A passing visitor to Athens might be forgiven for thinking that the concept of a park is foreign to Greek culture so devoid of green does the capital appear to be. But closer inspection reveals that at times Athens did at least attempt to make some provision for the traditional Sunday afternoon taking of the air, and the inner city municipalities today seem to be becoming more aware of the need to shoe-horn a few more recreational facilities amid the concrete.

The combination of a warm autumn and an eager child provided me with the opportunity to root out the green oases beneath the cement fagade. Armed with push-chair and a bag of tricks (including stale bread for any deserving ducks we might run across) we headed for the traditional parks and gardens of Athens.

First stop was, of course, the National Gardens. Formerly the Royal Gardens, its name was changed when it was first opened to the public in 1927. It was designed at the same time as the Royal Palace (now the Parliament building) by German horticulturist Friedrich Schmidt, under the auspices of Queen Amalia who pined for the forests of Oldenburg amid the heat, dust and rocks of old Athens. Landscaping and planting in the English style with trees, shrubs and plants from all over Greece and the world took place between 1839 and 1860, and, in fact, many of the 7000 trees today, 75 percent evergreen, are the original ones. The park covers an area of 158,000 square metres, comprising such a maze of 7000 metres of walkways, one imagines that even the park keepers must get lost from time to time.

The nice thing about the National Gardens is that around every corner there lurks a surprise, something you had always missed before. Among the leafy paths, lily ponds and lawns, you may happen upon the busts of poets Solomos, Valaoritis and Jean Moreas, Count John Capodistria, provisional president of modem Greece at its foundation, or Swiss banker and philhellene Jean-Gabriele Eynard.

You may come across the children’s library (though surely not by following the somewhat erratic signposts!), an ivy-covered fairytale cottage in which children between the ages of 5 and 14 can sit and read, draw or play. It is not a lending library, however. Nearby are the remains of some Roman baths, with large geometric mosaics. There are also a small botanical museum (which is almost always shut), a Roman plaque now bearing an inscription of St Paul’s speech to the Athenians, a reasonable children’s playground (Georgie gave it a 7 out of 10), a slightly dingy kafeneion next to Irodou Attikou, the best duck pond in Athens and a forlorn collection of birds and animals.

