the Tame and Wild Bulls.

The only ruins to be seen in the 1880s up on the spur were of the Archaic shrine, partly investigated by the early German archaeologist Ludwig Ross in 1833, further explored in 1899 by P. Kastriotis.

British archaeologists working in Sparta in 1909 were prompted by village tales of regular surface finds to loQk: again at the Menelaion site. R. McG. Dawkins, British School director 1906-14, first mooted the idea there might be a late Mycenaean settlement up there. In May and June 1910 a team of 20 or 30 archaeologists and workmen, including Professor Alan Wace, brought to light Mycenaean remains in a striking location on the red, waterworn scarps.

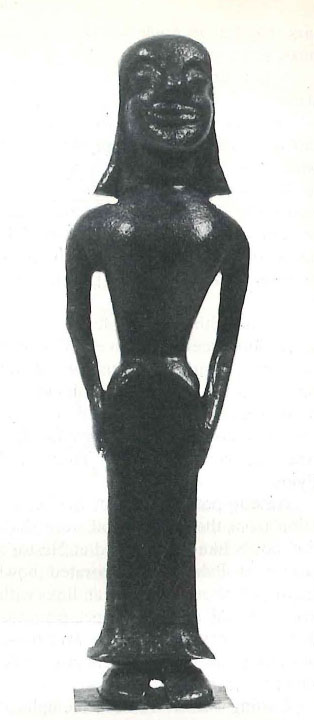

The buildings, estimated to date back to the 15th century BC, were destroyed by fire 200 years later. Among finds were late Mycenaean pottery such as clay sealings and a terracotta, Minoan-style female figurine. Around the Archaic shrine were found various bronze, lead and pottery votive offerings.

In a survey of Mycenaean sites in Laconia published in 1966, Helen Waterhouse and R. Hope Simpson concluded that the Mycenaean remains up at the Menelaion must have been the site of Homeric Sparta. Not enough Mycenaean finds have been made in the area of classical Sparta to suggest important Bronze Age habitation, they said. The only other site contending for the honor might be Palaeopyrgi, near the Vapheio tomb. They believed at least a grand mansion awaited discovery in the vicinity. Olive cultivation is so intensive, though, it is hard to see where or how it could be done.

Greek explorations in Laconia led the Sparta antiquities service, Katie Dimakopoulou especially, to encourage the British to broach the Menelaion site again. In May 1973, Dr Catling began his digging, funded by the British School with support from the British Academy, the Cambridge classics department, the Carnegie Trust and Oxford’s Craven Fund.

By 1977 Mycenaean buildings of considerable sophistication had been unearthed, with signs of relatively luxurious internal appointments. “That such a building could be conceived and executed in Laconia in the second half of the 15th century is of much historical interest,” he wrote.

Ploughing in 1971 had turned up mid-to-late 15th century finds. Other chance finds in 1978 during agricultural work by Afyssou villagers, who own surrounding land , included fragments of Vapheio-style cups with tortoiseshell ripple decoration, Palace-style jars, handmade goblets and Late Minoan pottery imports.

Major replanning of the settlement seems to have occurred at that time, which Catling cautiously links with the fall of Knossos. He agrees with those who think that event was a watershed in the Aegean late Bronze Age. “It opened to the princes of the mainland unlimited access to the raw materials and luxury goods available in the markets of Cyprus and the Levant,” he says.

By the 13th century, aesthetic considerations seem to have influenced building, judging by the use of red and blue schist slabs to enhance a monumental terrace wall. The civilization then ended with catastrophic destruction, as at Mycenae, Tiryns and Pylos.

Among pottery finds at the Menelaion from the final period were shallow bowls like some found at Nestor’s palace at Pylos and decorated bowl fragments showing Laconian links with Argos, fitting in with a prince from the house of Atreus, such as Menelaos, marrying into the Laconian royal family.

Catling warns: “Too much emphasis should not be put on the legendary background to all this, but it is of interest.. . in view of the closeness of the relationship between the kingdoms of Mycenae and Sparta in Homer’s Greece.” The Archaic shrine was a tile-roofed building of carefully cut blocks, so excavation evidence shows. Catling describes it glowingly as “one of the most arresting landmarks in the region.”

