In every generation there are creative spirits who quit city life for the woods and the wilds, or in Greece for an island, to cultivate their talents. From Euripides going off to compose in a cave on Salamis in classical times to the late poet Nikos Vrettakos joining the eagles in the high-placed villages of Mount Taygetus in our own day, some souls need peace, quiet, the simple life and pure oxygen to render to the Muse her due.

Keeping body and soul together far from the marketplace can be a problem of course, and artist and spouse may need to learn to put up with a degree of material deprivation.

Like fellow-villagers, sculptor David Kennedy and Maya, his wife, still think electricity wonderful, since it came less than ten years ago. Water is precious too and cistern-stored rainwater conserved more jealously than the new season’s wine.

Once a week they go down to the small port of Perdika to buy well-water for trees, shrubs and plants on rock-walled terraces that archaeologists say date back to Paleolithic times.

Oral culture survives in hardy village families who pasture goats on the volcanic heights above the chapel and cemetery near their homes. From that vantage spot, the eye sees east to Sounion, west to Peloponnesian Arachnaion rising 1200 metres between Epidaurus and Mycenae. Acrocorinth juts up northwest beyond the humps of Salamis and the grand blue contours of the Methana peninsula soar into the south¬western sky.

The absolute silence of Sfentouri is ominously heavy to a citydweller straight off a ferry from Piraeus.

“Silence is a problem,” says Kennedy, gravely. “It means you mind noise so much more: a helicopter seems a monstrous intrusion and motorbikes roaring up the hill in summer can be unbearable.”

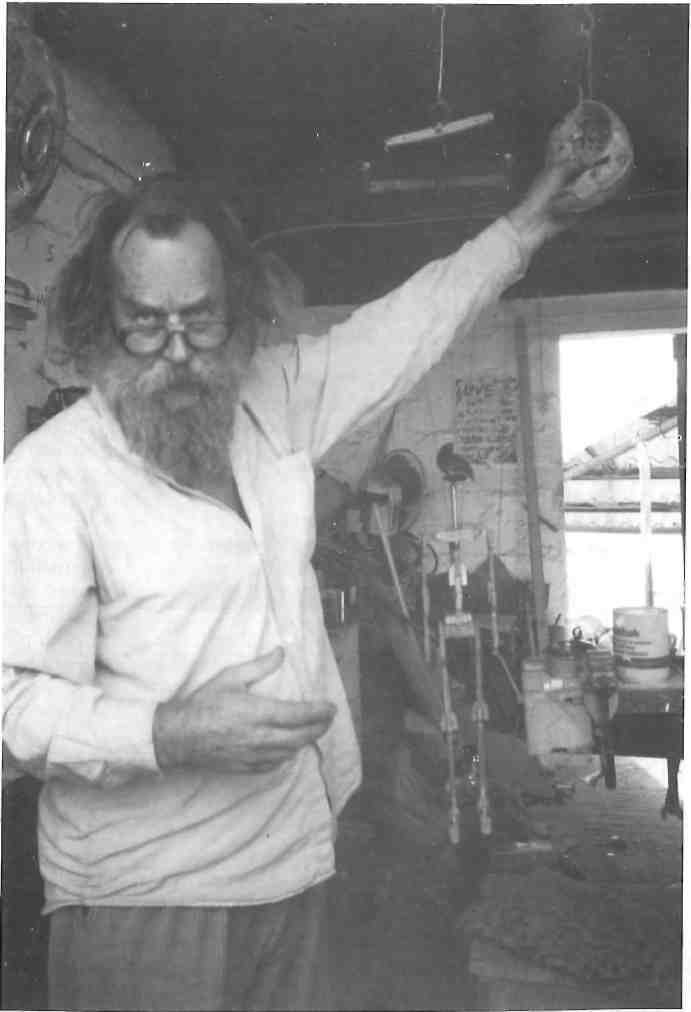

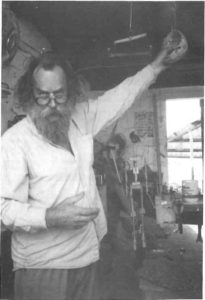

To concentrate on sculpture (and to distance himself from military dictatorship), he moved to Aegina in 1970. A selection of his Hephestian toils may be seen at two exhibitions in Athens early this year, his first in the city since 1974. Recent works are in metal.

