The tourist explosion based on charter flight holidaymaking in western Crete in the last decade is significantly prolonging the life of the traditional Cretan leather industry. Custom-made boots and shoes and handmade sandals, bags and belts from vaketta (treated leather), tanned with natural, environment-friendly products are now being carried or walked on throughout the world by customers who have patronized of Chania’s Carnaby Street – Stivanadika, or Leather Lane.

craft.

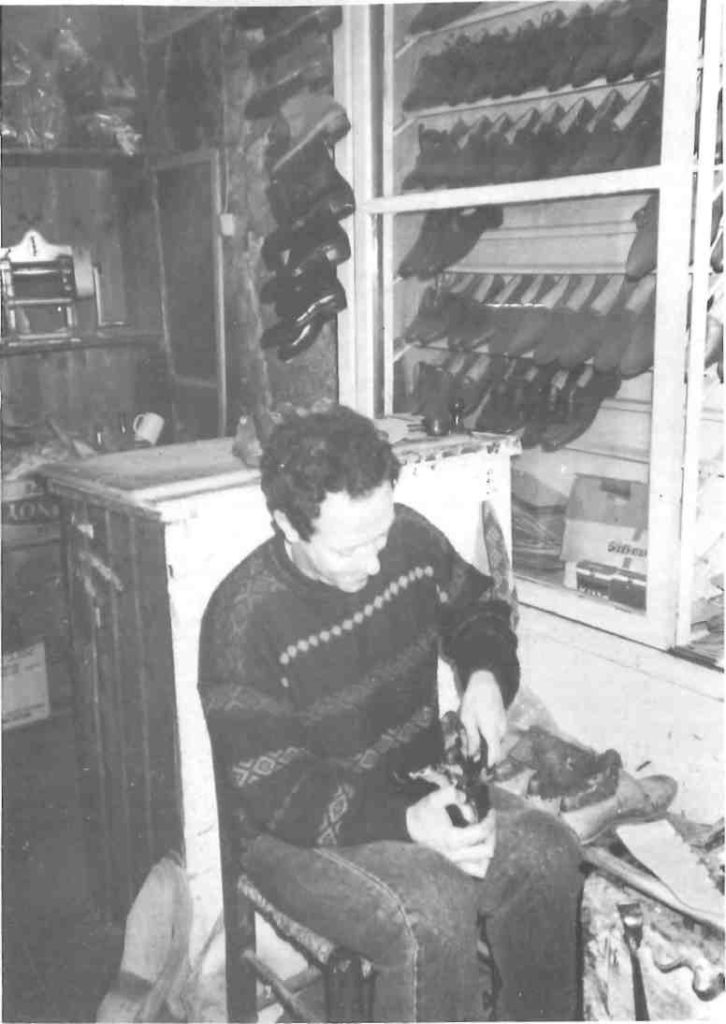

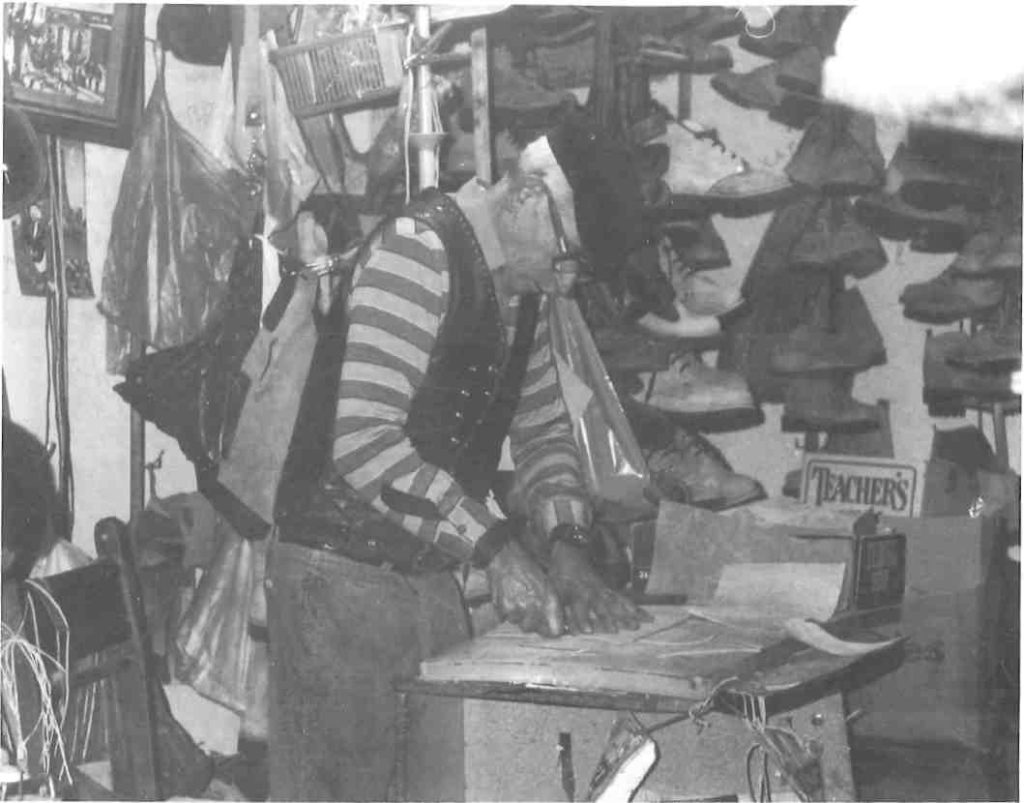

“European women love my Cleopatra sandals,” says extrovert Lefteris Pirpinakis, a master craftsman married to a Frenchwoman. Enjoying the stimulation of summer visitor traffic, he no longer has to burn the midnight oil as he did when an apprentice, sometimes working till dawn to finish orders on time. He produces stylish boots for women, working and riding boots, made-to-measure in a week. The dethroned (but still well-shod) king of Greece is among his customers.

Doyen of the remaining master craftsmen, Herakles Koubaritakis, over half a century in the trade, agrees tourism benefits the traditional Cretan craftsmen. “We make a lot from tourists,” he says.

But only half a dozen still ply the trade of tsagaris (Cretan maker of boots) in Stivanadika, officially called Skridov, after the Russian admiral whose fleet in Souda Bay at the turn of the ι century assured freedom after the Turks left in 1898. Ranks have been quickly decimated since the 1960s when 50 or more still hammered away.

The street’s oldest mastoras, 70-year-old Ioannis Markoulakis, began learning his skills 55 years ago. Working without a pause at his marble work-bench cutting vaketta to size for his apprentice to make up, Markoulakis relates how the old craftsmen tyrannized apprentices, begrudging them money and even training. “They tried to keep the trade secret, afraid you’d steal bread from their mouths,” he says.

