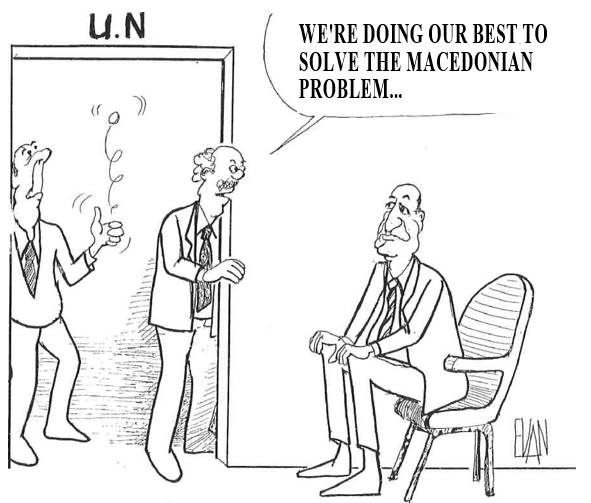

While the mood in Greece fluctuates almost every day in regards to the outcome of its tussle with Skopje over the name ‘Macedonia’, most observers are coming to the conclusion that the feud is likely to carry on far longer than originally anticipated. Irrespective of the outcome of the developments before the United Nations and the European Community, it is not international bodies in the final analysis that can impose a final solution but bilateral negotiations between the two feuding sides to find a compromise.

The reason for this, according to both Greek officials and western diplomats, is that Greece is likely to react harshly if it fails to prevent the former Yugoslav republic’s recognition at the UN under the name ‘Macedonia’. Under pressure from the public opinion it has stirred up, and now angered over what it sees as ‘betrayal’ from its western allies, Athens is likely to opt for its only remaining choice: to close its borders with Skopje-Macedonia, thereby rendering even more difficult the republic’s economic survival in the hope of compelling it to compromise.

Another threat Athens may carry out, this time in anger over the EC’s failure to follow through with the Lisbon Declaration last June to recognize the Republic only if it did not include the word ‘Macedonia’, is to abandon solidarity with the Community over the Yugoslav crisis. In its worse form, this might mean increasing indirect support to Serbia, thus making it harder for the West to coordinate pressure on Belgrade.

These ‘worst-case scenarios’ over Greek reactions have been fleshed out as it becomes increasingly difficult for Athens to push through its case. Greece’s arguments against its neighbor’s use of the name ‘Macedonia’, namely that historically and culturally it belongs to Greece and that its use implies territorial claims against its northern regions, does not appear drastic enough to convince the rest of the international community. As far as the EC is concerned, the question of the name is secondary. Priority is given to recognition of the republic so that it can receive international aid and stabilize its regime. Stability, they argue, is paramount so as to prevent spreading the war into the southern Balkans.

Athens, however, insists that the opposite is the case, claiming it was proved right in cautioning the world not to proceed with a hasty break-up of Yugoslavia and recognition of its constituent republics, as this would only provoke war on a wide scale. It warns that the same could happen with Skopje-Macedonia. Firstly, because it is made up of two equalsized Slavic and Albanian populations which dislike and distrust each other intensely and are bound to clash sooner or later. Partition of the republic and the absorption of part of it by Albania is feared by many. Secondly, adds Athens, the retaliatory measures Greece will take will make the republic’s survival extremely difficult.

What does Greece mean by this? What can or will it do in the case that it loses the battle at the UN, that the former Yugoslav republic is accepted as a member under the name of ‘Macedonia’, and that the EC members then also proceed with bilateral recognition?

Actually, it can create considerable difficulties, so long as it has the diplomatic stamina to persevere even at the risk of making itself more unpopular internationally, and suffering considerable tourism and economic losses. Such losses come as a result of interrupting ‘motoring and overland’ tourism from western and central Europe. The only viable sea-and-land route will be through Italy, which is already a far more common route for Greek and western travellers today. A drop in south-north overland trade is in the cards since Greek and TIR trucks will be compelled to take longer routes through Bulgaria. The tourism revenue from former Yugoslavia (like day-shopping in Thessaloniki) will also stop completely.

On the other hand, a closure of Greece’s borders with Skopje-Macedonia would cause far greater hardships for the small republic. It would make it more difficult to move its trade southward, unless it goes through the far longer and costlier routes of Bulgaria and Turkey. Similarly, it would mean that it cannot have access to the sea through the port of Thessaloniki, which is the key point for imports and exports and, above all, for its oil supply. Albania to its west and Bulgaria to its east are poor substitutes, while to the north lies Albanian-populated Kossovo and a hostile Serbia.

Furthermore, within the small republic lies the potentially explosive Albanian element, which in numbers is just as great as the Slavs. The Albanians do not want recognition under the name of ‘Macedonia’ unless the international community meets their own demands for greater autonomy as a ‘constituent national element’. Since these are not being met to the extent insisted on by the Albanians, recognition is likely to provoke more reactions from them. This discontent is in turn likely to be aggravated further by the economic malaise brought on if Greece blockades the border. Greece, besides, may well lend its support to the Albanians of Skopje as they put pressure on the government.

President Gligorov’s government argues the contrary; namely, that recognition will bring stability, greater domestic tranquillity, and economic support from abroad. For example, non-recognition has meant so far that the republic cannot negotiate loans with foreign governments, banks and other financial institutions.

Greece counters that really meaningful aid can only come from the European Community, and that such aid can be vetoed by Athens. As for American aid, Greece also argues that it can again cause considerable difficulties through its powerful Greek-American lobby. In all cases, Athens points out, it is in the republic’s interest to compromise on the name, since that is Greece’s only demand. Athens has no territorial or other claims whatsoever. The government keeps on repeating that it is ready to recognize the republic and guarantee the inviolability of its borders as soon as it abandons international use of the name. By this it means that it accepts that the republic call itself ‘Macedonia’ domestically, much in the way that many other countries have dual names, including Greece (Hellas at home and Greece internationally).

Compromise, indeed, may well be the final outcome as the two sides continue to injure each other in this drawn-out diplomatic and economic tug-of-war. For whatever the UN and the European Community decide, international practice shows that the decisions of international forums are mainly of moral value and seldom of a practical or ‘enforced’ nature. Whenever either side in a dispute chooses to ignore international rulings – as with the Israeli-Arab conflict, Turkey and Cyprus, and perhaps soon Greece and Skopje – then solutions can only lie in bilateral negotiations.

In such a case, both countries will have to come to their senses and compromise over the name, to their mutual advantage. After a bit of pride-swallowing on either side, the solution can only lie in a mixed name, of the sort that have been discussed for many months now.

Specifically, a name which allows Skopje part-usage of the word ‘Macedonia’, but with a prefix which differentiates it geographically from Greek Macedonia. Something like North or West Macedonia or, even better, ‘Vardar Macedonia’. If the political leadership and the public in both countries are mature and responsible, the matter could then be put to rest and the area once again become the vital bridge of southeastern European trade and tourism that it used to be.