It was the summer of 1949. The eight-year-old boy found himself being herded across the Greek-Albanian borders along with hundreds of other children, as the remnants of the defeated Greek communist armies in the civil war fled behind the Iron Curtain. His younger sister, only six months old at the time, died in his arms.

Young Sotiris Fotopoulos was soon sent on from Albania to Romania, ending up as one of the exiled members of the Greek community there. Ultimately, Fotopoulos was to become today’s President of the Union of Greeks of Romania, thereby following in the tradition of a community that has played a key role in the progress of this Central European nation.

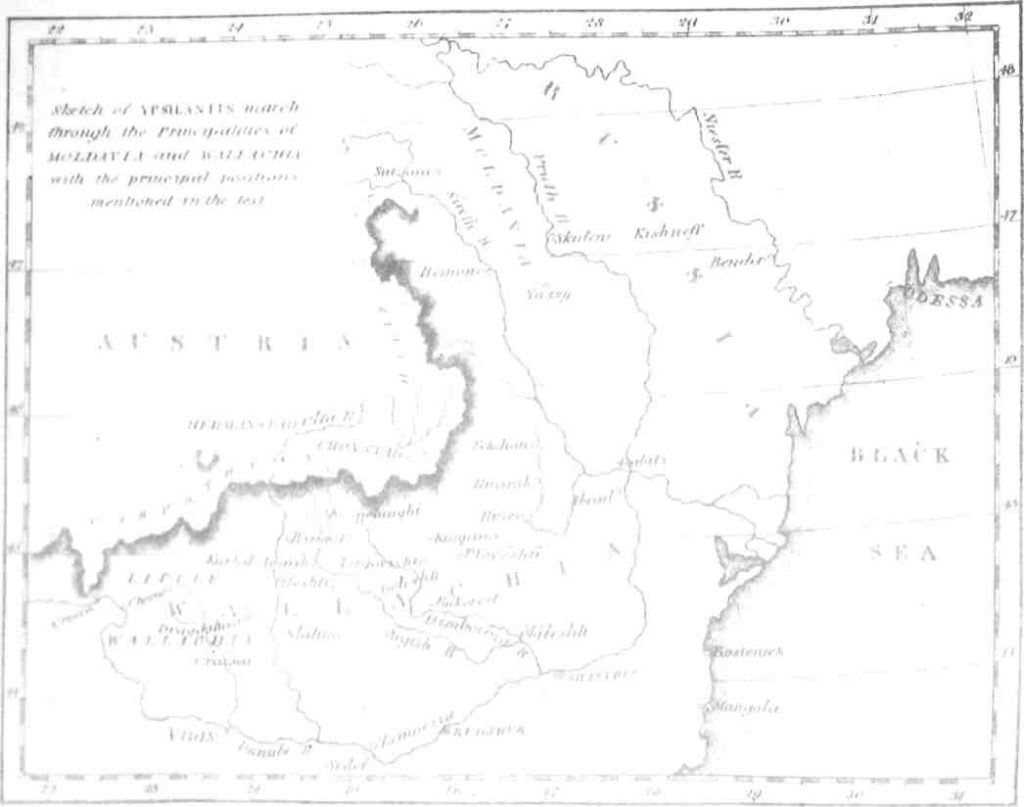

The story of the Greeks of Romania is a long and turbulent one. It can be traced back to the Byzantine period in the tenth century, a time when the Greek and Romanian peoples already shared a common connection with the Orthodox Church. From 1700 until the War of Independence almost all the hospodars of the semi-autonomous principates of Wallaehia and Moldavia were Phanariot Greeks chosen by the Porte (at a hefty price).

Soon, commercial activity was to become the strongest feature of the Greeks of the region, especially round the Black Sea. A strong and prosperous Greek community developed, one that grew steadily up through the 19th century. Greek-led trade became so strong as to develop into a primary force of economic development in Romania. Inevitably, the elite of the Greek community also came to distinguish itself in shipping, banking, education, the arts and, ultimately, even in local politics, Indeed, Apostolus Arsakis became the foreign minister of Romania in 1860. The eminent ‘Arsakeion’ School in Athens is named after him.