Xenophon Kourkoutakis also learnt the craft during the war years. “Our generation took to the trade to feed itself,” he says. “We made boots and shoes for the German military during the Occupation and women’s shoes and sheepskin boots which were sent to Germany.”

He takes four hours to make a pair of shoes – “And I don’t work lazily” – selling them for 10,000 drachmas. “But factory-made imported shoes may be less than half that price.”

The handmade stivania (work boots), ipodimata (special occasion boots, perhaps patent or white leather) and shoes from Stivanadika have become luxuries often beyond the means of Cretans. Many of them opt for imported footwear from Taiwan or Brazil.

Shepherds and olive growers now tend to prefer cheap, light, imported rubber boots rather than the traditional high, snug-fitting heavy leather ones. Gone are the pre-war days when truck-load of handmade boots and shoes left Chania for the rest of Crete.

The trade began to shrink in the hard post-war years when many Chaniots emigrated to America and Australia. Skills are generally being learnt now only by sons working with fathers, like Dimitrios Kourkoutakis, or Gabriel Katsoulakis who has settled in beside his father after studying marketing in Larissa.

“Young people now go to college and become doctors, lawyers and engineers. They don’t want to sit eight hours a day in one place bootmaking,” says Katsoulakis.

A young Syrian has worked with Markoulakis for several years and an electronics engineering lecturer at Chania Polytechnic has learnt to make up footwear to Pirpinakis’ designs.

