A century ago archaeologists began tentative exploration in western Crete, but in the intervening years no master has summoned up a Minoan center there to match anything like what Evans found at Knossos, the Italians at Phaistos, the French at Mallia or Nicholas Platon at Kato Zakros.

Homer’s ‘Crete of one hundred cities’, the earliest civilization to flourish on European soil, has seemed till now an exclusively central and eastern Cretan phenomenon. The Italians were the first to take up serious archaeological investigation west of Psiloritis (Mount Ida). In 1893 Gaetano de Sanctis and Luigi Savignoni ventured into the districts of Hania and Rethymnon, seen then as a wild region, but they located only classical, Hellenistic and Greco-Roman sites on the north coast, at Aptera, Diktynnaion, Polyrrhenia and Falasarna.

Even today in Hania (ancient Kydonia), Minoan enthusiasts see only unenticing digs through barbed wire, labelled ‘Greek-Swedish Excavations’, on a site sunk below street level on Kanevarou Street in the harbor promontory area of Kastelli.

In the Archaeological Museum, however, is a puzzling array of Minoan material. Conspicuous for size are pithoi dating back to Middle Minoan 18th-century BC days from a cemetery on Akrotiri and a ceramic bathtub from the same period, decorated with an octopus design and re-used as a coffin. It was dug up from a chamber tomb in 1983.