“Bronze, if you like, but the word means any alloy: some are brass, copper and zinc, others copper and lead.”

Dozens of figures stand on shelves, and ledges and in nooks of the house.

A nude cellist is a favorite subject, from a model who played Bach for hours. The human form is the ultimate in beauty, he believes. As a man, preferring the female, “more interesting, anyway, narrowing and broadening, the male, in comparison, a plain slab.”

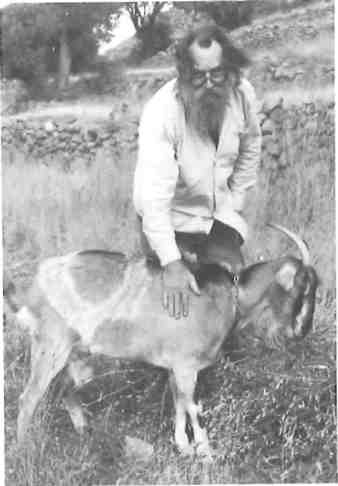

Many figures show a beloved 14-year-old nanny goat, childless after many miscarriages, called Niobe after the woman turned to stone, weeping forever for her children killed by the gods in spite. Kennedy takes water and olive shoots at noon to her on the rocky terraces.

Among the many life models around him, cats and cockerels roaming about and the odd scops owl also serve as subjects.

As a supplement to sculpture, he paints blue nudes of Sophia, his current model, and Sfentouri landscapes, using powder paints mixed with polymer (acrylic) on cheap cotton fabric or old sheets stretched on frames to cut costs.

Mask-making is a lighter genre, “Sort of, not really sculpture: it’s fun.”

Papier-mache masks with eyes that roll and mouths that open hang on walls like cuckoo clocks, ready for action at a touch. Peopling the house are Zeus, the Cyclops, Heracles, Pericles, a mythological faun, and a goat-headed bull (an aixotaur, he suggests, to use an archaic word for goat).

David Kennedy has branched out into marionettes in the last two years, life-size wooden or papier-mache fi-gures. An interim creation is a standing marionette set piece, a punk trio, inspired by his son, Jason, and co-musicians, who performs realistically when activated.

The cast of marionettes hanging by the long dining table grows as new figures are made to order for Vassilis Vassilakis, an ex-Athens Art Theatre actor turned painter, who is devising scenarios for shows. He rehearses movements with the intricately stringed figures for hours a day, working with his wife, his model Sophia, who is a teacher, on script development.

Kennedy marionettes were on exhibition at the Cultural Centre of the Municipality of Athens last December, put on by the Union of International Marionettists (UNIMA). Vassilakis performances are to be seen as part of Kennedy’s Spanish Institute exhibition in February.

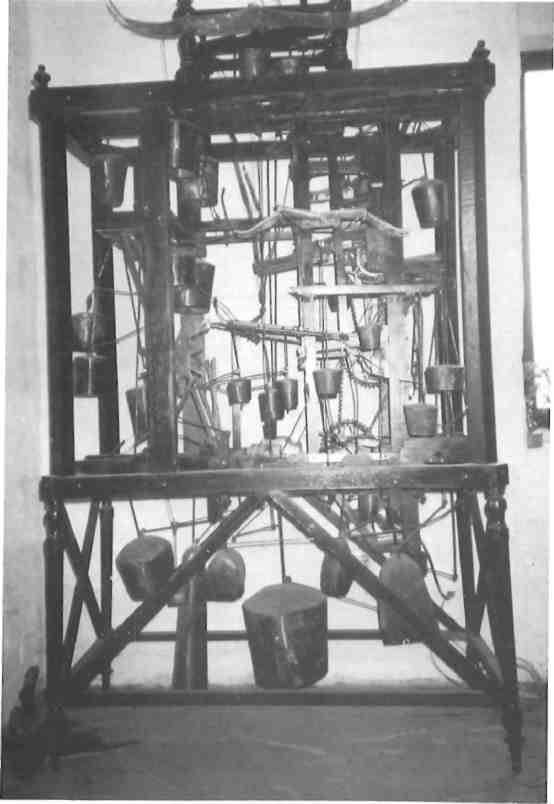

In a related genre are several large jeux d’esprits around the house, best described perhaps as a Tinguely or W. Heath Robinson sort of contraption.

