Antonis Tritsis was born on Cephalonia in 1937; he died in Athens in 1992. During his short trip on this planet, he had the time to do quite a few things, some of which helped change the face of this country. He did it against all odds for he was a good horse that never stumbled.

He started his architecture and engineering studies at the Athens Polytechnic whence he graduated in 1960. He then continued his research at the Illinois Institute of Technology (IIT) in city and regional planning. He received his Master’s Degree in 1963, and his PhD in 1969. He was then. accepted as associate professor at the IIT where he taught urban and regional planning during the academic period 1969-70. Thereafter, he became involved in urban planning on an international level, as project manager or chief consultant in a series of undertakings in the United States, Latin America, Europe and even Africa. He often said he was fond of travelling, so he never minded getting on an airplane to go and oversee ventures on the other side ot the planet. And that’s what he did.

In 1976, he returned to Greece and became professor at the Postgraduate Institute for Regional Planning at the Panteios School of Sciences in Athens. The country was then in a state of democratic restoration. The years of dictatorship were a matter of the past and the King was voted down. New political movements were born and people had high hopes for the future.

A few months after Greece joined the European Community in 1981, the conservative government of New Democracy lost elections to ascending PASOK. George Rallis, outgoing prime minister at the time then uttered the greatest words of his career: “I hope the Greeks will not regret this!”

The epoch of hazy populism and shabby politics started. Antonis Tritsis was one of those who believed in socialist allaghi. He was elected member of parliament with the populist jumble because, as he later said, he was “taken in by the movement.” Indeed he was, and luckily so, for he became Minister of Urban Planning, Housing and the Environment. During his term, 1981-1984, this country was to experience some of the most sophisticated urban planning it had ever undergone. This was due not to the Pasokian Tritsis – he was never really one of them, as he later said – but to the man who had always dreamt of serving his country as an urban planner.

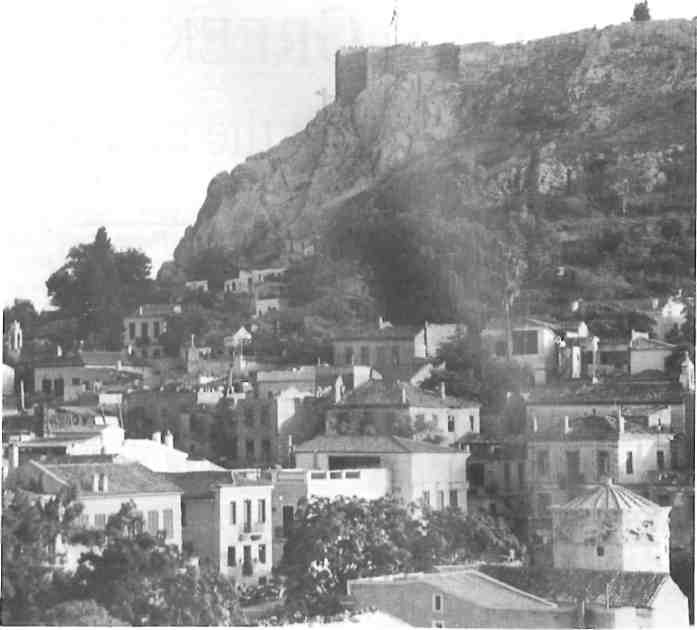

To mention but a few reforms he had worked hard to implement, let’s just look around Plaka. What you see is what Antonis Tritsis has performed on the ground. The whole area of Plaka was a third-rate tourist red-light ghetto before his time. He saved it from disintegration and made an urban quarter of archaeological, architectural and cultural interest in the heart of the capital which has no equal elsewhere in Europe. So much so that real estate prices have shot up to unreasonable heights.

When he came up with the idea to save Plaka, no one stood on his side. They all stood opposing him, ‘friends’ and foes alike, with a sarcastic grin. Yet, he succeeded. As Tritsis many years later said: “I did my duty and come what may!” Who, today, would not want to live in Plaka?

It surely is not redeeming from oblivion another Tritsis reform concerning urban and land planning, for it is still in power. Anyone wanting to construct anything anywhere in Greece must own at least 4000 sqm of land. In an urban area, construction plans are based on a combination of local construction possibilities and town planning regulations. We all know and we all are witness to the ugliness of what they call modern architecture should it be compared with the architectural excellence we inherited. Antonis Tritsis introduced new laws that would help the owners of older beautiful buildings refurbish their property with the financial support of the ministry. That is how a great deal of the remaining old buildings in Athens were saved from destruction.