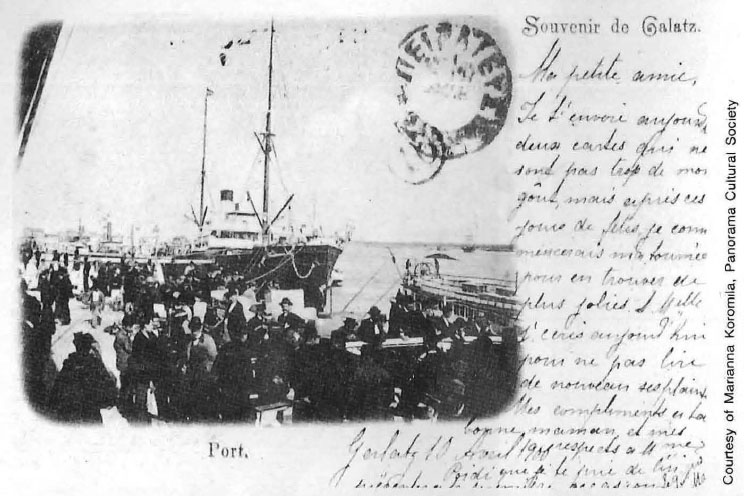

The largest Greek communities were concentrated in what is now known as the Black Sea resort city of Constanza (Tomis at the time), while nearby Tulca and Sulina were almost exclusively Greek speaking. Farther up the river, Braila and Galatzi were centers of the Greek controlled Danube trade. On the Black Sea, at the estuary of the Danube, Sulina was a free port zone widely used by Greek shipping fleets. In Bucharest, there was a flourishing Greek business community which controlled major companies, banks and hotels. Even for today’s visitor the Athena Palace Hotel continues to function as a reminder of this once prosperous, Hellene-oriented period.

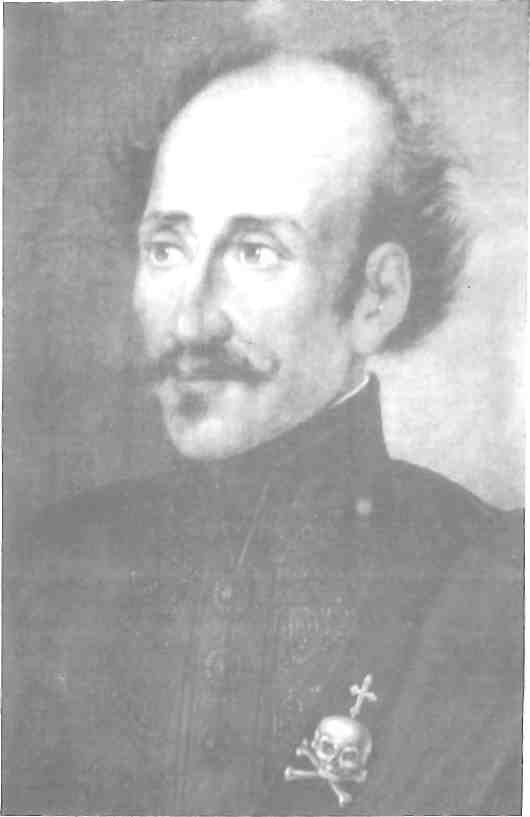

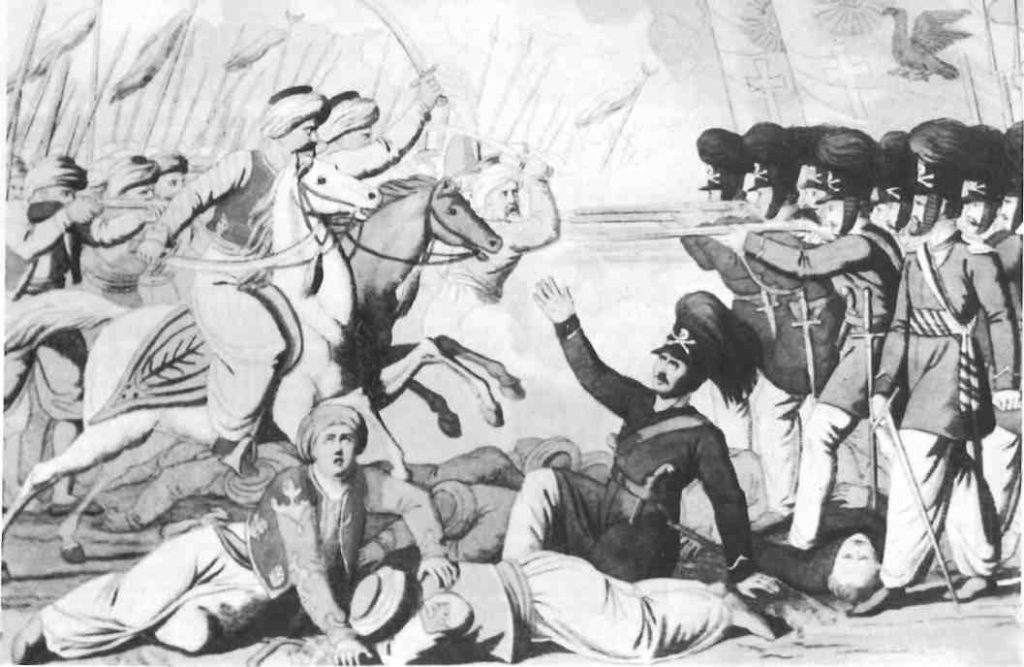

Phanariot Alexander Hypsilantis led the Greek campaign in Romania. He was betrayed by the Tsar, imprisoned by the Austrians and died in 1828

