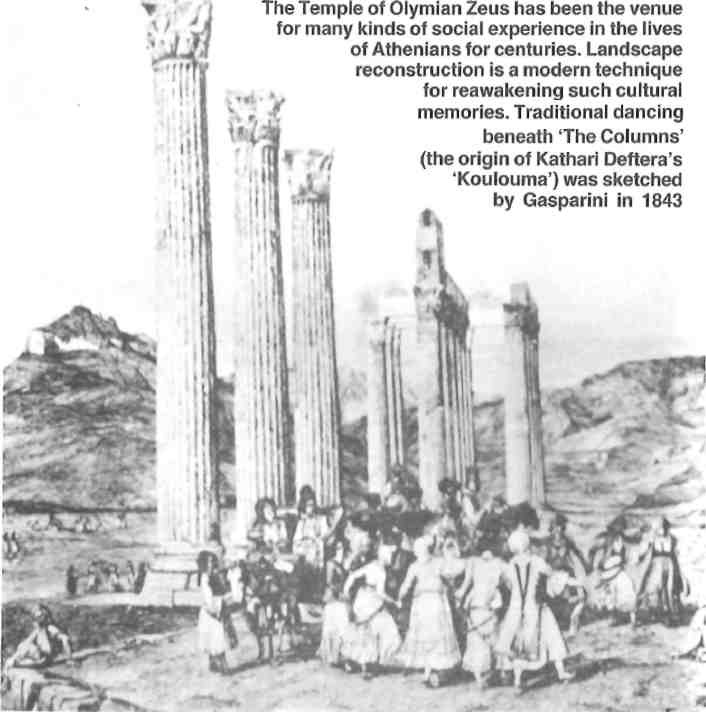

There are times in our experience of a place, on returning after a long absence, when we no longer feel the connection we once had with it. Time can permanently change those aspects which made it so familiar. If we could go back and trace the experiences which shaped it, we would better understand the landscape and learn new ways of connecting to it. The modern city of Athens, like white-leafed ivy, has stopped just shy of claiming its historic sites. It is busily climbing the mountains which surround it on three sides. This is a testament to our ability as people to live either in harmony or in discord with past culture and the remnants it has left to us. Landscape reconstruction is one way of re-establishing those connections, re-learning how we see our immediate environment.

Landscape reconstruction is the editing of a contemporary viewshed to reveal its historic or past visibilia. It is the visual editing of an image, not an actual physical reconstruction. The term viewshed is defined as a selected area of the landscape visible from a given viewpoint. Visibilia are the physical elements that are seen; the phenomena. We define landscape as a physical setting which contains human activity, rooted in the use of the place often, as in Athens, over great periods of time. Any effort to understand the landscape as place must be guided by reverence and humility towards it with a sense of wonder about its hidden personality.

Computer-generated visual simulations are a powerful media for documenting and communicating photo-realistic reconstructions of a landscape. When we see a landscape through a series of identical viewsheds, we strengthen our cognitive connection to the specific physical elements within that space. Through careful reconstruction of those elements, a new image emerges which portrays the same setting at a different period of culture and human activity. This process helps us uncover the living memory of the place, the continuum of its experience through time. It compels us to understand how it was put together by taking it apart and replacing its elements with documented information and sheer imagination.

In 1870 the Temple of Zeus still lay outside of the growing (cont.)

In dealing with our environment, we try to direct change in a manner that respects the human, natural and cultural resources of a place. We recognize that each place has unique elements which separate it from any other, and that it is this uniqueness we initially respond to. The difficulty of understanding a place as a whole – its physical structure, visual features and their impact – is even greater in places where physical fragments of the past culture coexist with a multitude of expressions in contemporary culture. Available visual records offer only a limited overview and understanding of a place. The majority of these records show the documentation of historic structures within their immediate site. The landscape in a broader context is rarely portrayed. The use of the land, the territory linked with’ the structure, the fields, the forests and the rivers are inseparable elements of the place.

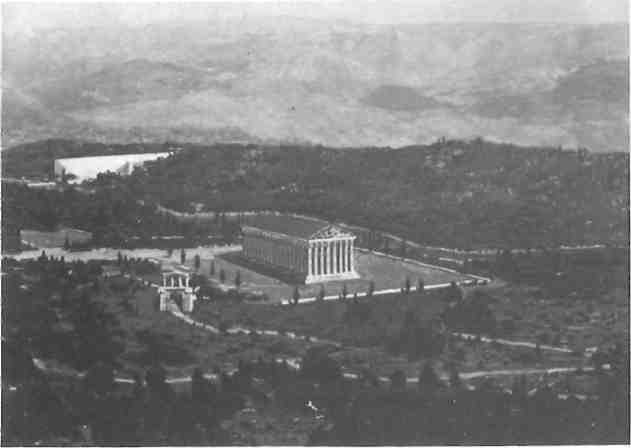

In Imperial times the sanctuary lay just inside the city walls. The Stadium beyond had been rebuilt in marble to host the AD 144 (cont.)