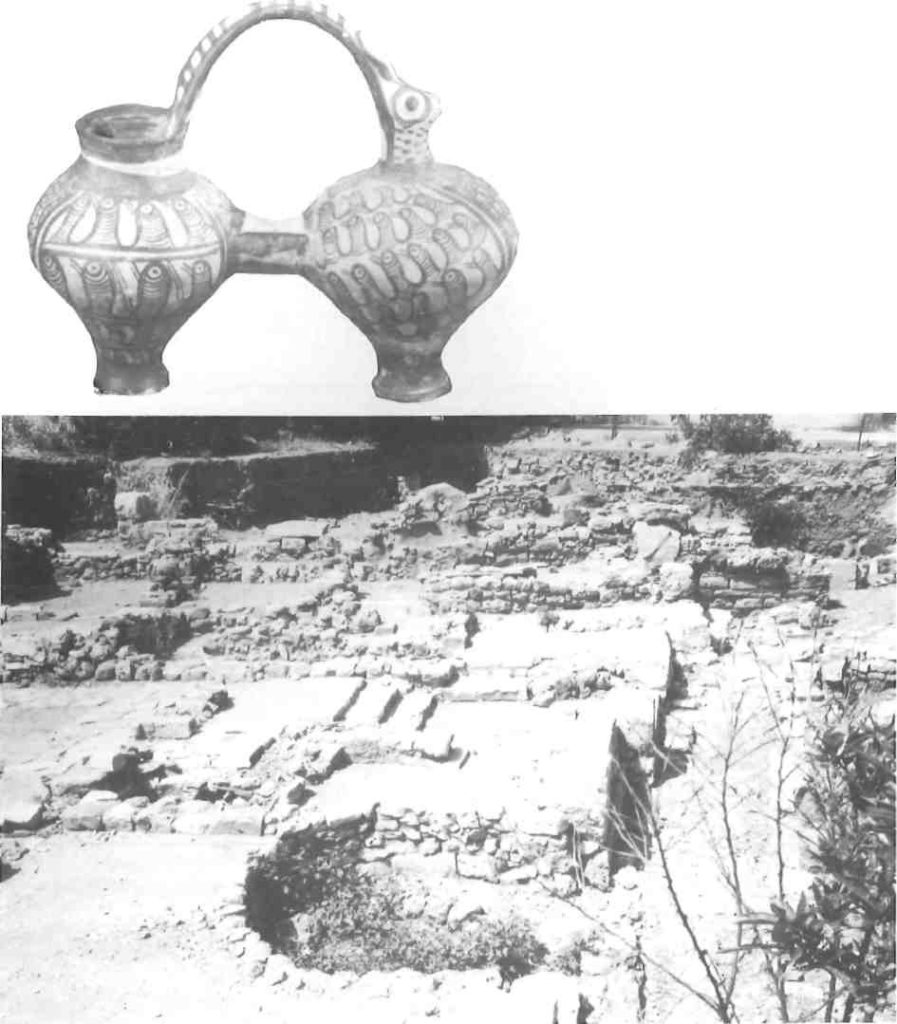

Appealing pottery includes a round box (pyxis) decorated with a lyre-player surrounded by birds and double axes, a globular flask and a pair of linked amphorae from a Late Minoan local workshop producing from the 15th to the 13th centuries. (Some of these pottery finds come from a tomb at Kalami south of Suda Bay.)

In one showcase small baked-clay tables and sealings are etched with the Linear A ideograms Minoans used for their vanished language. These show Kydonians were totting up their sheep and goats, olive oil, wine, figs and wheat with symbols denoting numbers up to one thousand as long ago as 3000 BC.

Several tablets and a vase inscription are in Linear B, the Minoan Linear A taken over by mainland Mycenaeans for their early form of Greek and hence decipherable.

Not much formation on Minoan Kydonia is generally available later than Homer. Hania Museum attendants are clearly tired of saying that nothing is published. Not a single postcard of an exhibit is for sale. Most museums at least run a card of a prehistoric pot, a votive idol or a poppy-sprinkled site: not here.

Tantalized by this glimpse of Minoan Kydonia at the Museum and puzzled over contemporary clouds of mystery wreathing the discoveries, I peered again at the Kastelli site one day last summer, marvelling that it supported evidence to show Hania as one of the oldest continuously inhabited towns on earth.

As luck would have it, the Swedish excavation residence was nearby and occupied by Dr Erik Hallager, who I learnt has been field director for the Swedish Institute team working under the general direction of the Greek Archaeological Service since 1969.

Hallager told how trial digging was done from 1964-5 by the Cretan, Dr Yiannis Tzedakis, ephor for western Crete of the prehistoric and classical department of the Ministry of Culture. He has trained under Spyridon Marinatos, excavator of the Minoan colony of Akrotiri, on Santorini.

Delighted with promising finds, Tzedakis sought partners from a foreign archaeological school in Athens.

The Swedish Institute took up the invitation, under its director, Dr Carl-Gustaf Styrenous. Hallager, a Dane, was among Scandinavian scholars then working at the Swedish Institute, joining the project in 1971.

Slow, painstaking digging has been required, as ten layers of habitation have been exposed. “It must be one of the most complicated excavations ever done,” he says. Systematic digging from 1969 till 1987 turned up two millennia of Minoan habitation, with earlier settlement back to at least 3400 BC known to lie deeper with Geometric, Venetian and modern Greek building above.