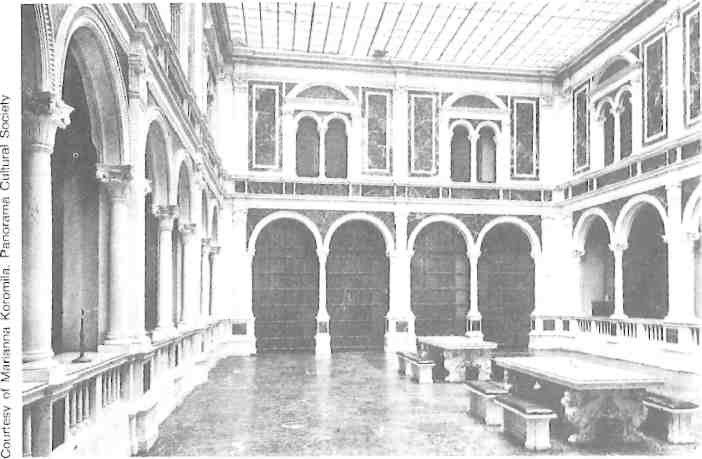

Hospotar Michael Soutsos was painted by Louis Dupre just before Hypsilantis’ invasion. He was the last Greek prince of Moldavia

Business merely constituted the foundation of the Greek communities influence. Coupled with the magic aura surrounding ancient Greek civilization, it soon played a major role in the country’s academic life. One of the first academies was established in Bucharest with major Greek participation. In schools and universities, the study of modern and ancient Greek came second only to French. Even today the older generation of academics has a working knowledge of ancient Greek. The Greeks built not only schools but also churches and villas that can still be seen today. Each Greek community had its own churches and schools, facilitating the development of an environment in which the Orthodox Church flourished.

Until World War II, Romanian-Greek relations were harmonious. However, the situation quickly de-generated with the imposition of communist rule in 1948. At that time all foreign communities were broken up. Properties were claimed by the state; churches, schools and cultural centers appropriated. Those who refused to submit to the demands of the new regime, those who insisted upon declaring themselves Greeks, were forced to leave Romania empty-handed. By 1953 100,000 Greeks had chosen exile or emigration. Many at first returned to Greece if they could – not if they were communists with a specific criminal record. Many others fled to Germany, England, Canada and the United States.

“Organized Hellenism was virtually wiped out,” says Fotopoulos. “The Greek Lycee was the only remaining institution until 1974 when it, too, closed down. Most of its students were those children brought over from Greece in 1949 by the communists. Some 3500 Greek children were settled in Romania at the end of the 1945-49 civil war, most of them aged six months to ten years old. This was one of the most bitterly contested consequences of the civil war.

Communists claimed that the children were taken out of Greece to the neighboring countries behind the Iron Curtain to avoid bombardment by the American-backed Nationalist army. The nationalists argue that it was paidomazoma, the rounding-up of children to be brainwashed and trained as the nucleus of a future communist militant force. Children, like Sotiris Fotopoulos, had in fact fallen victims to something equivalent to kidnapping by communist bandits, much as the Ottomans had found recruits for the Janissaries

The truth of the matter is that many of these children, who in the overwhelming number of cases were not accompanied by their parents, died either from malnutrition or the harsh winter conditions. The ones who crossed into Albania and then moved on to Romania were not the only ones. More than 100,000 Greek partisans and their families were dispersed throughout Eastern Europe, the largest grouping settling around Tashkent in the Soviet Union.

In Romania, kindergartens and elementary schools were arranged for the Greek children in the 15 largest Greek communities already existing in the country. For many of the children, including young Sotiris, it would constitute their first school. Not surprisingly, they were taught Romanian. It became their first language. Unlike Sotiris, many became totally ‘de-hellenized’.

From 1948 to Ceausescu’s overthrow in 1989, most Greeks were only allowed to study Romanian. Consequently, it became their ‘mother’ tongue. “All foreigners in Romania supposedly had equal rights and obligations, but the Greeks felt more pressure because their homeland was a capitalist country,” says Fotopoulos.

These fears were heightened by the suppression of the Greek churches which had been the most prominent outward symbol of Hellenic identity. The only church which remained in Greek control was Aghios Dimitrios in Bucharest, and this solely because it was located on the grounds of the Greek Embassy.

One week after the anti-communist uprising and the execution of Ceausescu, Fotopoulos sought constitutional approval for the formation of the Uniunea Elena Din Romania, meaning ‘Union of the Greeks of Romania’. Approval was granted, symbolizing the beginning of a “Hellenic revival”.

Another landmark was the decision to participate, as a national community, in the parliamentary elections in September 1992 in pursuit of the one seat in Parliament allowed by the Constitution for foreign communities. This target was also achieved. 3500 Greeks are now registered in the Union, even though it is estimated that there exist about 30,000 Romanians of Greek origin. Fotopoulos was elected parliamentary representative, but he opted to remain President of the Union and passed his parliamentary seat to a colleague.

The Charter of the Union declares its goal to be the protection of the cultural interests of the Greek community, the “strengthening of the traditional Greek-Romanian relations of friendship”, and to help to “achieve Romania’s inclusion in the European Community and a united Europe.”

Says Fotopoulos: “This is only the beginning. We hope to become the bridge between Greece and Romania that will serve as a model for the entire Balkans.”