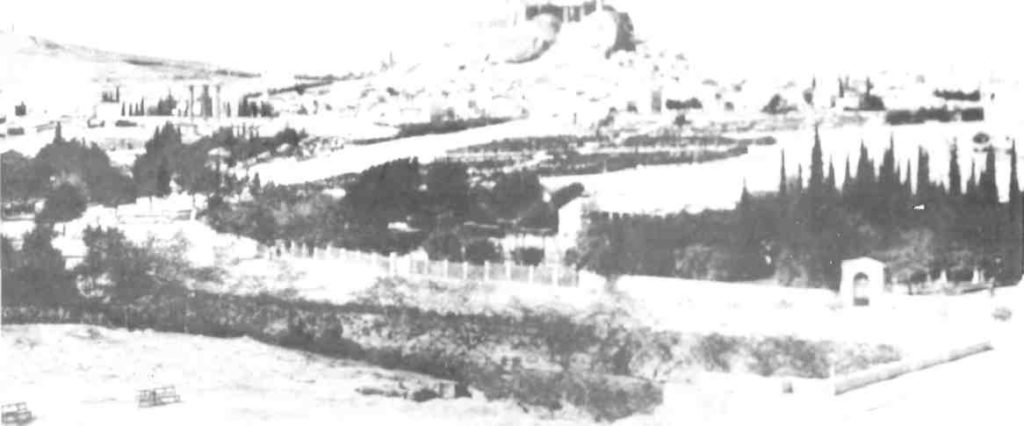

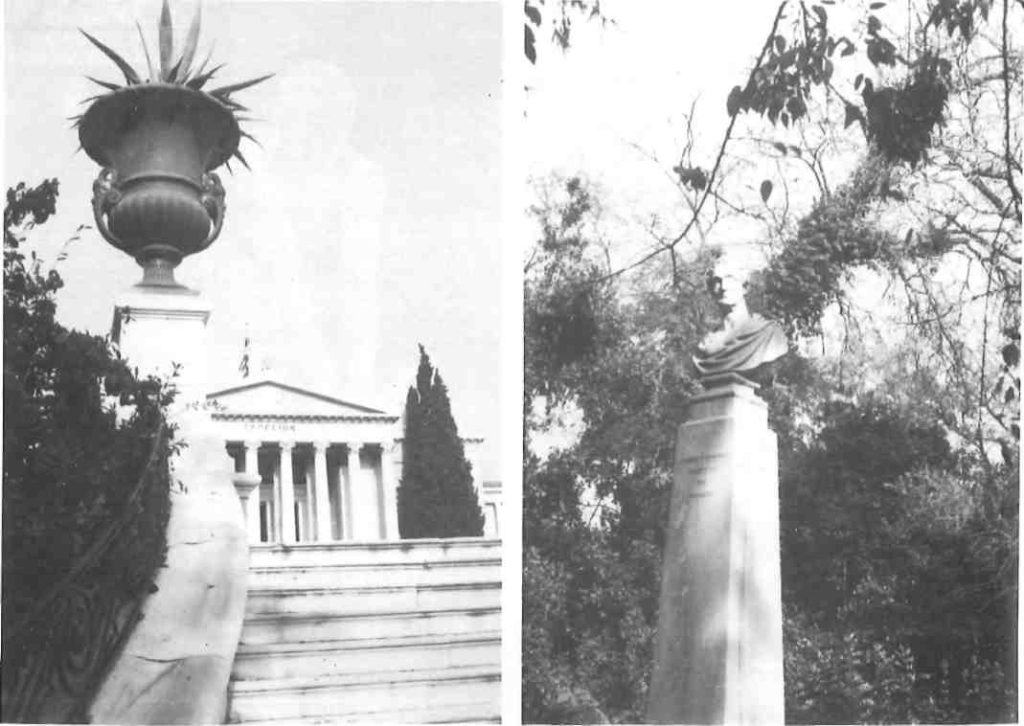

After the jungle-like lushness of the National Gardens, the Zappeion Gar-den just next door is more like a land-scaped promenade. This accounts for its popularity: a place to meet and be seen, not to get lost in. Named after founders Evanghelos and Constantine Zappas, cousins from Epirus who made a fortune in Romania, the Zappeion exhibition hall with its gardens were redesigned by Theophil Hansen from the plans of Boulanger which proved too pricey, The gardens cover an area of 130,000 square metres, on whose grounds the Aigli was long the most popular cafe-dangant in town. Planting began in 1887 when the building was almost complete. On the eve of its inauguration by George I it was suddenly realized that the landscaping had been mostly forgotten. So, planterers were brought in the day before and overnight the wasteland was turned into a mini-Versailles, what a newspaper then dubbed “Le Jardin a la Minute”. Many readers today will nostalgically remember Syngros Avenue miraculously transformed in a similar way in 1980 when the Zappeion witnessed Greece’s formal entry into the EC.

Gangs of gypsies worked ail night planting palm trees to please the signa-tories as they sped up the avenue in their limousines from the airport.

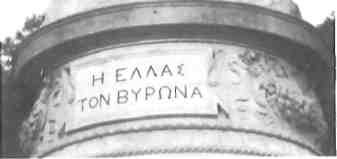

Access to the garden was originally only from Leoforos Olgas in front. The central promenade across was not cut through until 1908. The main features of this somewhat run-down park are the large fountain in front of the build-ing, a marble statue of Pan to the left of the entrance, a 19th-century group sculpture of Byron supported by the figure Hellas at the corner of Leoforos Amalias, and an unusually good bust of Ioannis Varvakis, founder of the famous Varvakeion Lycee, by Leonidas Drossis. There is also a fairly imaginative children’s playground, which Georgie awarded an 8 out of 10. Today, the park is still the traditional place where Athenians parade their children in fancy dress during carnival.

If the atmosphere of the National Gardens is that of a forest, Athens’ other large traditional park, Pedion tou Areos (literally the ‘Field of Mars’) is emphatically urban. The site derives its name from the exercise ground used by the cavalry which occupied it and whose barracks covered the whole area between the Church of the Taxiarchon and Mavro-mataion Street at the time of King Otto. Today, the former cadet school on its edge, Ziller’s handsome neoclas-sical complex, the Evelpidon, has been recently converted into lawcourts. Over a hundred years ago, the open field was used by Athenians for casual recreation. In 1934, it was decided to turn it into a public park, specifically with a view to creating a place where people could stroll, an urbanized prom-enade in the tradition of the village volta. Thus, a symmetrical network of asphalted walkways was laid out.