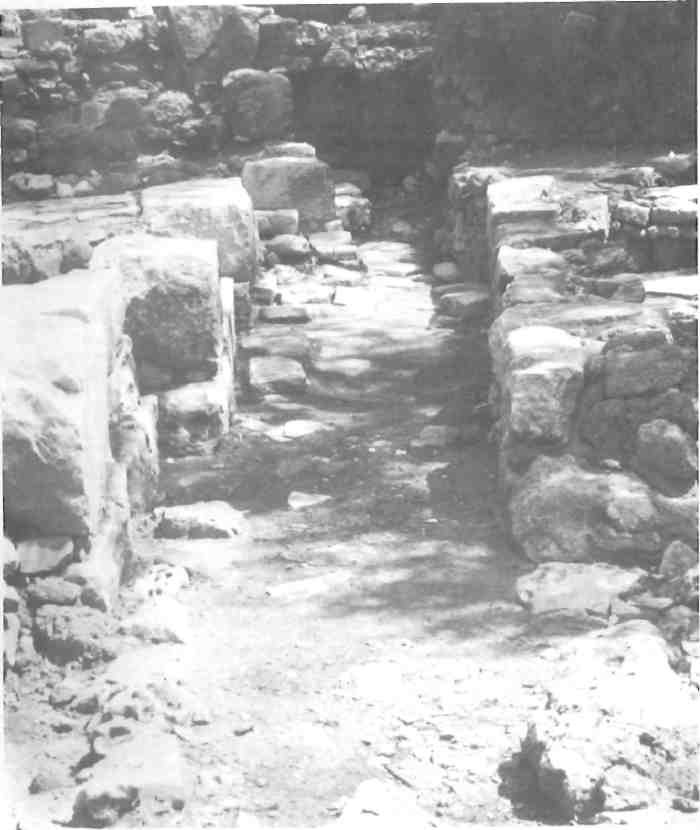

Clambering down into the excavations, Hallager brings the site to life. Four Minoan houses can be identified on two streets, with a small square. The layout, he comments, is more like that at Akrotiri than known Minoan towns on Crete.

The biggest house is 225 sq.m, apparently two or three-storeyed, the upper part of timber, foundations of stone. Crushed murex shell in flooring suggest Kydonians made the deep crimson dye by boiling molluscs.

The house appears to have 14 rooms, one being the typical Minoan main central hall with light-wells. Leading off it are several rooms, including a cult room, a storeroom, a kitchen and a room with a staircase, under which was a bathroom drain.

At the time of the catastrophic and general destruction of Minoan Crete in about 1450 this house was burnt down. Evidence shows almost immediate re-occupation in the form of squatter habitation. This went up in flames about 1375.

Soon afterwards, modified buildings were constructed, only to be destroyed in another conflagration about 1300. Minoans built on the spot for the last time about 1200, remaining in occupation for about 50 years. The fires meant excavation done through tons of charcoal. Diggers came up each day black as chimneysweeps, recalls Hallager.

Among finds in the cult room of the main house were decorated ceramic cups, vases, terracotta lamps, sealings, beads, amulets and clay corks. Some 40 clay loom weights and the charred remains of a wooden loom were found in the kitchen, which had a square hearth unknown in such a Minoan house elsewhere.

Four big pithoi, medium-sized clay storage jars (one containing two kilos of charred peas), vases and stirrup jars used for valuable oils, so clay analysis suggests, were found in the pantry. Some pottery is presumed to have stood on a wooden shelf which collapsed in a fire, judging by scattered pottery fragments.

A booming backroom industry in Crete since discovery of such fire-damaged Minoan remains has been the restoration of smashed pottery. Hania Museum’s Kostas Konstantakis, trained by Italian technicians at Phaistos, is one of Greece’s top pottery restorers, says Hallager.

Prize finds in the Kastelli house were many tablets inscribed with Linear A, suggesting an administrative center. And just outside the site, three complete Linear Β tablets were found lying on the floor of a house destroyed by fire in 1300.

Archaeologists, called in to rescue operation in 1990, checked out road-works where sewage pipes were being laid. “We’d been working for three months and on the last day but one – it always seems to be like that – we came to the remains of a room with these tablets,” says Hallager.

These are the only Linear Β tablets found in Crete outside Knossos. One thing they clear up is the dispute as to whether or not Dionysos was a Bronze Age deity. “One tablet mentions offerings of pots of honey at a shrine to Zeus and Dionysos, so it seems he must have been a god,” says Hallager.

The most striking find at this Kastelli site surfaced in 1983 in a rubbish dump used by Late Minoan II Kydonians after the first fire in 1450. Credit for spotting the matchbox-sized object goes to a site workman, Manolis Tsitsiridis, trained by Spyros Vassilakis who had worked at Knossos with Evans.

Round and chunky, reddish to dark brown and greyish black, the 3.2 by 3.1 cm find is a completely preserved seal impression on clay of a metal ring. “The intaglio is unusually deeply incised whereby all the motifs are presented not only in clear relief but also in perspective,” wrote Tzedakis and Hallager in a joint presentation at a symposium in Athens in 1984.

A powerful figure is depicted above a building complex on a rocky landscape by the sea. With bulging muscles and wasp waist, he wears typical Minoan dress: codpiece, kilt, belt, short boots and leggings. In an authoritative stance, he holds a spear, staff or javelin pointdown on the rooftop, symbolizing victory perhaps, as on similar Hittite, Syrian or Mesopotamian seals.