It seemed his so-called friends in the populist jumble he was involved with did not like this. They got rid of him their way. However, that was not the end of his political career. In 1986, he becomes Minister of Education and Religious Affairs. His culture could not tolerate the perpetrated in the schools and universities by the populist apparatchiks. Antonis Tritsis spoke Greek, English, Spanish, Italian and, to a lesser degree, French. He thus came up with the idea to teach young primary school children Ancient and Byzantine as well as Modern Greek. He was the first person to advocate such an idea which only today is starting to be implemented. At the time, just mentioning it was a crime de lese majeste. His ‘friends’got rid of him once and for all with the manners that distinguish them from the rest of humanity.

He did not want to leave the Greek political scene, so he created his own Radical Party, was elected, and served in parliament until 1989 when he decided to take it easy for a while. “Just sit and think,” he later said. It did not last long because he was not the kind of man who can just sit in his corner and watch “them muck everything up.” His experience with the populist jumble had cost him a lot. He had decided he would be the perfect adversary in upcoming local elections against one of his former friends, a dedicated enemy of the time, for the position of the mayor. Athenians voted for him, and in October 1990 Tritsis became mayor of one of the oldest cities in the world.

He had prescience: a project and a plan for putting back Athens where it belonged in the train of history. The grandeur of his plan could only be equalled by the size of the problems this city was facing. He knew what to do; he knew how to do it. He moved into the mayor’s office in Liosion Street and worked hard. But it is the money that makes the mare go, and he inherited none of it. The previous mayor had indebted the city to such an extent that it was on the verge of bankruptcy. How was he to do anything without that calamity called money!

He thought that the government should help support all the ministries which were lodged in Athens; that they should pay for the services rendered by the municipality. Besides, he was elected with the help of the same government. He thought: charity begins at home. One more time, he was proven to be wrong.

He visited the office of the Prime Minister twice to make him give the Athens Municipality some 10 billion drachmas to help get started. He that goes a-borrowing, however, goes a-sorrowing. He was rebuked once, twice, all the time. Antonis Tritsis was not the kind of person who would give up. If the central government did not want to help, then the private sector would be invited to finance his projects.

Many industries gave a helping hand. A pilot project for mechanized refuse collection was implemented in the Koukaki neighborhood free of charge. Private companies offered the bins and collectors, but the Ministry of Commerce did all it could to delay the import of the gift to the municipality on the ground that the machinery was not produced in Greece.

The municipality collected all the old wrecks that littered the streets of Athens. Bulk object were also gathered and sent to the landfill. Curiously enough, instead of making them happy that Athens was getting cleaner, Greek politicians and journalists alike made fun of “the dustman Tritsis” in every way they could. They laughed their heads off when he announced that he would use Athens’ subterranean reservoirs and wells to clean the streets, water the parks and save energy. Now, the Water Works are doing just that, and nobody is laughing!