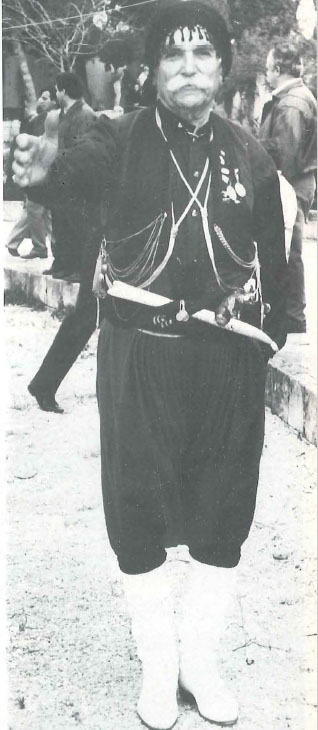

The mastores are proud men. They see themselves as the elite of craftsmen, fancying they enjoy a charisma not the privilege of the woodcraftsmen, bellmakers or knifemakers down the road.

“The Turks respected the tsagares as pallikaria – brave and noble – and did not venture into Stivanadika,” says Markoulakis, relaying on lore learnt from his grandfather.

Equal opportunity for women, it should be said, has not arrived in Stivanadika: the only woman working with leather in the street is a cheery machinist stitching uppers in the Markoulakis workshop.

The men-only craft survives because its wares are favored by visiting foreigners who see it a rare bargain to buy at 20,000 drachmas ipodimata from the leather of their choice, made in a week by an old-fashioned craftsman.

But Chaniot shoemaking talent is not confined to Stivanadika. Mass production began in the 1960s at the Karaids factory, whose distinctively styled footwear, says Koubaritakis, has won prizes at international exhibitions in Paris, Bonn and New York.

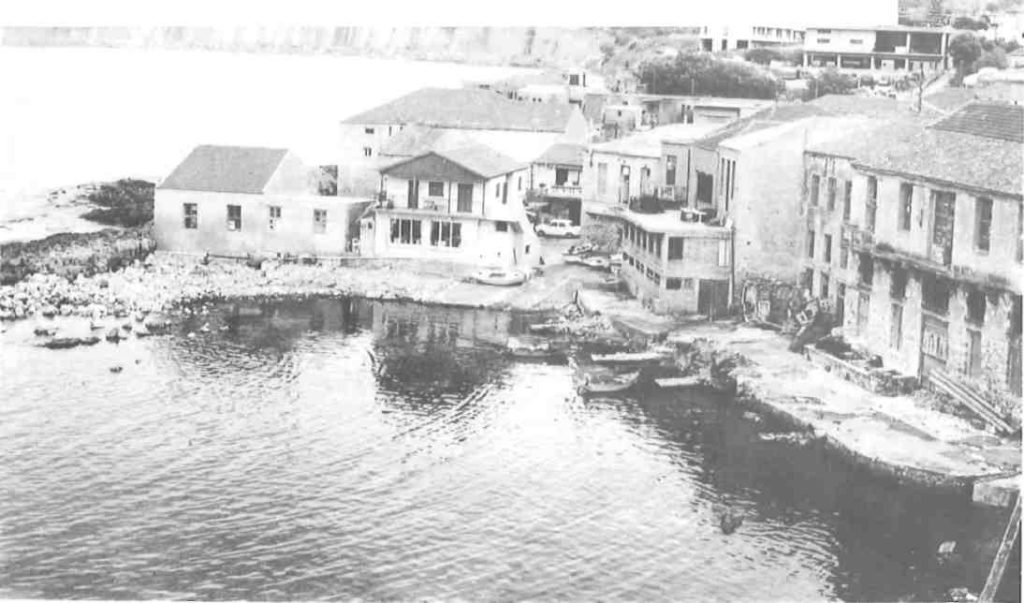

Chania’s seaside vyrsodepsies (tanneries), established along the shore at Halepa just east of town towards the end of Turkish rule, supply craftspeople in Chania, Athens and elsewhere in Greece with vaketta and soloderma (sole leather), and factories, too, with the latter.

“Ten years ago there were 40 tanneries. Now there are 25. I expect the same rate of closures in the next decade,” says George Kalliyiannis, one of the two agents in Chania handling 90 percent of hide imports. “Great trade losses are occurring because of increased production from fully mechanized modern tanneries supplying leather craftspeople and shoe, boot, bag and belt-makers.”