Religious significance is adduced as the figure stands between Minoan horns of consecration and has several ‘UFO’s around him. The figure has been compared to the Prince of the Lilies on the Knossos fresco, the prince of the Chieftain’s Cup from Aghia Triada and figures on other sealings like the Mother of the Mountain and the Epiphany ring from Knossos and several from Zakros.

However obvious the parallels, the Kydonia seal impression is a unique masterpiece of minor art. It is dated L Μ II because it was baked in a fire. One scholar has christened him Astyanax, as wanax may mean god or man. Minoan finds in Hania are not limited to Kastelli. Other Minoan remains lie exposed on sites cleared below street level round the neighborhood. In the adjacent Splantzia district, in Daskaloyianni Street, a rescue dig in 1989 turned up a Minoan lustral basin with painted decoration in the basement of a house now demolished.

Chamber tombs south of Hania’s law courts were excavated in 1959-61 by the late Nicholas Platon. In the suburb of Halepa and near the modern stadium pithoi from Middle Minoan days (about 2600-2000 BC) and rich pottery finds have been unearthed, says Tzedakis.

Chiefly frustrating archaeological curiosity in Hania is limited access to what lies below because of the intensively built-up nature of the area. Thebes poses the same problem, with the Mycenaean city of the seven gates, legendarily founded by Kadmos in the 14th century BC, lying under a leading Byzantine silk-manufacturing city and the modern town.

Both in Hania and Thebes, rescue digs during drain-laying and on building sites regularly turn up treasures, though it was the fortunes of war that laid bare the Kastelli site.

A Geometric and then a classical city succeeded the Minoan at Kydonia. Walls of classical masonry may be picked out around the harbor. Byzantine wall-building followed Roman occupation and a Christian settlement was destroyed like much else in Crete by Saracens led by Abu Hafs Omar after his expulsion from Spain and Alexandria.

Under Saracen rule, from 824 till 961, the small town, now known as Al Khania, was noted mainly for its cheese, says Haniot historian Anestis Makridakis who, as director of tourism from 1948-68, was known to utter the cri du coeur to archaeologists: find me a palace!”

After 243 years as part of the Byzantine Empire once again, Crete was purchased by the Republic of Venice for a thousand pieces of silver in 1204 from Boniface III of Montferrat, a ringleader of the Fourth Crusade which sacked and occupied Constantinople for over half a century.

By the early 14th century, a brilliant building program had began in Hania. The city became known as the ‘Venice of the Orient”.

German military authorities and undertaken by the German Archaeological Institute during the subsequent occupation. Digging was done by Cretan labor and, according to the account by Friedrich Matz published in 1951, any finds were supposedly handed to Greek authorities. To the scholar U. Jantzen, who did a wartime study of finds from Minoan tombs around Hania, goes credit for the first looking twice at the Kastelli bomb site.

One of the earliest Venetian buildings in Kastelli was the cathedral of Santa Maria, dating from 1320-66, with vaulted nave and soaring Gothic arches. Built on an east-west axis, foundations of part of the south wall cut into houses where Minoans had lived and worshipped 3000 years earlier.

William Lithgow, exploring Kastelli’s maze of steep streets, noted 97 palazzi and many courtyards surrounding the Duomo in 1632. After a two-month siege in 1645, Ottoman Turks captured Canea and later converted Santa Maria into a mosque. The place served for the worship of Allah till 1922 when 11,000 Muslim civilians went to Kernel’s new Turkey and 13,000 Orthodox Greeks came to Crete as penniless refugees in the population exchange.

The building had remained in good order, photographed by the visiting Italian Giuseppe Gerola in 1902, but in the poverty-stricken interwar years it was disused and neglected.

A gazosa (carbonated drink factory) was built diagonally in front of it. Our peephole view of the Minoan past is possible because in May, 1941, a Luftwaffe bomb fell on the factory and cathedral during the ten-day Battle of Crete, the last stand by Cretan and Allied forces against the German invasion of Greece. Only a sanctuary arch remained standing.

The first systematic excavations in western Crete were commissioned by ancient house walls and Late Minoan III sherds where the drink factory had been and the south-west corner of the cathedral had obtruded.