In a corner of the main room is a wardrobe-sized construction inspired by a flock of sheep: myriad sheep bells of different pitches, cast in the Kennedy foundry, are hung in a harmoniously arranged hierarchy of frameworks, and may be made to jangle symphonically.

A construction inspired by the brike stands between doors going out to the balcony whose arches frame dazzling vistas over the sea to the Peloponnese. Among a variety of hinged metal pul-leys and pans, brikes are set at all conceivable angles. Cranked into ac-tion, the contraption shatters the quiet with a metallic din like a team of cooks summoning diners by beating spoons on pots.

Slung like an oldtime clothes horse from the beamed ceiling is a third sizeable kinetic device labelled “a new improved engine of gastronomic delights,” once part of the decor of a restaurant in Pasalimani run by Kennedy’s elder son, Garth.

In his main work, Kennedy represents generally recognizable subjects, as he believes that surrealism is about ideas, which are therefore more appropriate to prose and poetry than painting or sculpture, which deal with surfaces:

“They need a subject, any subject: you can have a great picture of a tin can no less than a gold crown.”

His models of excellence taken from Greek art go back to Bronze Age Cycladic. The third millennium seated harpist – the Parian marble figurine of some pre-Homeric rhapsodist, seems to him an unsurpassed piece of sculpture. A fine replica of it fills the room.

“It has a magic: people could not keep their eyes off it… Religious feeling is needed for such transcendent art, I am afraid: you don’t do such work unless you believe, and it’s got to be passionate belief; at least the things I think are greatest happened that way.”

If inspiration for his cellist figures may be traced back to the ancient Aegean world, precepts for his daily work come from the living, like the 83-year-old Christos Kapralos, who has worked from Plakakia in Aegina for 30 years.

“I take a few pieces to him once a year, not oftener, as he has so many visitors. He picked a piece up and stroked it. Words couldn’t have said more. He says simple things: ‘Look closely, then from afar, then from the middle. Look harder.’ That’s all it’s about really, understanding what you see.”

He quotes Kapralos:

“Good work comes only from much work.” So, monk-like, he is up each day before dawn, ahead of his crowing cocks. Workshop, studio and tower study let in ample light but no views.

As he has contrived surroundings down to important details, so he relishes the chores at every stage of the sculpture process.

The figures he models first in wax, a mixture of bees’ and paraffin wax with colophony (refined pine resin), which he concocts on a stove, making sheets by pouring the warm mixture into the surface of a broad shallow pan of water, where it spreads evenly to cool and harden.

Finished pieces get a few wax rods stuck on them, giving a Martian-like appearance, then are enclosed in a sheet of metal. The space around the work in its cylinder is filled with plaster, soft, fine gypsum mixed with brick or ceramic tile dust.

When enough work has accumulated, the day comes for lighting the kiln: when gently fired, the wax figures buried in the solidified plaster melt, running from the plaster cast through channels left by the rods. Perfect impressions of the modelled figures are left inside the gypsum waiting to be filled with molten metal poured in through a duct.

Kennedy sorts through his scrap metal, from old typewriters to a brass boat propeller, to fill up the Spanish crucible made from clay and graphite. No stage of the process is more serious, as a temperature of 1300 degrees Celsius has to be reached for the metals to melt.

“Most sculptors send their work to a foundry for casting. I know of only two others in Greece who do their own. You need space, for one thing. And it’s very frightening, a skilled craft, dangerous, hot, heavy work. But I couldn’t afford foundry costs when I was beginning: a small figure would be up to 80,000 drachmas. Anyhow, I prefer to do my own, though Greek foundries are good: other European countries send work here for casting.”