Substantial as it seems, what we have is only a fragment. Once there was a broad, lofty platform held in place by massive conglomerate blocks, enclosed at the top by a blue limestone and marble parapet, triglyph and metope freize on the north side. “At the centre, all vanished save arough foundation, stood a temple of honey-colored poros blocks,” Or Catling explains. “Its gable, roofed in dark terracotta tiles, had at either end a polychrome akroterion, also terracotta, with a Gorgon’s face at its centre.” This stood at the wesf end of the plateau, close to where the Bronze Age buildings had been. “The spot has a breathtaking view of the Evrotas valley and the peaks of Mount Taygetus and from a subjective point of view would have attracted the most important buidlings,” he observes.

Among votive offerings dug up in 1975 was a seventh-century bronze aryballos (perfume bottle) inscribed with the words: ‘Deinos dedicated this to firmed that the place was the shrine of Helen, wife of Menelaos.’ Also found Helen mentioned by ancient writers, was a harpax from about 470 BC with In the 1976-77 digging, archaeologthe words, ‘For Helen’. These conists found a small early fifth-century blue limestone stele at the bottom of a cistern. The inscription read: ‘Efthykrenes anetheke to Menelai’, seen as evidence for the cult of Menelaos at the shrine, too.

Digging in 1985 turned up finds from a spindle whorl and loom weight, seen as apt offerings to Helen in her middle-aged domestic role, plus 169 bronzes, 48 terracotta figurines, 25 lead and 10 iron objects, 200 pot fragments and Corinthian imports.

Catling certainly believes that what has been revealed was the main Mycenaean centre in Lacedaemon. He finds it hard to imagine the shrine location was pure coincidence, feeling sure the cult arose from reverence for the past, perhaps given impetus by the advent of the Homeric epics.

His successor as director of the British School at Athens, Dr Elizabeth French, daughter of Alan Wace who had been part of the 1910 excavation team, finds it equally hard to believe such an elevated and inaccessible spot was likely to have been a major administrative centre. She argues somewhere round Palaeopyrgi is more likely, more like other Mycenaean sites.

Dr French allows that a Menelaion Bronze Age mansion might have been a holiday retreat. The indulgentminded might fancy Helen entertaining Paris lip there for a weekend, before they headed for the islet of Kranae, in Menelaos’ neglectful absence in Crete, as Euripides’ Helen says was the case.

If the ayes have it, those who arrive up at the site may imagine themselves at the heart of Lacedaemon. They may think, too , as Catling urges, “of the world to which the buildings once gave expression, a world dimly mirrored in Homer’s account.”

Similar continuity is supposed at the nearby Amyklaion, an Archaic and Classical shrine to Apollo where a sanctuary flourished till the 12th century at what was believed to be the burial place of Hyakinthos, an early deity not originally associated with Apollo and probably of Cretan provenance, scholars say.

For those in search of other places in the southern Peloponnese with Bronze Age links, Aphrodite’s beloved island of Kythera is becoming a happy hunting ground. Homeric Skandeia has been identified on the Bay of A vlemonas by British archaeologists working in 1963-65. Pottery evidence there shows increasing Mycenaean influence on the long-established Minoan settlement in the Trojan War period.

Aphrodite was honored at a shrine probably on the southwest slopes of Palaeokastro, inland west of Skandeia. Several pieces of an Archaic Doric temple are built into an early Byzantine chapel to Aghioi Kosmas and Damianos nearby.

Kythera was Christianized early and the pagan shrine to Aphrodite sternly and thoroughly demolished, says an island Byzantine antiquities service curator, Nikos Lourantos. He relates a popular Kytherian legend that Helen was chief priestess at an early shrine to Aphrodite on the spot. Rituals required that she officiate naked. These sacred rites were known all over the Aegean Bronze Age world.

If Helen were half-Minoan, what is more natural than that she should take part in rituals at least bare-breasted at the shrine of the goddess whom some speculate was originally from Crete. A visit to the shrine by Paris was in order, as he had been promised Helen, the most beautiful woman in the world, as his bride. This was the reward for his judgment that Aphrodite’s beauty surpassed Hera’s or Athena’s. “Paris saw Helen there, fell in love with her, and that’s how it all began,” says Lourantos.

Sceptics might look up Sir Richard Guylforde’s report of his visit in 1511 to Kythera where, he says, “Helena the Grekysshe Quene was borne, but she was ravysshed by Paris … doynge sacryfyce in the Temple for whiche rape folowed the distruccion of Troye.”