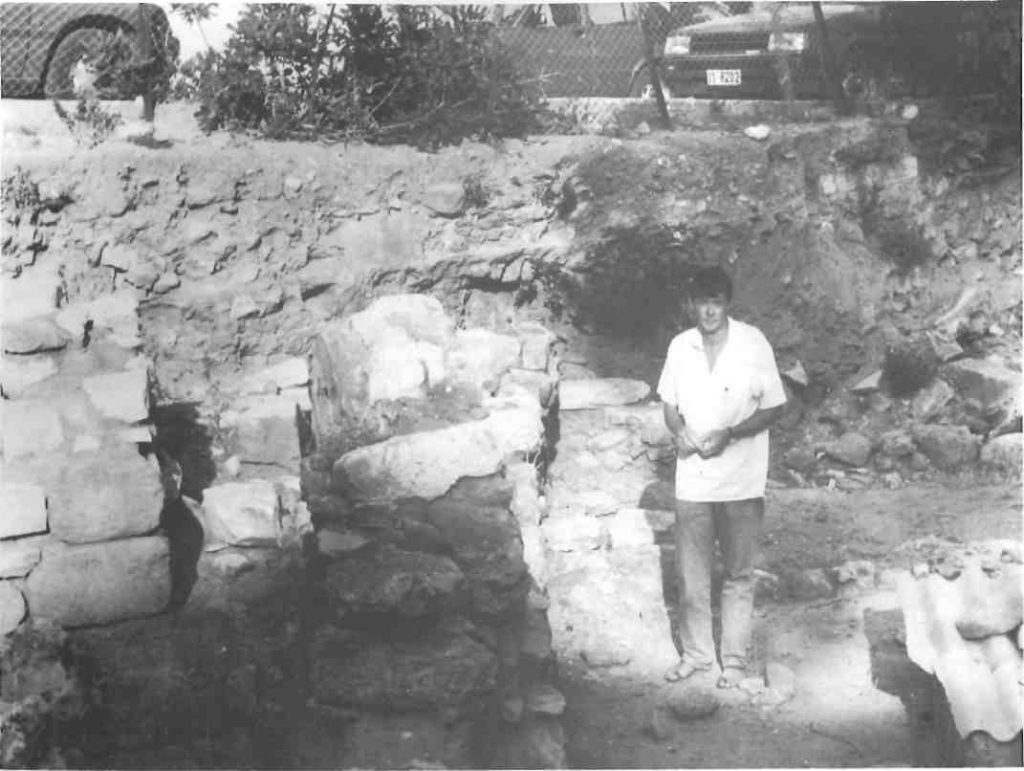

(Below) Minoan excavation viewed from the south. Steps lead up to the Minoan hall. The cult room, kitchen and storeroom, each containing many pottery finds, lie beyond. A gazosa (carbonated drink factory) covered the area till destroyed by a Battle of Crete bomb in 1941

‘The Minoan city must have covered the high ground of the Kastelli area immediately south of the harbor, on the east edge of which wartime destruction has exposed deep Minoan deposits,” Jantzen wrote.

The German account was reviewed in the periodical Gnomon in 1953 by Minoan archaeologist Sinclair Hood, director of the British School of Archaeology in Athens (BSA). Ten years later, in 1963, Hood received in his mail professionally done drawings of Middle Minoan I sherds from the Kastelli site. They were the work of British artist and amateur archaeologist John Craxton who had just moved to Hania and bought a rundown old Venetian house overlooking the harbor. “I heard of plans to build a church dedicated to Aghia Aikaterini on the site and felt sure the sherds I saw were Minoan,” Craxton recalls. “Nobody seemed to care much. I showed some sherds to the mayor who said they may have had historical interest, but were of no value. I then became accused of engaging in smuggling antiquities because I had the sherds in my possession.”

Hood confirmed the sherds were Minoan and consulted with a leading figure in Haniot affairs, Manousos Manousakis, who alerted th’e newly-appointed ephor, Tzedakis, of the need for a rescue excavation. Craxton relates being present on the occasion when Tzedakis raised the question of a Kastelli dig with Dr Stylianos Alexiou, then director of antiquities for Crete.