But loyal tsagares staunchly maintain the tanneries produce the best leather in the world. Says Koubaritakis: “It is soft, supple and easy to use.” Some claim it is the purity of the local spring water that gives such happy results.

Kalliyiannis says the tanneries get through astonishing amounts of work. “There’s big production; it is a lively scene. Last year I sold 24 containers of hides, 240 tons.” The suspension-dried calf hides come from all over Africa: Kenya, Uganda, Sudan, Abyssinia, Malawi, Madagascar. Hides before the war came from Europe, mainly Poland and France, supplementing Cretan wild goat and sheepskins.

He also supplies valonia powder, Argentinian quebracho (from tree bark), South African mimosa and German fish oils used in the later stage of tanning. He continues his father’s shoemaker supply business too.

The coast near Chania provided ideal conditions for 19th-century tanneries: shallow sea on rocky shores, so raw hides could be hung in the waves for cleaning and softening, with plentiful fresh-water springs close by the water’s edge.

The picturesque tanneries at the foot of Vivilaki and Aghias Kyriakis streets in Halepa are built just over the rocks, with wells sunk to minimize effort in washing and rinsing. Similar conditions existed in Rethymnon where Greek tanneries developed west of the town and Turkish ones far to the east, says 89-year-old Rethymniot Polychronos Vernidakis.

On Samos, too, in Turkish hands till 1912, the reputedly biggest tanneries in the Ottoman Empire flourished in Karlovasi. The extensive old tannery buildings there remain today as deserted ruins according to a Chania resident given a guided tour 20 years ago during the Junta period by the island’s most distinguished exile, the late poet Yiannis Ritsos.

The simple tanning technique still used in Chania was learnt from Syrians during the Egyptian suzerainty over Crete which lasted from 1832 till 1840. They were sent to establish the industry in order to satisfy the demands of the Egyptian market, says Chaniot industrial archaeologist Stavroula Markoulaki. Her source is a brief account of Chania by K.G. Fournarakis written in 1928.

The characteristic local leather color comes from the velanidi, the acorn produced by the valonia oak which grows prolifically round Rethymnon. The tree is now a protected species. Its survival is threatened, according to Rethymniot historian Dr Nikolaos Kokonas, through illegal night felling by developers clearing land to build.

Oldtime tanners scrubbed the hides on wooden boards in stone troughs out into the natural rock floors. Tanner Manolis Voutetakis recalls cleaning 40 skins a day. “Sometimes the water froze in the troughs in winter,” he says.

When hides were left overnight in the sea, tanners slept nearby with their ears cocked for a change in weather, ready to leap to the rescue before waves washed them away. “The work was very, very hard and heavy,” he recalls. Electrically powered rotating Swedish timber barrels now treat 100 skins a day.

Voutetakis works with his son, Antonis, and an occasional shortterm foreign laborer. He looks ahead to 10 more years before retiring on a pension.

A tour of his tannery begins on the rocky floor where dried hides soak for four days in seawater. They are then revolved for eight hours in barrels of water to get rid of mud, dirt and vestiges of meat.

In all tanneries an essential sector of the workforce is a team of sleepily well-fed cats lazing round, bouncers so to speak to deal with rats and mice scurrying after morsels of African dried veal on the untreated hides.

In the depilatory process, after being cut in half, hides are immersed for two days in a solution containing lime and other chemicals, then rinsed to get rid of all traces of them. “The water from the final rinse has to be clean enough to drink,” says Voutetakis.

The central procedure in the tanning process is the immersion of skins for three to four hours in the dark solution containing velonia, quebracho and mimosa.

