After many millennia of relatively harmonious co-existence with man, the Brown Bear, Ursus Arctos, has over the last few centuries gradually been brought to the verge of extinction in Western Europe, a victim of modern man’s ever-increasing demands on the earth’s resources. There now remain only very small populations in Spain, France and Italy. In Greece there is said to be between 60 and 120 (an exact figure is impossible to determine), the most southern dwelling bears in Europe. Numbers have continued to dwindle in recent years, however, despite the status of the bear as a protected animal declared in the Treaty of Berne and ratified by Greece in 1983. The implementation of legislative decree 86/69 forbids the hunting, transportation, public exhibition and mistreatment of bears, and gypsies with tamborines leading bears on chains are no longer sights to be seen.

Now it is hoped that the project recently completed by the World Wide Fund for Nature entitled ‘Conservation Strategy for the Brown Bear in Northeast Pindus’ will lead the way towards redressing the environmental balance between man and the Brown Bear.

Most of the following information was given to me by the project’s biologist, Penelope Matsoukas.

The Brown Bear is the largest indigenous animal left in the European wilds. It has a maximum length of 1.7 to 2.2 metres and a weight of 100-340 kilograms, though the newly born cub weighs only 350 grams. It is surely one of the most beautiful, too – a fact recognized and recorded by the ancients in the myth which tells of the lovely nymph Callisto seduced by Zeus and turned into a bear by jealous Hera. She might have been hunted to death, but Zeus plucked her up into heaven and set her among the stars, where she still remains today as Ursa Major, the Great Bear.

Brown Bears have a very highly developed sense of smell and hearing, but their sight is only so-so.

They are fast runners and may cover up to 20 kilometres a day. With an almost exclusively vegetarian diet of nuts, fruits, acorns, maize, wheat, shoots and leaves, European Brown Bears only very rarely resort to eating flesh. Their preferred habitat is mixed forest, where their food is found in greater abundance. They mate in the spring, and the females bear two or three cubs every two years, amounting to 20 or 30 cubs in a lifetime of approximately 30 years. The adult males almost always live alone, except during the mating season.

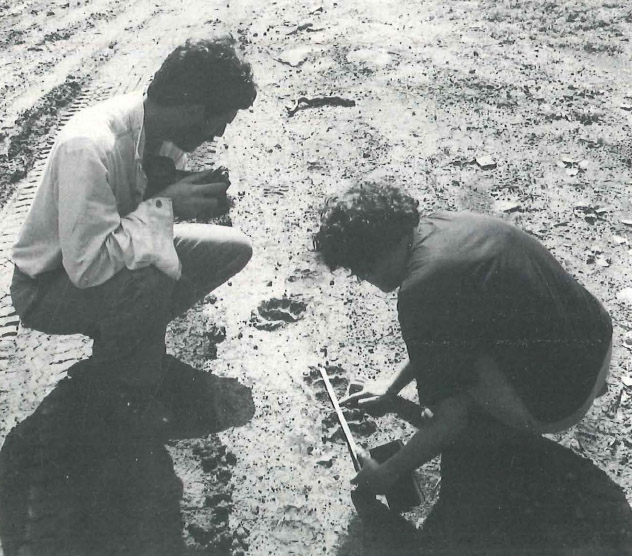

Bears in Greece are found in four separate areas: the Pindus Mountains, the Peristeri range that rises above the Prespa lakes, and the Rodopi and Vrondous mountain chains lying along the Bulgarian border. The WWF program, which was conducted between early 1990 and 1992, covered a 1000-square kilometre area in the North Pindus, and set out to explore the nature of the relationship between man and bear in an area where there is considerable human activity. It was the first and only systematic study so far on this matter.

Close monitoring of the space used by the bears enabled the WWF to identify the main threats posed to their existence by their proximity to 20th-century man. One of the most significant findings of the survey was that in areas where the land is farmed, such as around Grevena, bears may rely on cultivated food (wheat, fruit, grapes etc.) for as much as 28 percent of their diet, causing a certain amount of damage, though exactly how much is sometimes exaggerated by the farmers. Beekeepers, too, have reasons to be wary of bears, and the WWF has funded the construction of a solar-powered electrified anti-predator fence around the region’s largest apiary. However, despite the existence since 1990 of a law entitling shepherds and beekeepers to compensation for damage cause by wild animals, no one has as yet received one drachma for damage caused by a bear.

Thus, although hunting has been officially outlawed, it is perhaps not too surprising that outraged farmers choose to take the law into their own hands from time to time. Leisure activities such as hunting and off-road car and motorcycle races were also found to pose a serious threat to the bears’ existence. The WWF made contact with a local motocyclists’ group , proposing that races should be held away from areas having seasonal importance for the bears. Two races were organized on the basis of maps provided by the WWF project. They have gained the support of hunters, who even helped to finance the publication of a book on the ecology and conservation of the bear. Developing public awareness of the plight of the bear was a priority of the WWF project: public presentations, conferences and seminars were held in the area, and numerous articles were written in local newspapers. The local population was generally very supportive of the project, and have expressed outrage at the rare incidents of bear shooting.

Another major threat to the bear, the WWF found, is the changing face of the landscape: oak forests have been over-exploited for firewood; the bear zones have become increasingly fragmented as more and more cereal fields are opened up. The WWF held contacts with the forestry services and undertook the training of four local forestry technicians as part-time researchers and surveyors with a view to furthering local awareness. Given the areas needed by the bears, the small existing protected zones, such as the Pindus National Park are not enough. A population of a dozen or so bears was estimated to live on the 1000 square kilometre study area. With a surface of only 34 square kilometres, the Pindus National Park cannot guarantee the survival of even a single Brown bear.

The WWF project concluded that, with the cooperation of local people, allkinds of activities should be readjusted over the whole of the Pindus region. It is to be hoped that similar and larger scale projects will be funded in the future to help achieve this goal. Otherwise, at least one of the Greek bear’s last stands may fall.