Electricity now powers the fan acting as bellows to make an inferno of the coke fire under the crucible, lowered onto a grate in a cavity of the concrete balcony abutting his work¬shop. Till the mid 1980s he pedalled a bicycle furiously for hours to drive the fan.

The weight of the pouring equip-ment necessitates an assistant. Both men wear firemen’s trousers (his ordin-ary ones caught fire once from the heat of the molten metal), asbestos gloves and dark glasses.

“Every movement is choreographed precisely. It’s like a surgical operation. The molten metal hardens so quickly, there’s only two or three minutes for the whole pour. Not a word is said, because of the risk of distraction. Any spectators must keep quiet, too.”

A plethora of influences has shaped his life, since birth in 1931 in Padding-ton where his father, married to an Englishwoman, went into general practice after doing medicine at Guy’s Hospital, thanks to family means from a string of pubs in colonial New Zealand.

Sent to English public schools for ten years, he hated every minute and still has nightmares that it is his last day at home and he has to go back to school tomorrow.

In 1948 he sailed with his family to Wellington, where he read modern languages at Victoria University, began studying architecture in Auckland, then switched to painting in adult education art classes.

Marrying a fellow student, he set up house in the forested hills north of the city, painting by day, working by night on the morning paper, rising from copyholder to reporter and sub-editor. He left to drive a forklift truck and bulldozer at a brick works with better pay for half the hours.

As an artist-journalist he” adventured to the South Pole on an Operation Deepfreeze ice breaker to observe and draw Antarctica wildlife and was featured on a magazine cover chatting to penguins and seals.

His commercial art work ranged from a series on old city pubs to mural painting for restaurants, among them the Timos run by an expatriate Greek, Tim Devliotis. As Heinrich Schliemann, discoverer of Troy, fell under the spell of Homer recited by a drunken sailor, Kennedy was entranced by the eloquent restaurateur’s sagas of life in Greece.

“He told me wonderful things about Greece – and lit a fire.”

In September 1963, with wife and two children, he sailed to England, bought a truck, converted it into a mobile home and drove to Greece.

“Nothing was like Devliotis said, but it didn’t matter. What followed were the richest years of my life.”

He lived in the Plaka, charmed by the neighborliness, the people from villages, craftsmen at work, street cries, musicians like the fiddler with a blue wig going round the tavernas.

“Bars and cabarets opened. Pimps appeared. Then came the Colonels’ coup.”

With his wife and children back in New Zealand, he walked all over Epir-os in 1969-70, drawn to the region by its feeling of isolation, but while visiting a friend, the poet Katerina Angelaki-Rooke on Aegina, he chose the island as handier for sculpture supplies.

When he married Maya in 1983 he had built the house among terraces of olives at Sfentouri. In the same year he exhibited in Italy, then in 1985 in Auckland.

Two earlier exhibitions at the British Council in Athens included works in welded steel and carved wood (1968) and hammered sheet bronze goats, cats and owls (1974). As a result, a flight of doves was bought for a plateia in Crete and a kinetic water sculpture commissioned by an American for a summer house on Skiathos.

The trip necessitated to take the work by truck from Aegina in 1984 was his last time off the island. “If you have what you want, why move? I know a woman in an inland village who has been to Aegina town only four times in her life.”

He broke seven years’ silence last August with an exhibition at the Markello Tower in Aegina jointly with the painter Nektarios Kondovrakis.

Among winter jobs was making scaled-down furniture – chairs, table, a bed, a flight of stairs, a ram – from an old larch chest-of-drawers for the marionette shows, while discoursing on the origins of 18th-century French marionette theatre, English Punch and Judy shows, the Commedia dell’ Arte and the Greek Karaghiozi shadow puppet theatre in the East.

He also had to make selections from 300 or so sculptures and round 100 paintings for his show at Ersi’s Gallery in Kolonaki this April.