Today, its leafy paths interspersed with palm trees and small fountains provide a welcome retreat from the hideous bustle of Leoforos Alexandras and Patission Street. It is also an open-air meeting ground for tavli players. Two impressive monuments guard the Alexandras entrance: a huge equestrian of Constantine I on horseback, and a moving marble war memorial depicting Athena Promachos, erected in 1952 “to the memory of the soldiers of Britain, Australia and New Zealand who fought for the liberty of Greece.” One of the main avenues of the park is flanked by busts of heroes and martyrs of the 1821 Revolution. The Church of the Taxiarchon itself is well worth a visit. The oldest of all memorials of modern Athens, it commemorated the Fall of the Sacred Band, a group of untrained Greek-Romanian patriotic students who were killed in a Turkish ambush in June, 1821. The park also boasts a small open-air theatre and its own chapel. Georgie gave the rather smelly duck pond and playground, which has definitely seen better days, a 6 out of 10.

From the Pedion tou Areos, it is just a stone’s throw or a stroller’s brief climb, across Alexandras up to Strefi Hill, a smaller brother protuberance of looming Lycabettus, and another traditional Athenian recreation area. Named after the family who once owned it, Lofos Strefi worked as a marble quarry many years before being planted with pine trees in 1911, thus giving it its jagged, dramatic look. In 1938, it was acquired by the municipality of Athens, and made into a public park. Since that time, stylish blocks of flats have crept towards the top of the hill, but it is still a pleasant place for a stroll along the recently repaved path-ways and a drink at one of the two open air cafes. The hill also affords an excellent alternative view of Lycabettus and the Acropolis which miraculously manages to exclude all the concrete in between. Amazing, too, is the fact that despite the proximity to two of Athens busiest roads, there is no noise of traffic whatsoever. There are a few swings and climbing frames for children, but no proper playground.

At the other, southeastern side of the city’s centre Alsos Pangratiou is situated at the intersection between Spyrou Mercouri and Eftychidou. It was first planted with pine trees in 1908, under the auspices, of Queen Sophia. In 1938, the 30,000 square-metre area became a public park. Other trees and shrubs were planted and a small zoo was established. However, during the Occupation, German soldiers were billeted to the park, with the result that the animals were destroyed and many of the plants and trees cut down. After the war, the municipality of Athens undertook to relandscape the decimated park, creat-ing asphalt walkways, little squares and steps up the hillside behind. Nowadays, the Alsos is a haven both for Pangrati dwellers and, strangely, for throngs of migratory birds that choose to make a temporary home here in the tall pine trees every winter. There is a decent children’s playground, scoring an 8 on Georgie’s scale.

Perhaps the biggest surprise in our park hunting lay just around the corner from Pangrati’s central park. A few hundred metres away along Archimidou Street, just off Plateia Plastira, we ventured through the rather official looking back entrance to the old Olympic Stadium to find ourselves on what must have been the artificial embankment constructed in 330 BC to join the two hills which formed the natural valley in which the original stadium was built. A gravel track running behind the top tier of marble seats is an inner city jogger’s paradise, and more hardy ones may venture up the network of pathways on the western hill. In among the olive and pine trees, there are plenty of wrought-iron benches for non-joggers from which to admire what must be the ultimate view of Zappeion, the National Gardens, the Temple of Olympian Zeus and the Acropolis. Further adding to the atmosphere of Athens of long ago there are also some fenced-off ruins, including the tomb of a ‘Marathonian hero’.