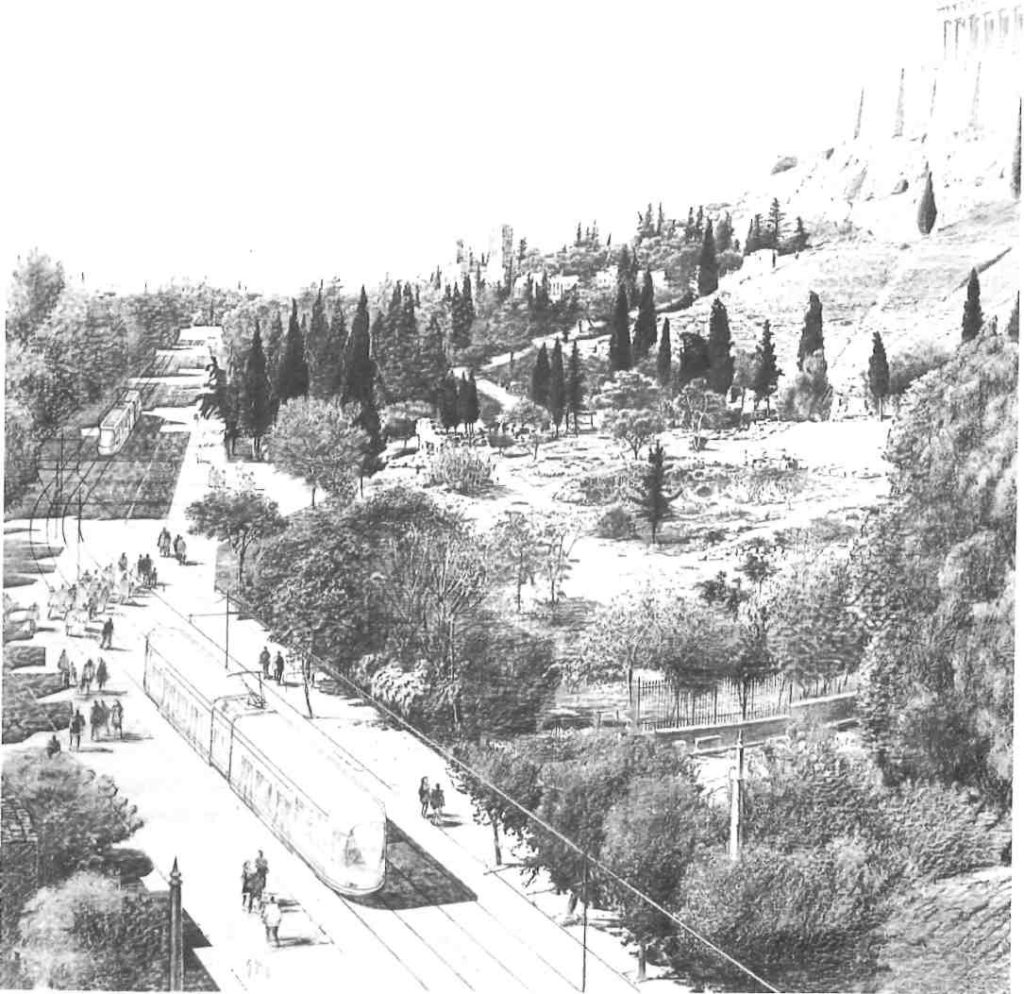

Antonis Tritsis wanted to reassess the social, economic and cultural character of what he called the historic center of Athens. His idea was to redefine the commercial activities along more social and historic lines without fundamentally hurting anyone. It was not enough to have shops in the centre of Athens. People had to return to reside in order to give the neighborhood a human face and limit, if not eradicate crime. He wanted to combine this with the creation of one extended park that stretched from Plato’s Academy through the ancient Kerameikos Cemetery, across the Acropolis and Philopappos Hill, passing through the Zappeion Garden to the Panathenaic Stadium.

Above all he wanted to redesign the plan which included the famous olive groves lying near Tavros, southeast of the center of Athens. This area is a source of continuous pollution as it harbors illegal factories and industrial plants. More than two thirds of it, however, is still green and can be used to create a tremendous park right in the middle of the Athens plain. Tritsis had a plan ready for the taking. Once again, from the government which helped elect him. The idea was to create an urban area where industry and commerce could coexist in a large garden which would harbor social activities as in a neighborhood. The cost was too high, he was told, when they were not merely derisive.

Besides the Acropolis, Athens is world-famous for pollution. The municipality created atmospheric monitoring stations to assess and measure the origins of pollutants. Like everywhere else, cars are the source of most poisons we inhale. Tritsis had a plan: a tram system that would limit automobile transport in the whole center of the city. This was a project he had in mind when he was Minister of Urban Planning and one of the reasons he was discharged. They all laughed at his tramaki.

The project is still there, and many companies have already expressed great interest in designing and constructing at least Stage One of the Athens Tram. The EC is also willing to finance the whole project if necessary. But it will still be Tritsis once scorned tramakil Antonis Tritsis wanted Athenian schools to be exemplary in every way: the quality of education, the technological training and the cultural bases. “Athens has a history no other city on earth has,” and the Mayor Tritsis was planning to start an open university, another opera house, yet another theatre and many cultural and research centres for the study of Hellenism, Orthodoxy and the Olympic Ideal.

Although eminent in many ways, Tritsis above all had a plan, a project and an ocean of ideas all of which were plausible. He knew what he was talking about. Surely this must have been the reason why politicians and journalists alike hee-hawed at his ideas. They could not stomach the thought that he was not the ass in the lion’s skin.

Mayor Tritsis died of a stroke a year ago. He left a former wife and two daughters. But he mainly left an incomplete travail: the restoration of the glory that was Athens. At his funeral, politicians, the fat and the tall, promised to build – at least that – the Athens Tram and give it his name. But who has ever believed a politician in a state of rhetorical exaltation? Voluptas post mortem nulla.