“Why?” he allegedly replied. “You’ll only dig holes. You won’t find anything.”

Within two years, Tzedakis’ trial dig was justified. Writing in the 1965 BSA annual, Hood declared: “At Hania there may have been a Minoan city rivalling in size and importance those of eastern Crete. Kydonia,” he surmised, “may have been the capital of the western part of Crete.”

A complete cross-section of the controversial final centuries of Minoan civilization from 1450 till 1150 has been brought to light in Kastelli, the only sites apart from Knossos with such a stratigraphy. Archaeologists are beginning to revise their ideas about Late. Minoan development in view of the findings.

The Linear Β finds show Mycenaeans were certainly on the scene. The absence of human remains in any of the charred buildings suggests the inhabitants either fled or were taken captive.

The curator at Knossos for the past two years, Dr Colin Macdonald, formerly with the Oxford archaeological scientific service, believes it is possible Kydonia was the only palatial center totally independent of Knossos after the 1450 destruction. “The important thing about Knossos and Kydonia is that they both carry on after that catastrophe and may now be recognized as the main administrative city in Crete.”

By that time, the Mycenaean take-over, sudden or gradual, had occurred. “The most convincing evidence for this is the existence of Linear B. Before 1450, Linear A was used to write one or more Minoan languages. After 1450, Linear Β was used for Mycenaean Greek; that is to say, Mycenaeans had taken over Linear A for their own language.”

For administrative purposes, a palace must have existed in Kydonia. “There’ll be a major building lying under present-day Hania,” says Macdonald. “Architecturally, most of it may have been destroyed, as Kydonia has been so continually inhabited. But certainly it will be there.”

Tzedakis and Hallager are models of scientific caution in interpreting their finds. They dash any popular hopes of immediate light being shed from Kydonia on the legend of the lost city of Atlantis which has sometimes been identified with Minoan Crete.

Furthermore, recent scientific evidence suggests the first destructive Minoan fires were not simultaneous with the Santorini eruption. Traditionally put at about 1450, the eruption, new evidence shows, could have occurred at least a century earlier.

Both back Evans’ belief that human agency, not natural catastrophe, caused the Minoan palace destructions, partly because not all were similarly affected. Tzedakis postulates local uprisings against mainland authority. Mycenaeans may have become so assimilated into Minoan society they lost any allegiance to the mainland. The extreme scarcity of Mycenaean-style pottery in Crete shows that Minoan culture continued to prevail.

So a century or so after arriving in Crete, Minoanized Mycenaeans rose in revolt, just as 150 years after arriving, Venetian colonists in Crete rose in revolt against Venetian authority in the St Titus Revolt at Candia (Irakleion) in 1363-6.

Minoan civilization ended about 1150-1130 at the time of great migrations when Dorians swept down from the north and, more importantly, when trading opportunities with the east declined as the great Hittite and Egyptian empires decayed.

Minoan Crete had prospered by exporting oil, wine, woollen cloth, resin from cedars for balsaming the Egyptian dead, and honey. Widely scattered Kydonian workshop pottery after 1350 shows the extent of Kydonia’s share in this trading – as far west as Sardinia, at Taranto, up to the east in Cyprus, and all over mainland Greece and the Aegean islands.

A seven-volume account of the 17 years’ digging on the Kastelli excavation is planned. The first is being written by Hallager and Hania ephnelitria (assistant director) Maria Vlazaki, a Geometric period specialist. This will cover the top layers from eighth-century BC Late Geometric days onwards.

The important account of the Minoan findings is being prepared by Tzedakis, as general director of the excavation, and Hallager, as their professional commitments allow.

Tzedakis left Hania in 1982 to become director of the prehistoric and classical antiquities service of the Greek Ministry of Culture. In 1990 he moved to the palaeoanthropology and speleological service.

Based at Aarhus University in northern Denmark, Hallager edits a magazine, Sphinx, on the Mediterranean heritage and with his archaeologist wife spends a working season in Hania each year.