A castle of Menelaos is said to have been located on Palaeokastro between Mitata and the sea. Pehaps Leda holidayed there, solo, in earlier days, and, like her daughter later on, offered hospitality to a visiting foreigner. In a different context, Dr Catling has explained that Bronze Age Greeks claiming divine paternity were indicating politely their mothers had been raped by foreign invaders. Leda perhaps engaged the attentions of a Minoan trader passing through Kythera.

Further Greek excavations this summer at the newly discovered Minoan peak sanctuary north of Skandeia may help shed light on this entrancing prehistoric puzzle. More evidence may be found for what Catling hints at as a Mycenaean renaissance in the 15th century BC. As a link between cultures it might be compared to the 15th-century at Mistra, just opposite the Menelaion across the Evrotas valley, where the last rays of Byzantine civilization gave light to the Renaissance.

The Byzantine court at Mistra of course helped channel ancient Greek culture, the philosophy of Plato in particular, into western Europe. Mycenaean Lacedaemon, it seems, was possibly an equally vital route for bringing the original European culture into the mainstream of classical Minoan/Mycenaean Greek life. The mythology thrown up in the process offered golden material for Homeric poetry, remaining a perennially heady stimulant for leading figures excavating the Greek past.

The Menelaion may be reached from the Tripolis road north of Sparta turning right just past the bridge over the Evrotas river and following a steep track off the Yeraki road. From the town, the site may be identified up on its promontory on Mount Parnon directly opposite Menelaou street. Buses for Yeraki leave at 6:30 am and 1 pm weekdays outside the Maniatis Hotel, Palaeologou 61. Walking takes a little over an hour from bridge to site.

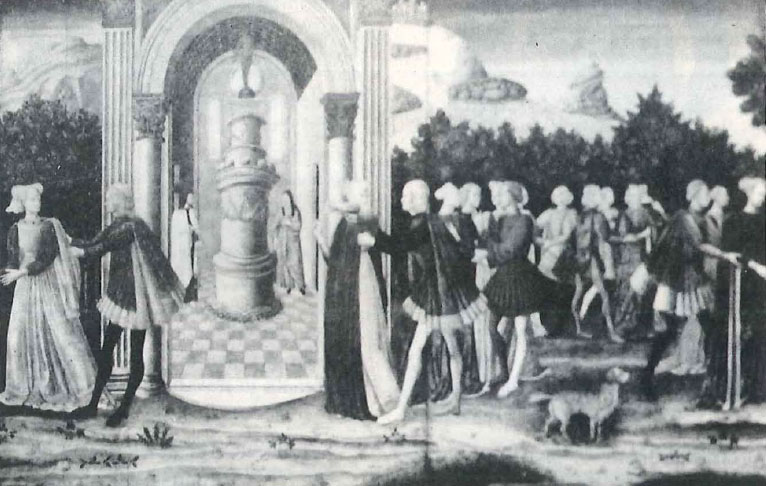

The Meeting of Paris and Helen

The fateful encouter of the lovers whose illicit passion instigated the Trojan War was colorfully described by Raoul Lefevre in his Recueil des Histoires de Troie in 1464:

When Paris knew of this feast at Kythera he took his best clothes and did them on and also took the best appearing and most cleanly men he had. And he went to the temple and entered it in a fair, sweet manner, and made his offering of gold and silver with great generosity. Then Paris was looked at hard by all who were there because of his beauty … So far went the tidings of the earnings of these Trojans and of their beauty and fine apparel that Queen Helen heard them speak thereof. And then, after the custom of women, she had great desire to know by experience if it were the truth that she heard.

And she determined to go to the temple under cover of devotion to accomplish her desire … When Paris knew that the Quyen Helen . .. was come to the temple, he arrayed himself and his company in the most lordly style he could, and went to the temple . .. And when he came and saw her he was greatly smitten with love, and began to look at her intently, and to desire to see the fashion of her body, which was so fazr and altogether well shaped that it seemed to all who saw her that nature had made her to be beheld and seen … And they looked at each other so long that it seemed as though Helen made a token or sign to Paris to approach her.

That night the Trojans … took all of those that they found in the temple and all the riches that were therein. And Paris with his own hand took Helen and them of her company and brought them to the ships.