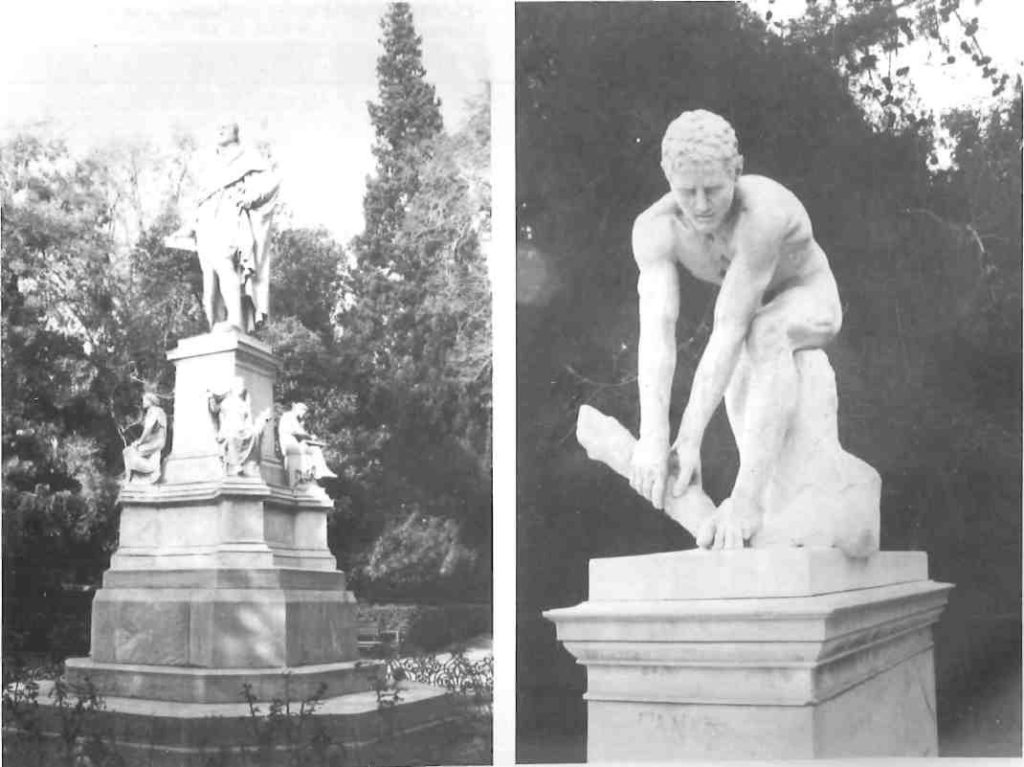

(Right) Dimitrios Filippotis’ masterpiece “The Woodcutter” (1872) suffered castration by vandals a decade ago. He stands at an entrance to the Zappeion Gardens opposite the Stadium

Though right in the centre of the city, this park has a distinctly rural feel to it, enhanced by the almost total absence (joggers aside) of other visitors. Rumor also has it that a secret tunnel leads from the former Royal Palace emerging somewhere on the hill. No playground here, but Georgie deemed it a great place for a picnic. Another much larger park but also with a less formal atmosphere is Syngrou Park, named, like the hospital beside it as well as the avenue leading to the sea, after the wealthy 19th-century businessman and benefactor, Andreas Syngros. It stretches from Leoforos Oulof Palme in the east almost to Mihalakopoulou in the west. In fact, this park can almost lay legitimate claim to being a dasos (forest), a title often wistfully applied by Athenians to the tiniest patch of green. Here it is possible to wander across pine-clad slopes for some considerable time totally out of view of the concrete jungle. Amid the trees are several chidren’s playgrounds of the modern robust wooden variety. Now far away, the recently relandscaped Skopeftirio (shooting range) park in Kaisariani also offers sturdy and interesting wooden play facilities beneath tall pine trees, which Georgie gives a 9 out of 10. He also enjoyed the well-tended grassy areas here, and the marble fountain, a gathering place for local yiayiades. The upper part of the park is still being landscaped, leaving intact the wall against which hundreds of Greeks were executed by the Nazis on May 1, 1944.

For a really good romp, though, Georgie reckons you can’t beat the German-designed and built adventure playground in Plateia Metaxa, Glyfada, which offers a variety of facilities for the young and the young at heart. These include wooden houses or stilts for very little ones, intricate rope climbing frames, a pre-war British army truck and steamroller converted for play, tire swings and a roller-skating cum skate boarding arena. There’s plenty of grass too (by Greek standards), and a refreshment kiosk.

(Left) The Zappeion Exhibition

(Right) Kossos’ bust of the Geneva banker Jean-Gabriel Eynard, the great Swiss philhellene is in the National Gardens

The Byron Monument at the corner of the Zappeion Gardens designed by Chapu and executed by Falcuiere

The statue of benefactor Evanghelos Zappas by loannis Kossos stands beside the portico of the Exhibition Hall he donated to the city of Athens

So if you seek some peace and quiet, a bit of greenery or a place to let the children loose this winter, it is not an absolute necessity to join the Friday evening exodus to the exochi. Athens still has her secrets, some of which remain remarkably undiscovered and ever-green.