The primary objective of a recent project was to develop a set of images to communicate to officials and the general public how the character of the landscape contained in the selected view has changed over time. Through the reinterpretation of the historic space, the threat to its integrity by contemporary development can be managed through more effective planning and design controls.

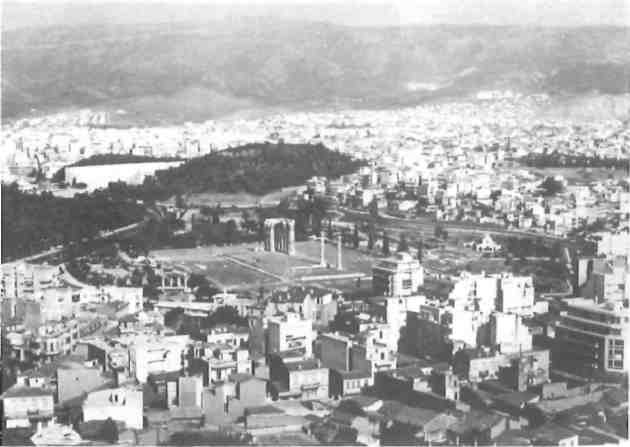

Let us take the view from the north-eastern side of the Acropolis. Views from this particular location are photo-graphed by visitors because they offer good vantage points of the Temple of Olympian Zeus, its relation to the Acropolis and the modern city, and finally the city’s expansion up the slopes of Mount Hymettus.

The precinct of the Temple of Zeus extends between the Acropolis and the river Ilissus to the southeast. The ancient river bed has been enclosed and paved over to serve as a major transportation artery and sewer trunk line. This area, together with the Acropolis, was part of Athens even at the time of Theseus. The land adjacent to the river then had lush vegetation and an abundance of fresh water from the Kalliroe Spring. Several important sanctuaries were built in the area, including the Olympeion, the Pytheion, and the sanctuar^ of Aphrodite in its gardens.

The existing temple was envisioned as an enormous Doric structure in 535 BC by the tyrant Peisistratus, but it was only completed by the Emperor Hadrian 650 years later. In its final form it was in the Corinthian order with a double row of columns. It was surrounded by a large rectangular space, and was much taller and larger than the Parthenon. In addition to the temple, sanctuaries and excavations revealed the remains of many other buildings, including two of the largest gymnasiums of ancient Athens.

A 3D wire frame model, assembled in Auto CAD, was inserted into the scanned image of the selected view. Next, the composite image was rendered using paint software to reconstruct the Temple, ensuring compatibility with color, light, shadows, and texture. Beginning with the existing landscape, two historic periods were simulated. Each image was edited based on historic research of written and visual records, including archaeological documents, narrative descriptions, as well as contemporary folklore and archival photographs.

The 1870 AD image shows compact urban settlement extending out from the Acropolis. Unpaved paths lead to the Temple, the cultivated fields and the Ilissus River. Clusters of homes dotted the hillslopes easf of the river. Their architecture replicated traditional buildings found in the Aegean islands. The ancient Stadium, where after restoration the first modern Olympic games would be held 20 years later, had long been abandoned, covered with eroded soil and debris. The area extending to the foothills of Mt Hymettus was undeveloped, used for grazing and scattered with farms. Most of it had no tree cover as a result of successive cutting of deciduous forests.

The archaeological remains had withstood the ravages of several invasions and wars to be left in the shadows of a growing modern city. The landscape exhibits a clear transition between the countryside and the urban area. This area served as a gateway between the two and from the sea into Athens. In a semi-arid climate, the presence of the water and fertile lowlands offered an area of relief for Sunday excursions, gatherings, and folklore.

The Imperial Roman image was chosen based on available information showing the spatial configuration of Athens and its environs at that time. The map for the same period highlights the main physical features. This image shows a representation of the landscape as it probably looked. The Stadium, which was then in active use, was contained by the Ilissus and the wooded hillsides. The Ilissus was free flowing, flanked by lush bottom-lands with plane trees, fruit trees, and evergreens, The predominant types of vegetation were the Aleppo pine and shrub clusters. Networks of footpaths connected the temple with the built-up area around the Acropolis.

In the four years we have been producing computer images, we have found that photo-realistic pictures generate enthusiasm unparalleled by hand-drawn renderings. This allows for a direct comparison between the past and present character of the landscape. The images are also more readily accepted due to the lack of abstract interpretation on the part of the viewer.

During the process of landscape reconstruction, the production of the simulations draws the viewer into the image, Seeing is expanded by using computer software to manipulate and edit elements within the image. The gradual reconstruction of a place reveals meaning simply by our involvement with its past. By transforming its character, we explore, learn, and eventually make a closer connection with what we see. Educating contemporary inhabitants about the persona of their space, as it has been transformed by past culture, is essential in forming their own sense of significance within that space. Or, in some cases, their insignificance.