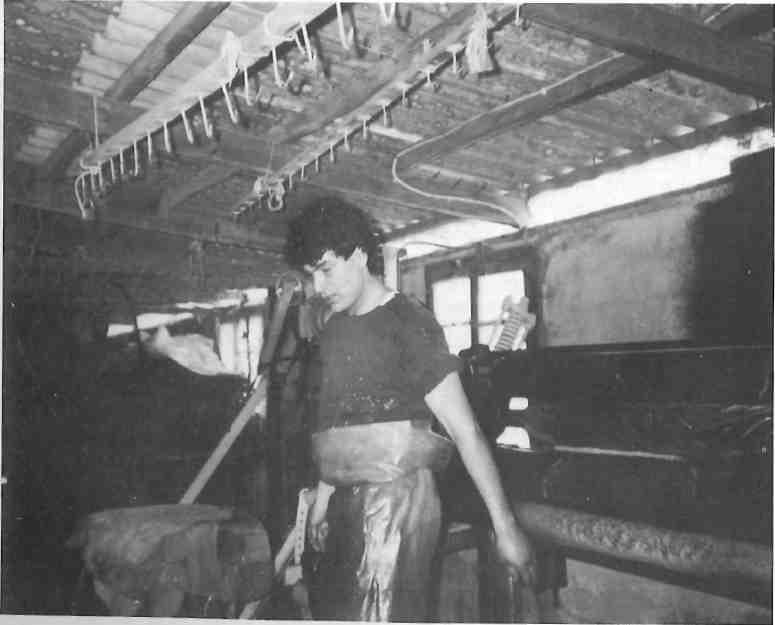

After topping and tailing to achieve even thickness, skins go by open lifts to the upper floor for treatment with oils and stretching and flattening for a final trim before being hung – or perhaps laid out on the road in the sun – to dry. A bit further along the coast in Aghia Kyriaki, Manolis Androulakis, 60, also remembers the hard old days scrubbing by hand. He demonstrates the former arduous methods of flattening and scraping with a hand-held tool, before hydraulic fleshing machines were introduced, and polishing the dried tanned skins with a cork implement. In his estimate, a good strong worker could get through 60 to 70 hides a day. “The machine does 500, more if necessary, without getting tired,” he says.

At the other end of the string of tanneries an older tradesman, 80-year-old Giorgos Voyiatsakis, who began working in 1927, continues in partnership with his son, Vangelis, supplying footwear manufacturers round Greece.

Business for the tanneries depends on the EC, he says, admitting “the rest of Europe has more resources and better automation and computerization.” The old man gives the glimmer of a smile at the mention of computers in his archaic surroundings, the old sea-washed tannery on the rocks facing east to the chapel of Aghia Kyriaki, which overlooks a tiny inlet with a few caiques and the stony remains of a Venetian monastery destroyed, according to that excellent guidebook by Stergios Spanakis, and its saintly inhabitants massacred by pirates in the 16th century. But the tanneries still exert appeal for practitioners; Yiorgos Voutetakis resumed his father’s trade in Aghia Kyriaki in 1973 after 12 years sampling life down under, working in a General Motors foundry in Melbourne.

“The lifestyle here is healthier. We’re all good strong men.” He produces sole leather and supplies for Athenian saddlers. A son, Michalis, is learning the trade, as well as another apprentice, Nikos Nikolakakis.

But tannery days are numbered on prime coastal property along the Cretan Sea. The land is to be appropriated for hotel and recreational development. Like the Rethymnon tanneries, Chania’s are to be relocated inland in an industrial district where the dark brown effluent will not pollute bathing waters.

The Greek Ministry of Planning is scrutinizing proposals. “Opinions differ on the desirability of preserving the tannery buildings,” says Stavroula Markoulaki. “Already one has been bought by a developer said to be putting up a hotel. The fear is that once hotel development has begun it will be hard to stop.”

As a gesture of respect for the historic local industry, the Historic , Folkloric and Archaeological Society of Crete in cooperation with the Tanners’ Union brought out a handsome big calendar this year depicting tannery scenes. Markoulaki wrote the text, Discussion has begun on the possibility of preserving one of the tanneries as a museum. Foreign archaeologists living in Chania support the proposal.

Meantime it is business as usual for the score or so tanneries that survive, because not only Chania’s Stivanadika but in the maze of Monastiraki and Plaka tourist shops in Athens, top sandalmakers swear by the product.

“Of course it’s the best,” says Stavros Melissinos. Day in, day out, year round, Athens’ famous poet-sandal-maker works at his bench on Chaniot vaketta. The sandals he makes become like second skins, as much part of Greek summer as ouzo and octopus and Aegean sunlight.